Why 1971 still casts a shadow in Bangladesh-Pakistan relations

The people of Bengal played a pivotal role in the formation and blossoming of the Muslim League and, ultimately, the creation of Pakistan. However, the gratitude they deserved was never returned. Instead, once Pakistan came into being, the West Pakistani leadership systematically turned its back on the very people who had helped establish the country.

The people of East Pakistan faced a wave of discriminatory measures in every sphere of public policy. Bengali culture, rights, and voices were systemically suppressed and subdued.

Despite contributing the lion's share of Pakistan's exports, East Pakistan received a meagre proportion of the country's investment and foreign aid. Power, resources, and decisions remained concentrated in the hands of West Pakistanis.

When a political party from East Pakistan secured a comprehensive majority in the 1970 elections, the West Pakistanis refused to honour the people's will. Their answer to the ballots came in the form of bullets. What followed was not just repression—it was a deliberate and brutal attempt to erase a people's demand for dignity and autonomy.

On the night of March 25, 1971, the marauding Pakistan Army descended upon unarmed civilians of East Pakistan, imposing war on them. Over the next nine months, Bengalis endured unspeakable horrors. Hundreds of thousands were killed in a campaign of genocide, and countless women were subjected to sexual violence. These atrocities were not mere accidents of war or collateral. They were calculated acts aimed at annihilating the Bengalis.

The truth of the 1971 Liberation War remains buried under denial, distortion, and more recently evasion. More than fifty years on, Pakistan has neither acknowledged this genocide nor apologised for it. School textbooks in Pakistan feed generations with distorted narratives, blaming "Hindu teachers" and "international conspiracies" for the fall of East Pakistan.

Toronto-based Pakistani oral historian Anam Zakaria, in her 2019 book "1971: A People's History from Bangladesh, Pakistan and India", states that Pakistan's narrative about Bangladesh has been far too simplistic and "myopic." Zakaria quotes Pakistan Studies textbooks for ninth and tenth grades, endorsed by the country's textbook board: "The Indian leadership in general did not agree with the idea of creating a separate homeland for the Muslims. When Pakistan was created to their entire displeasure, they started working on the agenda of dismembering it without delay."

East Pakistan had a significant Hindu population which, unlike West Pakistan's Hindus, had deep pro-India sympathies. In many schools, colleges, and universities, Hindu teachers outnumbered Muslim teachers. Over time, these institutions virtually turned into nurseries for breeding anti-Pakistan and secessionist intelligentsia. These intellectuals played a decisive role in dismembering Pakistan. East Pakistani masses, deprived and oppressed by West Pakistan, became easy prey for the secessionists, the textbook claims.

This exemplifies how Pakistan refuses to accept the calls of Bangladesh and denied the oppression Bengalis suffered in the hands of Pakistan.

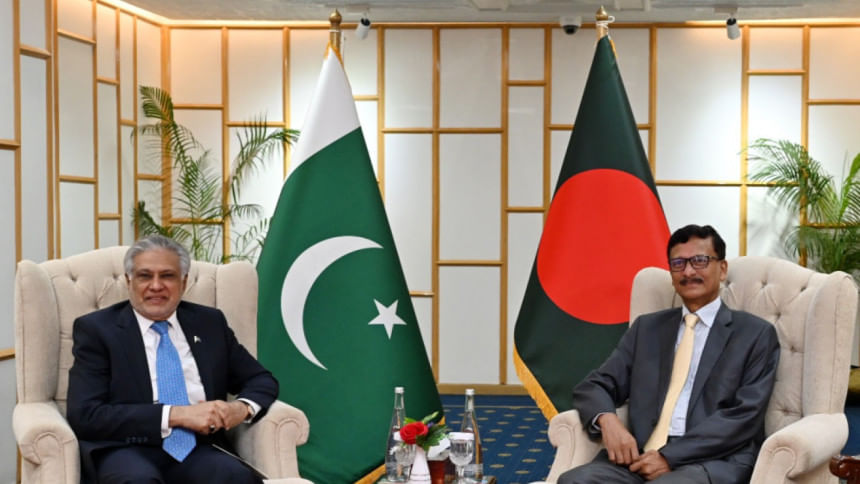

Pakistan's foreign minister, Ishaq Dar (also the deputy prime minister), said on August 24, the 1971 issue has been addressed before when in fact it really has not. The 1974 treaty does not address the issue, neither did Pervez Musharraf. Touhid Hossain has said as much as well.

Dar's comment is quite in line with Pakistan's evasion of a grave issue, which in turn remains a source of pain and disappointment among Bangladeshis. Commentators and political actors appear to agree that meaningful progress in Bangladesh-Pakistan relations requires that Pakistan acknowledge its role in genocide and bring about a conclusive closure. This does not mean the relations of the two countries should remain at a standstill as Touhid Hossain also indicated, and quite rightly so.

Political and diplomatic ties had become increasingly cold to become almost non-existent over the last 15 years of Hasina rule.

Dhaka has repeatedly urged Islamabad to acknowledge the genocide and apologise for it, but every appeal has only been met with silence. During the April 17 meeting between foreign secretaries after 15 years, Bangladesh raised these long-standing issues once again—apology for genocide, return of stranded Pakistanis, and share of pre-1971 assets.

However, neither side should let the past hold them back from establishing friendly relations and foster commerce and trade to the benefit of both the nations. At the same time India should not consider this improvement of relations as Bangladesh getting into the Pakistan's political fold. There is much potential in a south Asian alliance in the form of SAARC that remains in limbo owing to the open antagonism between the nuclear powers of the subcontinent, which only deprives the people of potential growth and prosperity though increased economic cooperation and friendly ties.

However, it should still be pointed out that the one must reconcile with the past for misdeeds and not brush them aside with vague references if only to bring about closure on both sides. There are a number of such examples elsewhere in the world.

In 2022, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte apologized for the Netherlands' colonial violence in Indonesia. Japan, in 2016, apologized to South Korea and pledged approximately $8.3 million as compensation for its use of Korean "comfort women" who were forced to work in Japanese brothels during World War II. President Jacques Chirac, in 1995, acknowledged that the French state was an accomplice in the deportation of tens of thousands of Jews during World War II. The U.S. Congress passed a law in 1988 apologizing for the internment of Japanese Americans during WWII. Germany's Chancellor Willy Brandt fell to his knees at a memorial for Holocaust victims in 1970 in a powerful symbol of remorse.

To conclude, we ask again, if they can do it, why not Pakistan?

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments