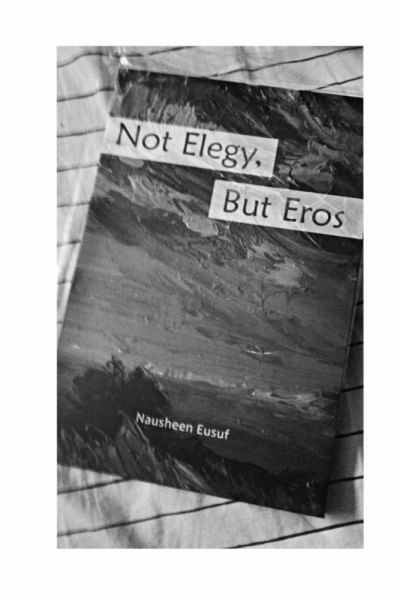

Not a Review, but Words of Heart: On Nausheen Eusuf's Not Elegy, But Eros

Life is an elegy, written by time. The instinct of life itself is elegiac, for it always reminds us of fragmentations and jouissance. Life reminds us of things that "are gone into a world of light," (as Eusuf writes in her poem, "Ubi Sunt"), stay "beyond the ignominy of the flesh" (in "Prayer to My Father"), or even "deliver us from our unfinished birth" (in"Prayer and Lament"). Nausheen Eusuf has measured life, not with a coffee spoon, but with a soul. And because of that, the Eros she explores is fluid, fragmented, at times too real, and at times, surreal. The Eros re-presents itself through her poetry as the Freudian 'unheimlich.' The presence (or the non-presence) of the uncanny flows like blood through the veins of her 48 poems catered in 6 different sections. Within those poems, she uses her transcendental poetic power over language and imagination as an essential trope to unravel the uncanny presence of absence, the life of the dead, and the words of the unspoken/unspeakable thoughts, through assortments of human's interactions with people, places, memories, objects, and time in a tone that constantly shifts from humor to pensiveness.

By negating the presence of elegy in the title of the book, Eusuf throws a new light to the notion of elegy as something uncanny. In the world she describes in her poems, the presence of elegy is so engraved that the mere thought of its absence would bring the feeling of the 'unheimlich.' Her poems are about loss and death, disappearance and absence, sufferings and anguishes: some portray these themes in personal level, while others take it to the macrocosmic level; some of the poems depict loss in context of individual body, while some point out the violence committed over a body (and bodies) for failing to comply with the hetero-normative views and the oppressive ideologies of a social body. The title of the book itself comes from a poem, which Eusuf has dedicated to a gender activist murdered in Dhaka in 2016. Another poem, titled, "A Final Embrace," is a strong statement on the death of the garment factory workers in 2013, while the poem, "Prayer and Lament" addresses the issue of death and murder caused by political violence in Bangladesh. In the poem, "How to Mourn the Dead," she pays tribute to those killed during the terrorist attack in a café in Dhaka, in 2016. "When they awake," Eusuf writes in that poem, "let us honor the spirits/who step lightly through/the garden of our disgrace."

She has written a series of poems on the issues of death of parents and/or of relationships and on the death of the 'self' in the sense of growth or change. The opening poem, "The Sorrows of the Dead" uses a somewhat Eliotesque imagery of a cat that comes back to the windowpanes of one's memory: "the three-legged cat/that comes to your porch at dusk to find/a bowl of milk," and Eusuf staunchly reminds us that we

"owe them that"—we owe that much to our bygone memories and our past pains. We do not need to write elegies on "the crap/one collects over a lifetime," or on the mother, who left all her worldly belongings to be sorted out by a humorous tour guide narrator of the poem, titled, "Musée des Beaux Morts"(it uncannily reminds me of Robert Browning's "My Last Duchess"), who draws the reader-voyeurist's attention from the dusted photo albums to the "gorgeous vintage/ Singer sewing machine that she bought/with her first month's salary in 1973/which hemmed many a sari and stitched/many a matching blouse and petticoat."

Not Elegy, But Eros is a powerhouse of smart and intelligent literary and critical references. Like a magnificent maestro, Eusuf vivaciously integrates allusions to poets, theorists, and artists, including the Old English poets, Goethe, Shakespeare, Roethke, Marvell, Shelley, Keats, Eliot, Yeats, Auden, Whitman, Freud, Paul de Man, Northrop Frye, Wallace Stevens, Jonathan Culler, Hitchcock, Salvador Dali—to name a few. The poem, titled "Ode to Apostrophe" can be read as her homage to the English poetry as a genre, in which she has playfully inferred to everyone from the poet of "The Wanderer" to that of "The Waste Land." In her rich world of imagery, days stumble "into the gorge of" Salvador Dali's "melting clocks" (in "The Days"), and a father suddenly wakes up from his dementia (in "Elegy for the Man She Married"), like one faulty King Lear and cries out, "where is my daughter?"In "Watching Hitchcock's Psycho," Eusuf sees Hitchcock's villain from a new perspective and forces us to look him in the eyes, making us conscious about our presence as absence as "both viewer & voyeur," and thus provoking us to acknowledge the uncanny mysteries regarding the presence in/as absence of Self and God, and the ontology of being and nothingness (in "Ode to Apostrophe").

Life is an elegy, written by time, but death is not elegiac at all; it is the very instinct of life's lived and living force. Death is a presence that can only happen through absence and then is remembered as a presence in past. The absence and presence in Death is "the rift/in the yarn that unravels the whole" (in "Poetry"). Eusuf therefore bids "happy endings to grim tales" (in "Lullaby"), hoping to "transmute/the known facts into the new and unknown" (in "The Sample is Shining"), "where nothing happens, but something abides" (in "Ode to the Slow Life") so that we are not offended (as the speaker in "The Overall" notes) when "it's all over," and

"we return, meek and listless,

to that great beyond, the earth's over-all

translucent pitch, its all-devouring darkness."

Fayeza Hasanat is an author, translator, and educator. She writes regularly for The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments