Trump’s tariff tsunami drowns global order

For Indian exporters, the news from Washington last week felt less like a trade policy announcement and more like a declaration of economic warfare. A staggering 50 percent tariff has been imposed on Indian goods, a move justified by the White House as a response to India's ongoing trade with Russia. The irony, however, is as steep as the tariff itself: the United States, the very nation wielding this economic hammer, continues its own commerce with Moscow, particularly in strategic materials.

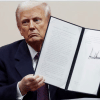

This action against India is not an isolated incident but the latest and most jarring act in a global drama where the rules of trade have been systematically dismantled. What began as an election pledge to correct trade imbalances has spiralled into a chaotic, unilateral strategy, culminating in a move that has sent shockwaves from New Delhi across the world. The shock in diplomatic circles is tempered only by a grim sense of familiarity; this is the playbook of US President Donald Trump, where trade law has become a weapon for political whim.

The pattern is undeniable. The world has watched as tariff threats were reportedly levelled against Canada not for unfair trade, but for its diplomatic decision to recognise Palestinian statehood—an action that drew private condemnation from other G7 allies concerned about the precedent. Brazil was similarly threatened, not over commerce, but allegedly for pursuing the domestic prosecution of Brazil's former President Jair Bolsonaro, a political ally of the White House—a move that legal scholars decried as a flagrant attempt to interfere with the sovereign judicial process of another nation. These are not trade disputes; they are raw geopolitical power plays, using the language of economics as a thin veil to cloak a bare-knuckled approach to international relations.

At the heart of this strategy is the manipulation of US law. The administration's legal arsenal consists of decades-old statutes, now being stretched to breaking point. Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, born out of Cold War fears of being unable to produce tanks and ships, was designed to safeguard national security by protecting critical defence industries. Today, its definition has been contorted to label economic competition from staunch allies in the automotive and steel industries as a "threat."

Similarly, Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 was created during an era when the US was grappling with the rise of Japan and sought tools to combat specific unfair practices, such as intellectual property theft or closed markets. It has since been transformed from a scalpel for targeted disputes into a sledgehammer, used to launch a full-scale trade war with China that has cost consumers and producers billions. Finally, the powerful International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) of 1977, a tool designed to sanction states like Iran or North Korea, has been invoked to declare a "national emergency" over immigration, turning a humanitarian and logistical issue into a pretext for economic sanctions. The chasm between the original intent of these laws and their current application is vast.

It was not always about such geopolitical chess moves. The original argument, sold to millions of US voters during fiery campaign rallies, was simpler: fix the trade deficit. The theory was that tariffs would act as a protective wall, making foreign goods more expensive and forcing a renaissance of US manufacturing. The renegotiation of NAFTA into the USMCA stands as the primary exhibit for supporters, who argue that the threat of tariffs forced Mexico and Canada into a deal more favourable for US workers. However, many economists argue that the changes were largely cosmetic and that the agreement's real-world impact has been minimal, making the "victory" more of a public relations achievement than a substantive economic shift.

The consequences of the broader strategy are now a daily reality, rippling across the globe. Businesses, from small suppliers to multinational corporations, face crippling uncertainty, postponing capital investments and hiring plans. A tit-for-tat cycle of retaliation has hurt US farmers, who lost access to the Chinese market, as much as their foreign counterparts. Most critically, the trust that underpins the global, rules-based trading system—centred around institutions such as the World Trade Organization (WTO)—is evaporating. The WTO's appellate body, which acts as a supreme court for trade disputes, has been rendered irrelevant, leaving nations with little recourse beyond direct retaliation.

One long-term consequence, however, could be the accelerated push towards de-dollarisation. With the US increasingly willing to use its economic and financial might as a tool of coercion, nations are growing wary of their dependence on the US dollar. This "weaponisation of the dollar" makes holding dollar reserves or relying on the US-centric financial system significantly risky for any country that might find itself at odds with US foreign policy. To insulate themselves from this vulnerability, countries from China and Russia to Brazil and other BRICS nations are actively building parallel systems for trade settlement, such as yuan-ruble or rupee-ruble mechanisms. This erosion of the dollar's status as the world's primary reserve currency could have significant long-term implications for US's ability to finance its national debt and exert global influence. Moreover, the US domestic economy might also suffer, as the cost of living, especially for low- and middle-income households, may rise.

President Trump's ultimate goal appears to be a world remade to his transactional specifications—using economic force to bend nations to his will, disrupting existing alliances to forge new, more favourable deals. But can this truly be achieved? The global economy is not a series of bilateral deals to be won or lost; it is a complex, interconnected ecosystem. Disrupting it unilaterally has, so far, sown more chaos than it has reaped clear victories, creating inflationary pressures at home and resentment abroad.

The lessons from this era are being written in real time, in the frantic calculations of businesses and the strained conversations in foreign ministries. We are learning that using economic tools for political ends is a high-risk gamble that can inflict long-term reputational damage, portraying the US not as a reliable partner but as an unpredictable actor. We see that unilateralism has limits and can spur the creation of new trading blocs that actively seek to bypass the US economy and its currency. Most importantly, we are witnessing a direct challenge to the post-World War II liberal order, which, for all its flaws, provided a framework for unprecedented global prosperity.

As India grapples with this latest tariff onslaught, the world watches and asks: is this aggressive posturing a means to a new, more favourable US-led order, or is the chaos itself the end goal? The answer will define the landscape of global commerce for a generation to come, determining whether we move towards a future of managed cooperation or one of fractured, zero-sum competition.

Hussain A Samad is a development researcher at the World Bank in Washington, DC. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments