Who Defines Obscenity?

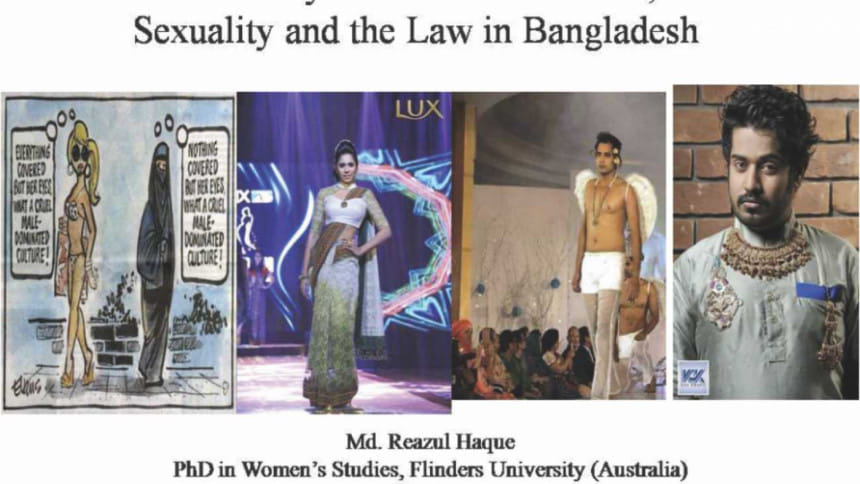

Recently, the news of a Dhaka University (DU) teacher's suspension – following claims from some of his Masters students that he showed “obscene materials” in his Gender and Development class – made the rounds on social media. The DU authorities temporarily suspended Development Studies Professor Dr Md Reazul Haque over the allegation. The slides that stirred this debate depict illustrations and pictures which critique gender-insensitive behaviour and public policies.

This incident naturally raised important questions: What exactly was the objectionable content of the course? How do we even define obscenity in study materials, particularly in disciplines like Gender and Development Studies?

The allegation that the materials taught in Dr Haque's class were “obscene” reveals a deep-rooted anxiety and discomfort to discuss issues related to gender and sexuality. Sexuality, since long, has been deemed as something to be discussed in hushed voices, behind closed doors – something too inappropriate, to be discussed openly in a class. Even if it's in a room full of adults who should be able to confront these issues in a critical and constructive manner.

“Teaching gender and development studies will inevitably require the instructors to bring up 'sensitive' topics, ranging from sexual orientation to transgender movements, from the history of sexual norms to queer theory and gender identity and gender biases,” says Dr Sadeka Halim, Professor, Department of Sociology, Dhaka University, and former information commissioner. “The more I teach gender studies in classrooms, the more I realise that there is still a tremendous amount of taboo around sexuality and the female body.”

What surprised Dr Haque is that that none of the 15 students raised any objections during the classes about the audiovisuals and overall course material. In fact, throughout his career, while teaching subjects like gender and development, social inclusion or feminist research methodologies, he was required to bring up issues that we generally don't talk about in public. In 2015, he published his book, Voices from the Edge: Justice, Agency and the Plight of Floating Sex Workers in Dhaka, Bangladesh, which was applauded by gender experts in the country.

Dr Haque shares his confusion regarding his students' reactions. “Many women are physically and sexually harassed at home - sure, we all know that. But when I show pictures that show bruises on the exposed parts of the female body – that suddenly becomes obscenity?” questions Dr Haque. “If I talk about rape culture or body politics of the Hijra community in modern Asia in my classroom, how can it be considered vulgar? If my fellow professor from Population Science chooses his PhD thesis on 'Homosexuality, HIV and Stigma', would we consider that to be inappropriate and obscene as well?”

If we consider these issues “obscene”, public discussions on issues like sexuality, rape, and reproductive health will continue to be vague and deceptive. And what constitutes obscene, anyway, and according to whom? As Mahmudul H Sumon, Associate Professor, Department of Anthropology, Jahangirnagar University, argues, “The question of obscenity is a subjective and relative one. I would rather ask whether the content shown in Dr Reaz's classes was relevant or not, and honestly, I think it was.”

Sumon believes that such censorship will also make it difficult for academics in the fields of sociology, anthropology, gender and development to design a relevant curriculum. He states, “Dr Haque's incident also instils fear in other professors teaching similar kinds of material. In fact, such censorship questions the validity of having these sorts of disciplines in our academia.”

Sumon believes that through the introduction of subjects like Gender Studies in the curriculum, we have finally accepted 'sexuality' as something that can be talked about publicly in the classroom. “It's imperative for us to be able to hold on to that,” he says. “Subjects like these help us to constantly think about positive transformation for the future while making us question the age-old beliefs, customs and traditions in perpetuating gender discrimination. This kind of discipline is a must for the younger generation to recognise the manifestations of gender inequality. It is time to place gender at the centre of our education agenda.”

Labelling course content as “obscene” and “vulgar” will hinder the creation of an inclusive environment in the classrooms and discourage free thinking, believes Dr Halim. “After Dr Haque's incident, other faculty teaching similar subjects will be in a persistent fear of being watched and judged for what they teach in the classrooms,” she adds.

Unfortunately, starting from a young age in school we are taught to shy away from topics that society considers to be “sensitive” and “controversial” no matter how important they may be. Thus, our natural reaction is to be “offended” when we are confronted with such issues. It is common for teachers to approach sexuality and reproductive health from a superficial standpoint, without recognising the importance of conducting discussions with students in a professional and educational manner. Incidents like the suspension of the university teacher will thereby surely further weaken the confidence of facilitators to talk about these issues that are crucial to understanding society, people and our identities.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments