I remember Kamla Bhasin through her children’s books

Words fall short to describe Kamla Bhasin: how does one begin to describe a force of nature like her? Perhaps the simplest way to do so is with the word 'love'. Kamla was many things to many people—most famous for her fierce feminism, activism, and work in development, rights, peace and justice. However, at the core of it, I believe, Kamla embodied love.

It was her love of people—and of doing right by the people she loved so dearly—that made her work feel so accessible to everyone. 'Accessible' feels like a good word to describe Kamla as well. Despite being so beloved across borders, particularly in South Asia, Kamla never came across as aloof or distant. She was always there, on the ground, right beside you. It is what makes her work so special.

Kamla founded Sangat, a South Asian feminist network, and co-founded Jagori, a women's resource centre after leaving her job of 25 years with the UN's Food and Agriculture Organization. She was also the South Asian coordinator of the One Billion Rising campaign. Through these organizations, and through collaborations with individuals and institutions across South Asia, Kamla strived for gender justice and equality. She was one of the leading forces of the South Asian feminist movement, having shaped the outcomes of protests against dowry and having impacted the anti-rape laws in the country as well as the rhetoric around sexual assault and violence, the famous Shah Bano divorce case, and more. To attempt to capture Kamla's legacy in this article would be doing it a disservice, for the extent of her impact on women's rights and the richness of her knowledge and compassion can fill pages upon pages of text.

She had immense talent in breaking down complex concepts to their simplest essence so everyone can grasp them. The books she wrote on gender, patriarchy, masculinity and more, which have been translated and adopted into several Women's Studies courses, never feel too difficult to understand. I remember her telling us once, as we sat around the table having tea, that it does not make sense to write in academic jargon that very few can make sense of. It was an off-hand remark, as we shifted from story to story as Kamla regaled and entertained us. However, it was one that stuck with me through anything I tried to write.

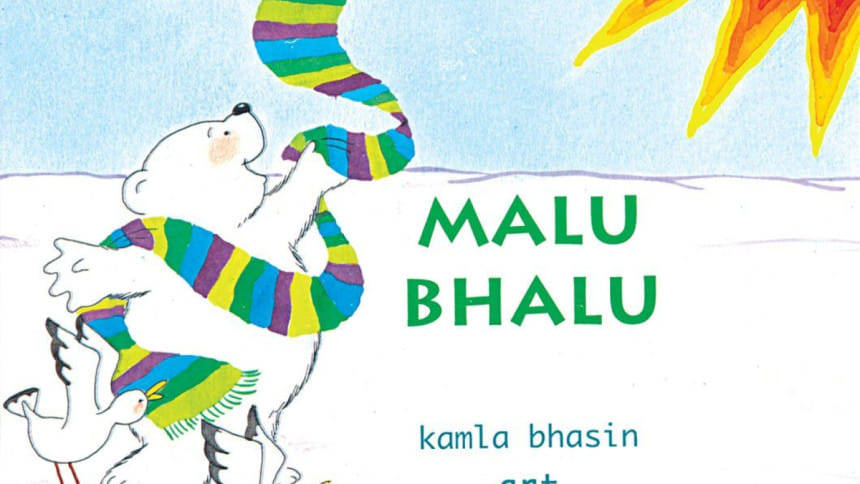

In that vein, I must admit that my favourite works by Kamla are not her books on feminism. Important as they are, I believe her true talent lay in the witty rhymes she crafted for children's books. In a world where many are still struggling to find compassionate, feminist books to read to children, Kamla left us a treasure trove. Her children's books unpack the need to humanise mothers, they explore gender roles, and her more recent books, such as the one about her iconic, little red electric car, Laal Pari, also discuss environmentalism. There is something magical in being able to distill these important, relevant messages into easy-to-grasp rhymes that we can teach to our children.

Yet Kamla's mastery over words extends far beyond the written word. She has also crafted several chants and songs that form the backbone of organisations such as Sangat and One Billion Rising. Famously, her chant Azadi gained popularity outside of activists and development workers when it was discussed in the context of a song of the same name in Zoya Akhter's film Gully Boy (2019). Kamla's cleverness and creativity is reflected in how the chant has evolved over the years—she has added verses to the chant to suit whatever situation she is in. For example, from starting out as only being about the patriarchy, the slogan took the shape of, "Azadi from helpless silence, azadi from violence, azadi from media vultures, azadi from nuclear thunder" during a conference in Beijing in 1995. In several interviews, Kamla herself has stated that, "Everything is so bloody interconnected," and so it is impossible to untangle the desire for freedom for women, from the freedom from caste, class, and other socioeconomic factors.

She wore all of her hats so effortlessly. It is a testament to how strongly she believed in the things she stood for, that she was able to carry them with her through whatever she did. Whether she was telling jokes (I still sometimes find myself flipping through Sangat's book of feminist jokes, Laughing Matters, by Kamla Bhasin and Bindia Thapar), singing songs, or just having an earnest conversation, Kamla's conviction and heart shone through.

I was lucky to get to know Kamla Bhasin at an age where I wasn't really able to comprehend the magnitude of her. For me, she was my phupu, Khushi Kabir's kind, raucously funny friend who was visiting from India. My earliest memory of her goes back to when Kamla had brought for me a bunch of adorably illustrated books—which I later learned she had written—including the Bangla translations of Ulti Sulti Meeto and Dhammak Dham.

These books quickly became my favourites at the time. Ulti Sulti Meeto definitely topped the list. It was about a silly young girl who did everything differently and how that's alright. Naturally, as a child, this was a special message. Growing up, however, I realised it was written for her daughter who had passed away. This was the magic that Kamla could weave, she could take the tragedies of life and turn it into something fun and beautiful for everyone else. She channeled this energy throughout her life, and even a few weeks before her passing she would share photos and videos of her singing and enjoying life and reminding us to do the same.

Kamla, though she may no longer be here among us, will live on through her work, her written word, as well as her chants, poems and songs, her kindness, her humour, and above all else, in the hearts of all who knew her.

Selima Sara Kabir is a research associate at the BRAC James P Grant School of Public Health, where she combines her love for reading, writing, and anthropological research.

For more book-related news and views, follow Daily Star Books on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn. Write to us at [email protected].

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments