Can't afford another lost decade for education

Whenever the issue of education surfaces in Bangladesh, policymakers across the political spectrum tend to strike a familiar chord. "Education is our top priority," they harp.

This phrase has become so common that it has virtually turned into a cliché as it is repeated endlessly, yet rarely reflected in our national priorities.

Over the past decades, Bangladesh has endured devastating natural disasters, a crippling pandemic, and turbulent political transitions.

Amid all of this, one sector that has persistently borne the brunt of instability is education. Schools and universities remained closed for months on end during the COVID-19 crisis.

Students—particularly those from underprivileged and rural backgrounds—suffered enormous learning losses.

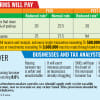

Though education was the first victim of crises and it was hardly prioritised with attention or allocation. Since 2009–10 fiscal year, which marked the beginning of the Awami League's extended stay in power, the allocation for education was less than 2 percent of GDP. There were exceptions in 2009-10 and 2016-17, when allocation was 2.04 and 2.49 percent of GDP respectively.

Since 2016–17 fiscal, allocation in education never touched the 2 percent mark.

Again, the budget for the education sector has remained around 11 to 12 percent of the national budget for nearly 16 years. This falls well short of UNESCO's recommended 4–6 percent of GDP or 15–20 percent of the budget.

One cannot ignore the political economy behind this trend. Over the years, infrastructure and mega projects—such as highways, flyovers, power plants, and bridges—have commanded the lion's share of public investment.

These projects, many of them essential, but many others have often been seen as lucrative opportunities for politically connected business interests and syndicates to make a quick buck.

In contrast, investment in education lacks immediate visibility or commercial returns, and thus has never truly captured the political imagination.

The student-led mass uprising on August 5 brought a new wave of hope. The interim government that emerged from this unprecedented civic movement led by students had a unique opportunity to do things differently, to recast the national budget with a vision for long-term human development and reorder national priorities—placing education at the centre.

But the proposed allocation for 2025–26 has been disheartening. Tk 95,644 crore for the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Primary and Mass Education, though appearing sizeable, translates to just 1.72 percent of GDP and 12.1 percent of the budget.

This is not the budget we were waiting for. We need proper budgetary allocation along with a vision that sees students not as political tools or numbers in exam statistics but as future scientists, thinkers, artists, and leaders.

Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in access to education, but quality and equity remain major concerns.

We need sufficient number of qualified teachers, effective training, better classroom facilities, higher research funding, increased use of technology in education, and curriculum reform that reflects both global knowledge and local needs.

There should be increased attention to addressing disparities in terms of infrastructure, teachers, and access to quality education in rural areas and among marginalised communities. This is easier said than done. For instance, teachers' salary has been typically so low that bright students hardly show interest to become teachers. We need better pay and perk to acquire and retain qualified teachers.

And all this requires money.

If we want a resilient, forward-looking Bangladesh that competes in the global knowledge economy, we must recognise that educational institutions are not expenses—they are investments. The return on this investment is priceless.

To maximise the effective utilisation of the education budget, the government should implement a robust oversight mechanism that ensures transparency, accountability, and proper allocation of funds. It is important to establish an independent audit committee and a digital system to ensure transparency in the use of education and research funds.

The youth of Bangladesh have shown they are willing to rise, mobilise, and demand change. It is now up to the government—interim or otherwise—to listen, act, and invest accordingly.We cannot afford another lost decade for education.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments