Sugar and Spice and Everything Not-So-Nice

We have witnessed Meena trying to equalise her domestic workload by swapping roles with Raju. Meena probably takes pride in knowing that at present Bangladesh is the most gender-equal country in South Asia, closing 71.9 percent of its gender gap. In 2019, an estimated 36.37 percent of women constituted the labour force in Bangladesh, hitting an all-time high. These numbers are worth celebrating, although we should ask if they reflect greater equality in household work sharing.

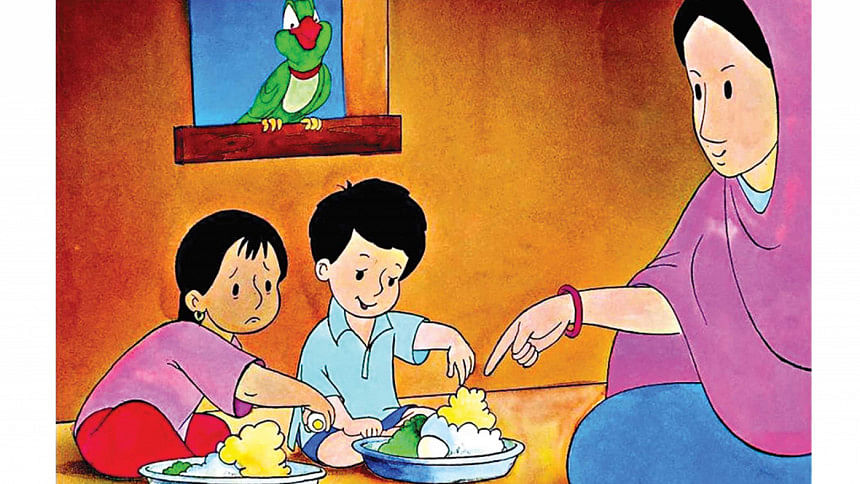

Let's look at our dinner table today. Have practices around our dinner table changed much? Or, does subtle sexism still creep into our communication and convention in our dinner tables unconsciously?

In most households, women prepare the table and invite family members to dine. While they serve dishes to everyone, their plates remain the last ones in line. Women serve more and are comparatively served less in daily dining. The plates are also left to be picked up by women after everyone is done with their meals. Male participation in all this remains voluntary, often saying that it is women's work. The whole process harbours misogyny as well as toxic masculinity.

What's wrong with doing household chores? The problem is not in doing the chores rather in the unfair and unequal participation, and in romanticising it in the name of affection, hospitality, and culture towards one specific gender. Women are not the sole flag bearer of affection, nor do they have to adhere to practices that seem to cost them more. The problem also lies in the presumed hierarchy of men and in behaviour that discourages burden-sharing with women in our families.

Most importantly, the problem lies in its banality. We forget sexism starts small, in intimate spaces, before it spreads like wildfire in our society. We condemn sexism, misogyny, and mistreatment towards women in the public sphere, but do not evaluate or question our participation in these in the private sphere. Largely unaware, many of us tend to hold ourselves in a morally superior position and mask day-to-day subtle sexism behind affection for women in our lives.

The key to addressing this inequality lies in behavioural changes. Behavioural changes happen slowly and gradually, where acknowledging the problem remains the first step. Without recognising the unfair, sexist and imposing nature of the practices, the risk of sustaining and reproducing them through generations remains. Breaking this cycle requires greater sensitisation, along with stepping out of designated gender roles.

In pondering viable ways to address misogyny and sexism that plague our lives, we often wait for grand opportunities. This time, let's start small by trying to identify the pattern of our behaviours. We rectify this by participating. Irrespective of our gender, we serve the one who has served us all along, we ask them if they need more, we take our plates to the kitchen and wash them. Because the most crucial of changes start at home.

Erina Mahmud and Nalifa Mehelin are respectively outgoing and incoming MSc Candidates at London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments