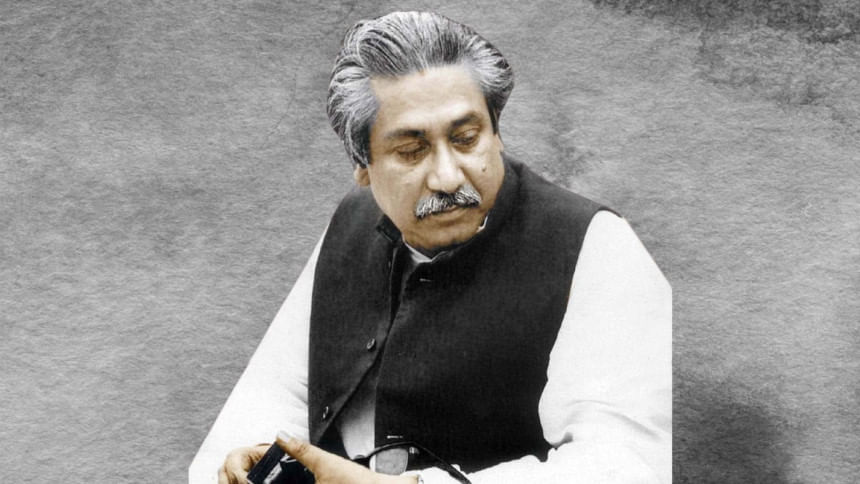

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Bangladesh’s unfinished reading

Half a century after his assassination, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is less a historical figure than a layered palimpsest—written, erased, and reinscribed in contested strokes. Silences around his legacy speak as loudly as tributes: between sanctification and omission lies a spectrum of memory, where presence is haunted by absence, and the nation's founding myth is both celebrated and disputed. He also bore the shadowed face of a leader whose centralising instincts undercut the democracy he had fought to achieve.

Sheikh Mujib's life evokes enduring literary archetypes. Like Janus, he looked both to dawn and dusk: the liberator before 1971 and the centraliser thereafter. Like a Shakespearean tragic hero, his greatest strengths—moral conviction, unyielding resolve, political vision—carried seeds of overreach. And, in the manner of Conradian protagonists, he was riven by contradictions: ideals clashing with exigencies, ambition colliding with reality, each decision haunted by the tension between intention and outcome.

Distinctively, the beleaguered leader spent nearly nine years imprisoned under successive Pakistani regimes, much of it in solitary confinement. This crucible empowered him to develop the resilience to distil the grievances of a silenced majority into the Six Points, a manifesto that transformed anger into disciplined articulation and made Bangalee autonomy feel inevitable. In pre-1971 Pakistan, his speeches became incantations, summoning a people into being. The potency of his speeches lay not only in vision but in conferring legitimacy on a majority long denied recognition.

Before liberation, Mujib's role had the clarity of a Shakespearean hero in the first act. He was charismatic and indispensable: a figure whose authority carried metaphysical weight, fusing popular anger with strategic precision. Yet, the very traits that made him essential—moral certainty, resolute will, and unflinching adherence to principles—would later cast long shadows. His pre-liberation persona foreshadowed post-independence challenges, where statecraft often collided with ideological purity.

Liberation is never a clean slate; it is a palimpsest upon which the next inscription begins. Mujib returned to a devastated Bangladesh like a Conradian figure stepping out of the wilderness: triumphant yet burdened by war, famine, and fractured governance. Ideals that had carried him to victory collided with the exigencies of state-building. Faced with economic collapse, political fragmentation, and social unrest, he opted for centralised control. The formation of BAKSAL in 1975, a one-party system dissolving political pluralism, was an act of overwriting, imposing unity over dissent and order over chaos. In Derrida's terms, the erasure was incomplete: silenced dissent lingered as a ghost text, destabilising the authority he sought to consolidate.

Like King Lear, Sheikh Mujib conflated indispensability with the survival of the state. Hubris that had been a weapon in resistance became a liability in governance, undercutting the vindication of a leader "more sinned against than sinning." Every banned newspaper and every imprisoned dissenter became an invisible countertext eroding his authority. His flaw was presumably structural, latent even in pre-liberation, awaiting the conditions of power to reveal itself.

The events of August 15, 1975—his assassination alongside most of his family—tore the political script from his hands. Yet, this erasure was overwritten: Mujib the martyr, Mujib the eternal father. Death purified the image, soft-focusing the authoritarian turn behind grief. The bad faith is double-edged: sanctifying the man to honour achievements while obscuring contradictions, and weaponising that image for successors who inherited both legacy and flaws.

Sheikh Hasina's political life began in the long shadow of her father's absence—personal grief fused with statecraft in a mission that started for justice and hardened into political authority. In 15-plus years of autocratic rule, she arguably reshaped both her father's legacy and the Awami League into instruments of dynastic continuity, subordinating the revolutionary promise of 1971 to political imperatives, while dissenting counternarratives remained systematically buried. The revolutionary vision of liberation became increasingly framed through the lens of contemporary political objectives rather than the ideals that had catalysed it.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's trajectory mirrors Conrad's darkest truth: the line between liberator and autocrat is drawn in shifting shadows. Like the Company's agents who sailed upriver bearing civilisation only to embody the savagery they despised, he carried democracy's torch into Bangladesh's founding darkness only to find its flame casting authoritarian shapes on the newborn state. His arc also mirrors Lear's division of kingdoms: the patriarch who mistook symbolic centrality for permanent authority. Following independence, he became a prisoner of his own unbound ambition, tethered to the authority he had wielded in forging it. His fatal miscalculation echoed Lear's: believing the nation's love required perpetual stewardship. When storms came—like the famine of 1974 and coups—he raged against betrayal of his vision, blind to how absolutism that forged the state now fractured it.

In postmodern terms, Sheikh Mujib's legacy exists as a Derridean palimpsest: every state-sanctioned tribute overwrites but cannot erase suppressed counternarratives. Archival traces persist—his 1971 speeches promising democracy bleeding through the ink of BAKSAL's one-party decrees, like Lear's love test collapsing under performative contradiction. The bad faith lies not in honouring the liberator nor critiquing the autocrat, but in pretending that these were separate men. For Bangladesh, this is the foundational aporia: the father who authored the nation and inscribed its first authoritarian chapter, oscillating between presence and absence like the ghost of Hamlet's murdered king.

Fifty years on, Bangladesh continues to read and reread this layered text. Political forces following the July uprising last year actively reshaped the founding narrative, subordinating liberation and early leadership to contemporary imperatives. The truth lies in the tension between layers: the liberator and the autocrat were two faces of the same Janus, bound to one head. This contradiction cannot be resolved by selective remembering or erasure.

The palimpsest metaphor extends beyond Sheikh Mujibur Rahman himself. Each generation of leaders, historians, and citizens adds inscriptions, interpretations, and omissions to the evolving narrative of Bangladesh's origin. Commemorative statues, textbooks, and official ceremonies act as inscriptions, while omissions, silences, and erased dissent form the ghostly countertext. Understanding the nation requires reading both layers, letting presence and absence speak at once.

Here, the mirror and lamp imagery illuminates the task of historical reflection. Sheikh Mujib's life acts as a mirror: it reflects Bangladesh's struggles, hopes, and contradictions back to the present. Citizens and leaders peer into this mirror, confronting both inspiration and caution, seeing themselves in the glare of triumph and failure alike. The lamp represents the light of legacy, illuminating paths forward even as shadows of erasure persist. Together, mirror and lamp compel us to reckon with a legacy neither monochrome nor immutable, but richly textured, paradoxical, and deeply human.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman's legacy is unfinished, a living document in which Bangladesh continues to negotiate power, memory, and identity. The interplay of celebration, critique, and selective amnesia reveals the stakes of historical interpretation: the past is never inert, and every act of remembrance carries a contemporary purpose. As political forces, journalists, scholars, and citizens navigate this contested terrain, the challenge remains to honour the complexity of the man while grappling with ongoing reverberations of his actions.

Dr Faridul Alam is a retired academic and writes from New York City, US.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments