Violence in Bangladesh’s RMG sector: Disposable lives, dispensable labour

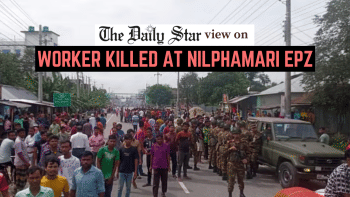

On September 1, at the Uttara Export Processing Zone (EPZ) in Nilphamari, 20-year-old RMG worker Habibur Rahman was shot dead when police and army personnel opened fire on a demonstration against layoffs and the sudden closure of the Evergreen Products Factory (BD) Ltd. Habib, a night-shift operator at Eque International and a resident of Kazirhat village in Shongalshi union under Nilphamari Sadar upazila, was killed while leaving the EPZ after his shift, according to Prothom Alo. At least 10 others were grievously wounded as law enforcers attacked workers demanding their due rights.

It is a bitter irony that in the post-uprising Bangladesh, a nation quite literally built upon the blood and courage of the working class, it is their bodies that are once again being sacrificed, with Habib now the third RMG worker to be shot dead since the much-heralded dawn of "New Bangladesh." Kawser Hossain Khan was gunned down in Ashulia in September 2024 by law enforcers who opened fire on workers demanding their rights, while Champa Khatun succumbed in October to injuries sustained during clashes over unpaid wages.

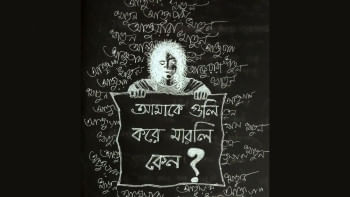

Their bodies join a long procession of the dead: Rasel Howlader, Anjuara Khatun, and Jalal Uddin shot in Gazipur in 2023; Jesmin Begum at Dhaka EPZ in 2021; Sumon Mia in Savar in 2019; Badsha Mia and Ruma Akter in Gazipur in 2013; Tajul Islam, Babul Sheikh, and Shafiqul Islam in Tongi in 2009; and further back still, those who fell during the mass strikes of 2006, and countless others whose names barely make it to the news before fading from memory. They are so insignificant, in fact, that there's no documentation even of the actual number of workers killed in the country over the decades for daring to demand their rights.

Karl Marx's injunction that "capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt" finds tragic clarity here. The garment industry thrives on biopolitical disposability—labour rendered precarious, expendable, even terminal when workers assert their rights. The repression of labour is rationalised as economic stability, and indeed, is necessary to maintain the rates of surplus extraction demanded by buyers like H&M, Zara, and others, who profit while distancing themselves from the violence in the factories. It is no wonder that the powers-that-be inevitably smell plots to destabilise the nation whenever workers mobilise. Habib's death is emblematic of a recurring regime of accumulation sustained by neoliberal governance, in which the industrial police act as the final line of enforcement for the genealogy of capital.

Bangladesh's garment industry is frequently held up as a miracle, cited by the World Bank, the IMF, and the government itself as evidence of the country's integration into the global economy, yet beneath the charts of export earnings and growth rates lies the reality that this "success" is premised on systematic repression and structural violence. The Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS) estimates that the sector employs more than four million workers, of whom around 53 percent are women, often young migrants from rural areas who enter the factories because they are the only source of survival wages in an agrarian economy increasingly destabilised by landlessness, climate shocks, and dispossession. They do backbreaking work—12 hours, sometimes 14, bent over sewing machines, in suffocating heat and air thick with fibre dust—and for what? For wages that remain among the lowest in the world. Even after the most recent "increase," the minimum wage stands at Tk 12,500 (about $103) per month, a figure that does not even begin to cover the cost of rent, food, healthcare, and schooling for a family of four in Dhaka. It is not a living wage in any sense of the word. It is, what you might call, a survival wage, calibrated precisely to keep workers alive enough to return to the factory floor the next day, but never secure enough to stand with dignity or to bargain without fear.

About 10 percent of more than 4,500 garment factories in the country have registered unions. Yet, even this figure risks exaggerating the actual strength of labour, for many of the registered bodies are little more than management-controlled "yellow unions," while only a handful have managed to secure genuine collective bargaining agreements. It is a system carefully designed to preserve the façade of freedom of association while ensuring that workers' power is neutralised. Meanwhile, union registration is routinely delayed or denied, organisers are attacked, harassed, dismissed or blacklisted, and legal harassment wears down those who persist. And when co-option, intimidation, and firings fail to discipline labour, the state does not hesitate to reach for the ultimate weapon: bullets. The lesson is brutal in its clarity: in Bangladesh's garment sector, the very act of organising carries a cost that exceeds lost wages or dismissal, for to stand up is to risk not only your job but your life.

At least 45,000 workers were arrested at different times during the Sheikh Hasina regime. Can you imagine the devastation in their households—families forced to sell off the little they had, to mortgage their futures, to drown in debt simply because a father, mother, son or daughter dared to participate in a wage protest? After relentless advocacy by labour rights groups and unions, many of those cases have finally been dropped. (We won't ask why well-known/convicted extremists/criminals walked free within the first month of the uprising, yet it has taken over a year for innocent workers, jailed only for demanding their due wages, to be released.). But what of the system that criminalised them in the first place? What of the state machinery that treats wage demands as sedition, sees "conspiracy" whenever workers take to the streets, and brands collective action itself as a threat to national stability?

Why was the Industrial Police created in the first place, and why are we not demanding its dismantling? Its own website explains that the force was created in response to repeated "unrest" in the garment sector—protests over the 2006 labour law, demands for unpaid wages and Eid bonuses, factory fires, and what it describes as "sabotage" or "rumour-mongering." It laments how every year around Eid, workers' mobilisations would spill into the streets of Ashulia, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Chattogram, leading to highway blockades, vandalism, and clashes that, in the words of the state, "disrupted production, threatened investors, and undermined a safe investment environment." Owners' associations, foreign buyers, and business leaders demanded a specialised force, and in 2009, then Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina announced the plan in parliament. In October 2010, the Industrial Police was formally launched with units in Dhaka, Gazipur, and Chattogram.

Stripped of its euphemisms, this admission is damning. The Industrial Police was designed specifically to defend capital, ensuring that the logic of accumulation is never interrupted by the demands of those who make accumulation possible. Its very existence lays bare the fusion of industrial capital with political power, for the factory owners in Bangladesh are also often parliamentarians (or friends and family of parliamentarians), ministers, financiers of ruling parties, and architects of state policy. They are, in effect, the state itself, entangled at every level of governance.

When workers are fired upon, it is law and order of capital functioning exactly as intended.

Even as the existing industrial zones remain sites of recurring violence, the state continues to expand the model, announcing new export processing zones (EPZs) as symbols of progress and investment. Yet, union formation remains banned in Bangladesh's EPZs. Despite growing calls from labour groups and mounting international pressure, EPZ workers are still denied the most basic rights that are taken for granted elsewhere. In practice, EPZs carve out pockets where labour law is suspended in the name of attracting foreign capital, offering global buyers and local owners an even cheaper and more disciplined workforce. Critics have long argued that this regime is not about creating decent jobs but about insulating capital from accountability, where profits are secured by enclosing workers in zones in which surveillance is constant, police presence is permanent, and dissent is criminalised at the outset.

The 2024 mass uprising, which many hoped might reconfigure the architecture of power, has done little to alter this. For all the rhetoric of transformation, the structure of the state remains intact, its class character unchanged. Indeed, what has followed has been a more brazen embrace of neoliberal capitalism, celebrated by the new ruling elite as the pathway to national redemption. The same factory owners who enriched themselves through repression now continue to preside over the sector, enjoying impunity for past crimes and protection for the present ones. The same police who once fired on workers under Hasina's rule now fire on workers under a different dispensation, proving that the coercive apparatus does not belong to a party but to capital itself. And the same global brands continue to extract value from the cheapened lives of Bangladeshi workers while carefully disavowing responsibility for the conditions that make their profits possible. The uprising, in other words, did not rupture the order of exploitation but reinscribed it, proving again how flexible capital can be in absorbing crises and renewing its grip.

As long as capital commands the state, and as long as the state secures accumulation through coercion, workers will continue to die, no matter which party is in power. The question has always been: can we imagine and construct politics that refuses disposability altogether—a political system that recognises the sanctity of life and that refuses to subordinate human dignity to the demands of global accumulation? Until we can do so, no matter how many reform proposals we draft and how many press conferences we hold, we will keep adding names to the list of martyrs, each death both an individual tragedy and a collective indictment, each body yet another reminder that under capitalism, workers' blood is the cheapest commodity of all.

Sushmita S Preetha is a writer and activist.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments