A shameless plug for my octogenarian mum

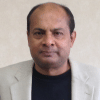

Dr Afzalunnessa, retired professor of anaesthesiology, was conferred an honorary doctorate by the Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University at its third convocation on February 19 in recognition for her four decades of service to anaesthesiology in Bangladesh.

Dr Afzalunnessa is my mother. This an unabashed tribute to a remarkable woman. It also happens to be true. This is a tribute not only to my mother, but to a remarkable generation of women professionals who were pioneers in the formative years of Bangladesh.

Let me begin with an anecdote.

My mother is at work at the operation theatre. It's a serious, difficult case, which is why my mother is there (otherwise junior anaesthetists would be at work.) The patient is a pushcart-puller.

Mum keeps a hawk's eye on the patient's vital signs throughout the operation and waits until the patient regains consciousness. A junior doctor, watching her during the entire operation, can no longer control her curiosity.

"Madam, is the patient some relative of yours?"

"No, not at all," my mother replies, a little surprised.

"Oh, you were so concerned and caring, I had thought he must be someone close."

"That's the nature of our specialty," mum replies. "You always have to be very, very careful, because every life is precious."

That, in a nutshell, was my mum's work ethic.

Life was never a cakewalk for mum, but you'd never guess that from looking at her. During my entire life I've seen her working extraordinarily long hours, multitasking with a skill that would put a juggler to shame, and yet she did it with infectious joie de vivre.

Raised in a family of eight siblings on the meagre pay of a schoolteacher, she has harrowing stories of hardship. By the time she got into medical school, she knew her family could not afford to put her through school. This is where one of this region's most farsighted philanthropists—the deceased jute tycoon Ranada Prasad Saha—came in. This enlightened man provided stipends for female medical students for the entire duration of their education. Quite frankly, my mother would not have been able to finish medical education without that support. I'm proud of my mum for many reasons, but I'm probably the proudest of the fact that she publicly acknowledges her debt to RP Saha with great respect and affection.

Graduation brought a new set of challenges. My parents married, but jobs were non-existent. So, my father (late Dr Badrul Alam, later a renowned paediatrician) got a job at Khyber Medical College in Peshawar, Pakistan. My mum followed, and soon got a job at an outdoor clinic that served rural Pathan women. Let's say the initial setup was less than satisfactory: Mum spoke only Bangla and English, the patients spoke only Pashto, and an assistant who doubled as an interpreter spoke only Pashto and Urdu.

But my mum is not a quitter. In six months she spoke fluent Pashto and Urdu. My parents scrimped and saved and left for England for postgraduate training.

It was an intrepid, risky endeavour. England at that time was flush with medical doctors from Commonwealth countries and my parents exhausted all their savings and still failed to get a job. To complicate matters, they had me in tow, then a toddler. The remarkable tale of how my dad landed a job is a story for another day, but that brought a welcome change in their fortunes.

Soon my mother got a job as an anaesthetist. Britain's National Health Service was then at its prime. Mum was trained, with great care, by expert consultants. The reasons were not altogether altruistic—as soon as they were sure of my mother's skills, they had more free time.

My parents returned in the late 1960s in erstwhile East Pakistan, and mum discovered that anaesthesiology here was at least 50 years behind. Fresh with her training from British teaching hospitals, she went about bringing anaesthesia departments up to speed. Through her own work as well as through personally training countless anaesthetists, she helped bring about a sea change in the practice of anaesthesiology in Bangladesh.

As I look back at the past 50 years, I marvel at how she handled her responsibilities. In addition to her responsibility as a professor, she had a private practice serving a number of clinics. And on top of it all she ran our household. The workload was back-breaking. A typical day could begin with scheduled operations at private clinics as early as 6:00 am (everybody had to be at work by 9 am). Then mum would go to the hospital where she was a professor. She would finish at around 2 pm. There could be scheduled private operations during the afternoon. Then there could be emergency caesarean operations to attend, which could be at any hour—I remember mum going out at 3 am or 4 am.

She did it all with effortless grace and joy of spirit.

I think those of us who grew up during that time fail to recognise what stellar role women like my mum played in establishing a solid foothold in the workplace for women. Mum's welcome break during work was hanging out with some of the top female gynaecologists of that time, many of whom are no longer with us today—Professor Sofia Khatun, Professor Suraiya Jabeen, Professor Niloufer Aftabi, Professor Shahla Khatun. All these women, like the other handful of women in high positions in academia and elsewhere at that time, made it abundantly clear to the worst sexist of the day how wondrously capable they were.

I've never gotten around to telling mum how much I've always admired and loved her. I don't expect I ever will. One of the poignant facts of life is that some of our deepest feelings for people we care about the most are destined to remain unspoken. However, I do draw some solace from the fact that beneath that façade of placid sweetness, my mum is an acutely perceptive judge of people—and she knows in her heart what I cannot bring myself to say.

Heartiest congratulations, Amma.

Ashfaque Swapan is a contributing editor for Siliconeer, a monthly periodical for South Asians in the United States.

Comments