Student union elections: Rescuing the universities from decline

After many years, student union elections are going to be held in Dhaka, Jahangirnagar, and Rajshahi universities. This is a good development, and I hope the elections will be fair and free from violence or intimidation, and the students will be able to participate in them safely. If student unions in all universities are formed through credible elections regularly, genuine young leadership will be able to emerge in the country.

However, public universities are currently facing numerous problems, and their credibility has been severely diminished. Those who still opt to study in public universities often worry about session jams, campus violence, quality of education, or whether classes and exams would take place properly. The trust that these universities once commanded has eroded, creating a wide gap between public expectations and present realities. We must identify the causes of this decline and address them.

During the British colonial period, Dhaka University was established in 1921 as the first public university in present-day Bangladesh. In the Pakistan era, other big public universities were established: Chittagong University, Rajshahi University, the agricultural university (now BAU), the engineering university (now BUET), and Jahangirnagar University. After independence, particularly in the past two decades, many more public universities were established. In the early 1990s, private universities first came into being. At the same time, several colleges were upgraded into universities—Jagannath College to Jagannath University, for instance. As a result, the numbers of both public and private universities has increased significantly, though this rapid expansion has created serious concerns about their quality, role, and governance.

The core issue here is how public universities should function: what the role of teachers should be, how student activism should run, how students' rights and safety are preserved, how education and research should get proper priority. The history of public universities shows that much of this depends on the government: how it perceives universities, what role it plays, and what it wants from universities.

Student union elections in Bangladesh began in the early 1970s, though the first one was marred by violence. They resumed in the late 1970s, and during the 1980s, under Ershad's autocratic rule, several elections were held as students were united against military dictatorship. But after elected governments returned in 1991, both the BNP and the Awami League, when they came to power (along with Jatiya Party and Jamaat-e-Islami), sought to seize full control of the universities. They relied on two main instruments for that: installing a spineless administration by appointing compliant and subservient teachers to various posts, and by patronising their student wings to dominate residential halls and campuses through violence.

Whichever party came to power, its student organisation gained overwhelming dominance while all other groups were silenced or marginalised. Among many teachers, a culture of obedience and opportunism developed in the process.

This reached its most extreme form under the Sheikh Hasina government. Vice-chancellors were appointed based on loyalty rather than merit, and many actively facilitated corruption, tender manipulation, extortion, and violence by ruling party student organisations. Universities, especially residential halls, became places of fear, while research and academic work were neglected. Many teachers competed for favour with the authorities instead of focusing on scholarship.

Another serious problem has been the increasing commercialisation in public universities. Many public universities introduced weekend and evening programmes that operate like private ventures, charging high fees. Teachers also began working at private universities. While supporting the privatisation drive, the World Bank argued that private universities would create healthy competition and raise standards of both. In practice, both public and private universities have been suffering due to substandard quality. Public university teachers have been diverting their time and energy to commercial programmes and working part-time at private universities, while many private universities—operating on a profit-driven model—have been relying mostly on part-time teachers to minimise costs. Students in both systems have been left without proper academic attention.

In fact, a combination of neo-liberal policy and violent authoritarianism has caused a disastrous effect on university operations. As a result, the country's higher education system has become increasingly driven by money rather than scholarship. It is true that a number of teachers enjoy financial comfort from these extra income opportunities, but the quality of teaching and research has deteriorated. Students in residential halls live under the domination of partisan leaders engaging in extortion and intimidation. Teachers, meanwhile, are distracted from research and academic development, focusing instead on personal gain or appeasing the authorities. The government appears content with this arrangement, investing heavily in construction projects that often serve as vehicles for corruption rather than academic progress.

What is needed instead is a return to the original mission of public universities: to serve as the centres of learning, research, and free thought, dedicated to public interest rather than the ruling parties or private profit.

To overcome the present crisis, student politics must be revitalised in a creative and visionary manner. Student leaders need to play a constructive and responsible role to ensure desired changes in universities, especially public ones. Elections should not be about winning power alone but about rescuing public universities from decline. Students and teachers must agree on certain principles: universities should be autonomous, free from government interference, and supported only in their academic and research functions. Appointments must be based on merit, not political loyalty. Students must not be used to engage in extortion, tender manipulation, or violence. All forms of discrimination—class, gender, religious, and ethnicity—must be opposed. Public universities must remain public in character.

If the upcoming student union elections can inspire this shift, they may mark the beginning of a much-needed change. Genuine reform requires not only the courage of students and teachers, but also the awareness and support of the wider society. Moreover, the approach of the government towards universities must go through a fundamental change. They should leave universities to education and research, and not use them as an instrument for extending ruling party dominance through unwanted intervention, violence, and corruption.

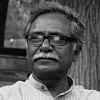

Anu Muhammad is a former professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments