'Guha was as much an intellectual and thinker as he was a historian'

Ranajit Guha ( May 23, 1923 - April 28, 2023) was an influential Indian historian and scholar renowned for his groundbreaking contributions to the field of Subaltern Studies. His approach to historiography has had a profound impact on the field of history, both in India and globally. His ideas continue to influence scholars, prompting critical examinations of power, agency, and resistance within historical narratives. Guha's legacy lies in his efforts to bring the stories of the subaltern to the forefront, challenging dominant historical interpretations and fostering a more comprehensive understanding of the past. In this interview with Priyam Pritim Paul, Dipesh Chakrabarty, one of the founding members of Subaltern Studies and the Lawrence A. Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor of History at the University of Chicago, provides insights into the life and significant contributions of Ranajit Guha.

You wrote that Ranajit Guha was your guru and friend. How does the relationship of guru and friendship mutually build or contribute to making thinkers like you and so many other historians?

Ranajitda had both the manner and the intellectual make-up of a guru-like teacher. He was clearly ahead of us in reflecting on several problems that dogged the received historiography of South Asia.He could demonstrate, through his own research and writing, ways of addressing these issues and had a vision of subaltern history that inspired us all. He also knew how to be a co-learner with us who were like his students. So being a "guru" did not necessarily mean any kind of oppressive hierarchy in our relationships. There was much friendship as well. Besides, he hand-picked the people he wanted to work with. None of us were formally his students. The only ingredient that bound us together was the excitement over the ideas that he had to share and his capacity to generate an intellectual conversation that created a sense of community among us. And because it was a group that was put together by him, it made you feel "chosen." He was special in that way. He did not much care for institutional conventions – this was not always well received by others – but this way he could build a sense of a group with a historiographic mission that had serious implications about how to understand modernity and the modern-political in the context of South Asia.

Amartya Sen said Guha was the most imaginative Indian historian of the twentieth century. Would you agree with him? Why?

He was original, imaginative, and brilliant, without a doubt. I would refrain from deciding if he was "the best" among his peers as that would once again take us back to another theme Sen has also elaborated on – the obsession with first-boys in the subcontinent. Originality was the hallmark of all of Guha's writings. A Rule of Property for Bengal insisted on and demonstrated the importance of ideas in colonial economic policy-making in India long before any other historian – with the sole and remarkable exception of Eric Stokes - turned to the subject. And you only have to read Stokes and Guha together to see the difference in Guha's approach. He was also the first historian in Indian history to seriously introduce "structuralist" ways of thinking. This gave us some very interesting means for thinking about that which, in India, seemed "archaic" in the very middle of the "modern." This he achieved during his Subaltern Studies days. His essays like "The Prose of Counter-Insurgency," "Chandra's Death" are brilliant expositions of his thoughts on reading the archives and the necessarily episodic nature of "subaltern" histories. You may or may not agree with his conclusions, but you would not be left in doubt of his creativity and brilliance. He was also a very gifted and self-conscious writer of prose in both English and Bengali.

How did he organise a group of young historians like you in forming the seminal Subaltern Studies group and what was his method of providing intellectual insight to those who were not his direct students?

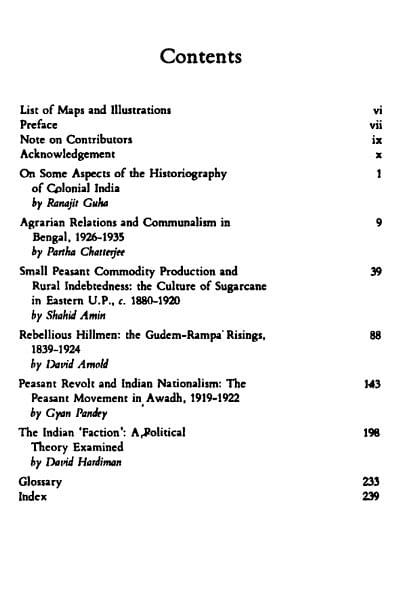

As I said, he hand-picked people or they chose him. He started with two doctoral students at Sussex – David Arnold and David Hardiman – and two doctoral students at Oxford. The two Davids worked with Anthony Low who was later my supervisor as well in Canberra. The students from Oxford, Gyan Pandey and Shahid Amin, worked with Tapan Ray Chaudhuri for their doctoral degree. When I look back on this, I realise that this could not have been an easy situation for either Anthony and Tapanda but they were both temperamentally generous and intellectually secure enough to let their students draw inspiration from what Ranajitda had to offer. These four people formed the oldest nucleus of what became Subaltern Studies. By the time Partha Chatterjee, Gautam Bhadra, and I came into the group, its basic tenets had been worked out and given a form in writing. But we all found them exciting. The agenda for history-writing that the group had worked out and that Ranajitda had set down on paper acted as some kind of a manifesto for the group. It was also new and inspiring.

Why can his book Elementary Aspects of Peasant Insurgency be considered a groundbreaking work that laid the foundation for Subaltern Studies worldwide?

Well, even if it did not lay down a universal foundation for subaltern studies worldwide – that would not have been Guha's claim either, for he always spoke of "convergences" of agendas and aspirations of different historiographies. Guha breathed new life into the word "subaltern" and the concept of subaltern histories that were relatively independent of elite actions. But Elementary Aspects was undoubtedly a novel work. It was truly heroic of Guha to examine closely the histories of more than a hundred peasant rebellions in nineteenth-century India and then build up a model for understanding patterns in collective rebellious behaviour of peasants, and to develop some deep insights into the insurgent consciousness that, Guha argued, underlay such behaviour.

How do you perceive the philosophical trajectory in Guha's thought, which encompassed Tagore to Hegel or the Indian tradition with modern European thought?

Guha thought of the discipline of history in the subcontinent as something that could not be separated, in its intellectual origins, from the history of the colonial state. For, colonial officials of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries wrote modern "histories" as part of administrative documents. Disciplinary history, for Guha, was thus what some might today call "colonial knowledge." It was part of the discourse of the colonial state and could never be separated from statist concerns. He found Hegel to be the philosopher of such a statist idea of history, and he wanted to oppose to that tradition Tagore's thoughts on human pasts, thoughts that always saw the modern state as something profoundly alien to the spirit of "Indian" society.

Why has colonialism been his primary area of interest for a long time? Why did he shift his focus from Gandhi to peasants in order to gain a deeper understanding of them?

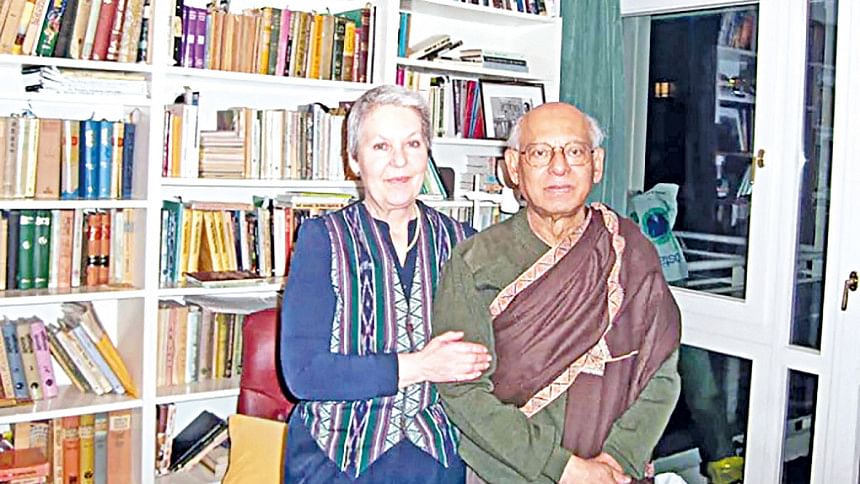

This has something to do with certain facts of his life: he grew up in the last twenty-five years of colonial rule, came under the influence of the Communist Party, understood the predicament of his own class, Bengali landlords and the bhadrolok generally, as being a result of colonial rules and policies. Gandhi interested him deeply – how could he not, it was Gandhi who connected the nationalisms of the urban and upper classes in India with the worlds of the peasantry. In fact, the last class Guha ever taught, as a visiting professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz, was on Gandhi. He also would have retained a long-term interest in peasant movements, given the history of Bengal in the 1940s. But the interest in writing about peasant insurgency probably arose out of his interactions with young Naxalites of Delhi in 1970 when he and his wife spent a year in the country on sabbatical leave.

Which were his other areas of interest besides history?

Philosophies of history and language. Also, philosophies of Sanskrit grammar, theories of enjoyment in Sanskrit (rasatattva), Tagore, Bengali poetry and literature in general.

How do you assess his later works, written in Bengali from Vienna, concerning literature and philosophy?

I cannot provide a thorough evaluation since I have yet to read them carefully. However, based on what I have seen, his works are filled with stimulating thoughts and questions.

What was Guha's opinion on the idea and formation of Hindutva in India?

Like many others, he would have been opposed to it, and opposed to their attempts at distorting history.

What was Guha's perspective on the partition of Bengal in 1947?

Never discussed this specifically. He was unsentimental about it and seemed to have accepted it as a fact of life. But when I visited him in March this year, I asked him if he thought of his early days in Barisal in these final years of his life. He said, "a lot. I think of my childhood days in Barisal all the time."

Do you believe that the extensive discussions about Guha's legacies following his passing will reignite a debate on historiography or the approach to writing history in South Asia?

I hope it does. That would be the best outcome. Among all the tributes, however, there has already been a piece that I thought was particularly ungenerous, intellectually speaking. But that's how often South Asian academics argue, by putting people down, by dismissing their contributions, by ridiculing them. Maybe all this will eventually give rise to a debate that can elevate itself above the rhetoric of insults.

Having known Ranajit Guha for nearly five decades and being one of his close associates, considering Guha's life, what advice would you give to young historians?

That is a tough one. Best not to give any advice. An intellectual biography of Guha, if ever written, will make for a fascinating story of one very gifted Bengali-Indian intellectual and historian, living in self-exile for the majority part of his life but forever focused on the country he chose to leave, trying to make historical sense of life and politics as he had seen them. Perhaps others will draw their own lessons – not just academic lessons but lessons for life - from the substantial number of writings he has left behind. For at the end of the day, Guha was as much an intellectual and thinker as he was a historian. I think it would be wrong to reduce him simply to that last category. He looked upon History, the discipline, as a gateway to more general forms of thinking.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments