Demolished in plain sight

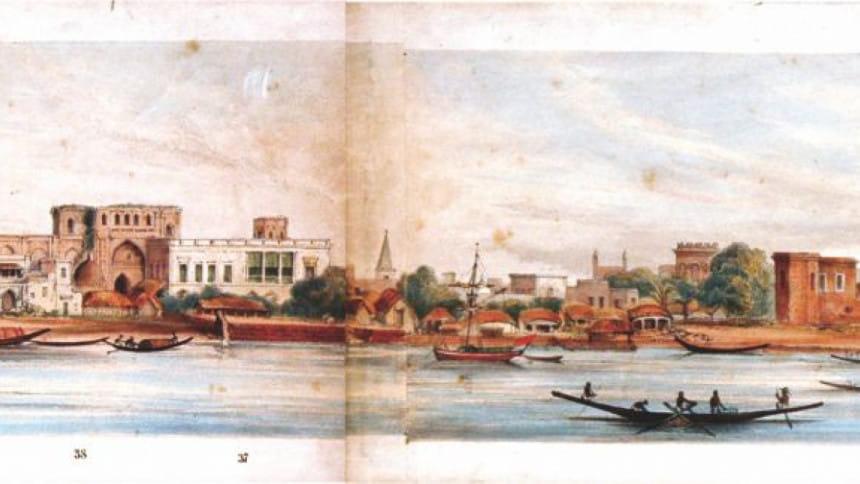

Puran Dhaka, even today, possesses enough heritage treasures to be the envy of many cities known for their historic character. Unfortunately, over the last decade, despite earnest efforts of civil society, activists and the media, there has been a steady increase in the erosion of its historic urban fabric. In fact in many places, whole neighbourhoods have been cleared up—today not a single old building can be found there.

The lack of awareness about the significance of cultural heritage is one cause but that is hardly the only one. The absence of any support mechanism for the preservation of heritage properties has pushed many private property owners to resort to replacing old buildings with multi-storeyed apartment buildings to take care of their immediate financial and housing needs. Over the last decade, they thoroughly changed the urban fabric of the old town.

To understand real estate development in Old Dhaka, it is necessary to understand who these property owners are. A large share of the properties listed as vested properties were actually illegally acquired by land grabbers who exploited the situation. Taking advantage of this weak statutory framework, real estate developers moved in for the kill.

The occupation began in 1947 when the city experienced a massive demographic change, as a majority of the Hindu population migrated to India while about 200,000 Muslims from India settled in Dhaka. The city's population practically doubled during this period. Migrant Muslims settled in the neighbourhoods belonging to the Hindu community. The vacant grand residences and mansions of Hindu elites were turned into multi-family dwellings, such as tenement housing, to provide accommodation for the migrants; of course many properties were also swapped by wealthy Muslims who left their properties in India. This change had a far-reaching impact on Puran Dhaka.

The next two or three decades till the '70s saw a gradual but steady change in the pre-partition Muslim neighbourhoods. With the abolition of the zamindar system in the mid-1950s, the elite mohallas gradually lost their shine, and eventually saw redevelopment on their properties. Puran Dhaka was sliding back into despair. Post-1971, as the population of the city increased very rapidly, the stress of migration was also felt in the old neighbourhoods of Puran Dhaka.

Although there appears to be a causal link in the whole process, the problems and failures of the concerned to take any effective steps to stem this degeneration of the traditional urban fabric seems to have been orchestrated in order to achieve an overarching goal of transforming Puran Dhaka into a high-density, high-rise development.

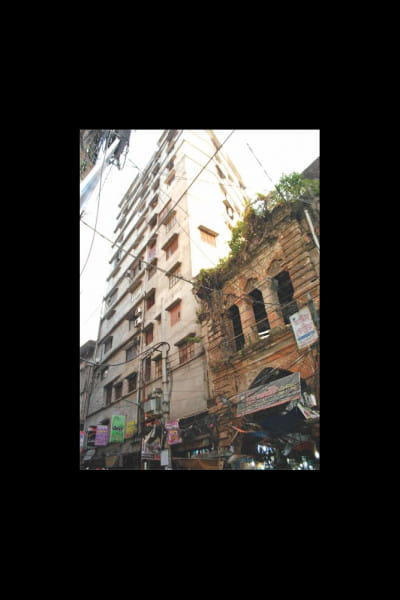

Today, it is not just that buildings are straight-up being broken down. Take a closer look into the wiping out of Puran Dhaka and you'll find that besides the demolition of old monuments, there are quite a few other ways of destroying the tradition at urban fabric of the old town. High-rise buildings built with incompatible construction materials can have quite a negative impact on the street.

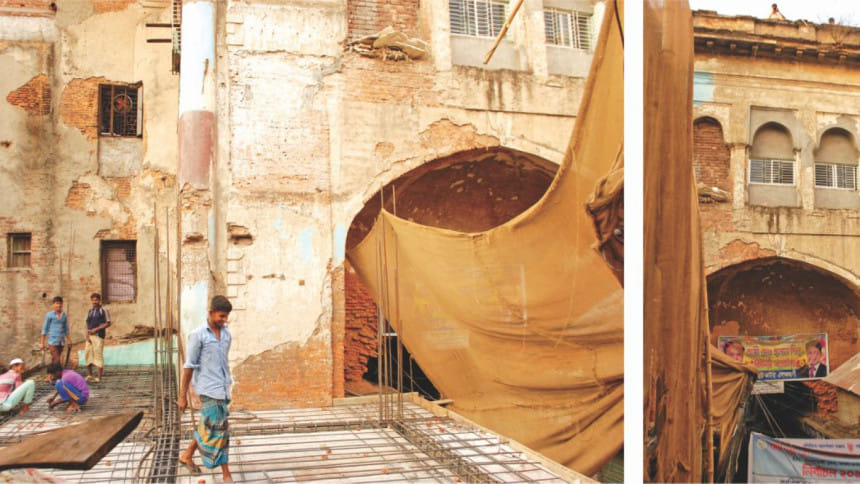

In many cases, we find vertical extensions on old buildings, where the adding of one or two floors is a very common practice. However, they usually have a telling effect on the façade of the building. In case of streets, which are designated as heritage sites as a whole, the extra height can also have serious negative effects on the skyline of the area, thereby its heritage value. Other times, the extension is built horizontally either on the back side or the front side of the heritage buildings, obscuring the façade of the heritage buildings as a result. Even if these extensions are just patchwork additions, they can have a very negative effect on the heritage value of the site. It is a common practice in Puran Dhaka to build structures in the open around a building. A multi-storeyed building constructed in the backyard of a heritage site can actually look quite disrupting, while a multi-storeyed structure built in front of heritage building is often constructed solely to hide it and eventually demolish it.

In certain areas it is quite obvious the construction of high-rise structures is being deliberately done in order to promote similar developments along that road or line. This phenomenon is pursued without any regard for heritage properties. Examples of this can be seen in the Chawkbazar area and Bikrampur Garden City in Islampur. In certain neighbourhoods of Puran Dhaka it is quite obvious that when the demolition takes place they actually focus on certain areas and then gradually get rid of all the old buildings there. A case in point is Amligola. Only in 2007, there were around 60-70 old buildings on JN Saha street. Unfortunately, after pursuing aggressive demolition of heritage buildings over the last decade, the street has been stripped of its heritage properties by the dozens. We have seen similar examples in the case of Golokpal Lane, Bakshi Bazar, Orphanage Road and Nawabpur Road among others.

Often the destruction of the urban fabric appears less significant than the construction of multi-storeyed buildings that destroy the skyline. On the north-eastern corner of Boro Katra, an 18-storeyed building has been constructed at a handshaking distance. To take advantage of the building construction rules regarding Floor Area Ratio, almost a dozen smaller plots have been consolidated to form a single large property that overshadows the magnificence of Boro Katra. This is being touted as a success story by RAJUK. Similar structures can be seen at the Mitford Road-Imamganj intersection. Multi-storeyed buildings within the buffer zone of a historic building can actually compromise the heritage value of the monument and the campaign to designate the Boro Katra as a world heritage site in the long run is affected.

Much of this destruction has been the result of sheer negligence and failure of policymakers, concerned government agencies and regulatory bodies. The failure of agencies such as the Department of Archaeology, mandated to preserve the heritage assets of our country, has resulted in steady loss. On the other hand, the unwillingness of regulatory bodies like RAJUK to intervene in case of violations has created major stress on the whole urban fabric of the old town, as a result of which the historic city is fast losing its identity. Towers being built within the courtyard of Choto Katra not only reveals the incompetence of the concerned government agencies—their reluctance to enforce the laws for the protection of monument can be seen as tacit support for the perpetrators of this criminal offence. Topping all that, a series of major policy decisions by the Dhaka South City Corporation, the most important people's representative body for the old town, are having serious negative impacts on the heritage assets and historic urban fabric of Puran Dhaka.

Taimur Islam is the Chief Executive of Urban Study Group.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments