A dangerous suggestion

As a people, we have a tendency to be enamoured with the present political realities and treat the past with utter disdain. Even worse, we want to rewrite it, thus overvaluing the present and throwing the past into the bin. That is why we don't learn from the past and repeat our mistakes. Our history is full of this. It is a reflection of both our emotional nature and superficial knowledge base. One result of this is that we seldom engage in debates but instead mostly have rhetorical exchanges in which our capacity to shout holds sway over our capacity to reason.

A more cynical view would be that we desperately want to harvest the political advantages that followed the power vacuum left by the ouster of the past regime, caring neither for the truth nor for morality, values, and national interest. Thus, we push our self-serving narrative using the political power of the day. The fact that attempts to tailor the past do not stand the test of time—what better proof could there be than Hasina's fall?—never seems to have dawned on us. So, we follow the same route and end up in the same gutter.

The rhetoric of those in the driving seat is that many things about the past, especially after '71, have been a big mistake or highly distorted and need to be re-examined. If it is an intellectual journey, then we can all benefit from it. But if it is a political project, then it will be self-destructive except for those who still don't believe in Bangladesh. Some of the present-day narrators consider themselves as the custodian of the "truth", and any attempt to question them is turned around as trying to resurrect the past, thus discouraging independent thinking, critical assessment, and enquiring habits.

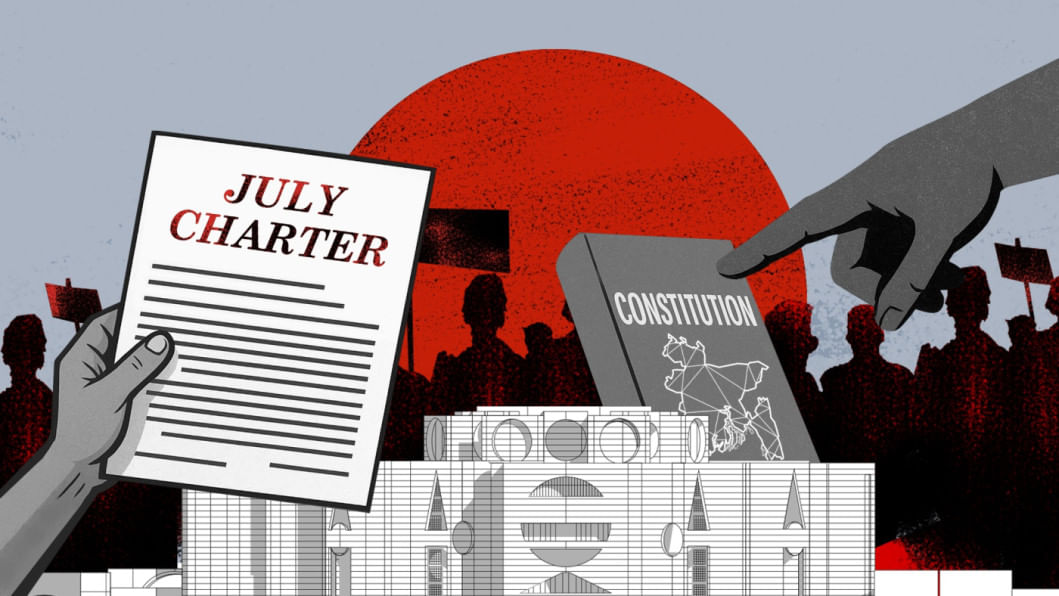

One example of unjustifiably denigrating the past is the way our present constitution is being discussed and treated. The narrative is that the constitution gave rise to fascism and hence it has to be replaced. An alternative view could be that the rise of Hasina's dictatorship and her arbitrary use and abuse of power were not intrinsic to the constitution that we got in 1973. Rather, it was the misuse of certain parts of the constitution's provisions that destroyed its democratic structure. The separation of powers between the legislative, the judiciary, and the executive—which was well designed in our constitution—was distorted over time. Powerful leaders like Bangabandhu, Ziaur Rahman, HM Ershad, Khaleda Zia, and Sheikh Hasina all used their parliamentary majority and other means to expand the authority and power of the executive, which over time throttled both the legislature and the judiciary.

What went wrong is due to the political culture practised by our political parties, many of whom are now the authors of the July Charter. It is they who, when in power, used their majority to curb the system of "checks and balances." If we examine the last 35 years of parliamentary democracy, we see that both the BNP and the AL—parties that ruled during this period—never assisted in strengthening the judiciary or the Jatiya Sangsad, but were enthusiastic about strengthening the executive branch. The role of the majority party in the House, the opposition, and the farcical role of the House Speaker all contributed to turning a democratic constitution into a legal framework for dictatorial regimes. It is also the result of the abuse of the parliamentary procedures facilitated by the frequent walkouts, boycotts and finally resignation from the parliament that left the ruling party an unchallenged and open field to do as they pleased. Even the standing committees did not play their roles of holding the government to account because of the overwhelming power of the prime minister, who was also the leader of the House and the party chief. Every time one party or its coalition got a huge majority, they misused it and amended or misinterpreted the constitution to suit their power-hungry agenda.

The first and perhaps the saddest example, which brought about a total distortion of the constitution, is the introduction of the one-party system, namely BAKSAL, that transformed the parliamentary system to a presidential one, banned all political parties and made Bangladesh a one-party state, closed down all private newspapers and kept alive four nationalised ones, and took away all the democratic values of the constitution. All these, it is said, were determined in less than 30 minutes.

Then came the Fifth Amendment introduced by President Ziaur Rahman that validated all actions and constitutional changes from August 15, 1975 to April 9, 1979, including the Indemnity Act that gave constitutional protection to self-professed killers, thereby destroying the "moral" value of this sacred document. Here was another grave example of how the executive branch made a mockery of the whole constitution and respect for the legal system.

Then there were other amendments brought about through actions that did not fulfil what is known as the "constitutional process." The ruling party ordered it and the majority of MPs carried it out. One exception was the caretaker government whose introduction was bipartisan but, regrettably, its annulment was totally partisan and aimed at manipulating elections that we saw in 2014, 2018 and 2024.

The National Consensus Commission (NCC) has worked hard to prepare a July Charter, including a series of suggestions for amendments to our Constitution. An in-depth comment on their work will follow later. Our piece today will discuss two provisions of the NCC report's last segment titled "Pledge to implement the July Charter."

First, we fully agree that all political parties must make an irrevocable pledge that, as and when they are elected to the coming parliament, they will work together to amend the constitution and incorporate the provisions contained in the July Charter. Without the parliament voting these amendments into the constitution, there is no other process that can legitimise the progress made so far. Hence, the vital importance of the "pledge."

Below we illustrate the problems that arise from the provisions made in Pledges no. 2 and no. 4 (reproduced below) that we consider to go against all democratic spirit and stand out as a repetition of the mistakes of the past.

Pledge no. 2 reads: "The people are the owners of this state; their will is the supreme law, and in a democratic system, the people's will is reflected and established through political parties. Therefore, we, the political parties and alliances, having collectively and through long discussions adopted the 'July National Charter 2025' as the clear and supreme expression of the people's will, shall ensure the incorporation of all provisions, policies, and decisions of this Charter into the Constitution; and if there is anything contradictory in the existing Constitution or any other law, then in that case the provisions/declaration/recommendations of this Charter shall prevail."

Pledge no. 4 reads: "Every provision, declaration, and recommendation of the 'July National Charter 2025' shall be considered constitutionally and legally enforceable; therefore, its validity, necessity, or matters related to its issuance shall not be questioned in any court." (The original text of both paras is in Bangla; the English translation is ours).

Let's take the opening lines of Pledge 2. "People are owners of the state"—yes. "Their will is supreme law"—yes. "and in a democratic system people's will is reflected and established through political parties". Well, here start the problems.

A total of 30 political parties participated in the consensus dialogue in the second round. As many as 11 of them are not yet registered. Four parties have obtained registration after the uprising. So, these 15 parties (11+4) have never participated in any election. So, nothing definite can be said about how many votes they would get. They may sweep the polls or get muted support. We don't know, and hence we cannot presume. In the 2008 elections, six political parties got zero votes.

In a democracy, every cluster of citizens has the right to form political parties and carry on their activities as long as they are compliant with the law. They may represent the best of ideas in the world, but unless they have faced the test of public support—through elections—they cannot be said to represent the people in general.

Then there are new parties, the most famous of which is the National Citizen Party, the party born out of the July-August uprising. The whole nation totally supported the student-led movement against the dictatorial regime of Sheikh Hasina. A section of student leaders then formed a political party with their own ideology and national goals. But how much public support they presently enjoy cannot be judged by their brilliant success in toppling Sheikh Hasina.

Let's focus on the 2008 election again. It is considered to have fulfilled most of the criteria of a free and fair election. The percentage of votes were: AL 48 percent, BNP 32.50 percent, Jatiya Party 7.04 percent, Jamaat 4.70 percent, and independent 2.98 percent. These four parties, including independents, got a total of 95.22 percent votes. Of the above four parties, two are out of the present-day scene. The remaining BNP, Jamaat and independent candidates add up to 40.18 percent of the votes. So, the consensus reached by the NCC reflects the views of only 40.18 percent of voters participating in the 2008 elections. These are not conclusive facts but suggestive ones to help us decide for the future.

However, there is one severe criticism of the NCC that cannot be and should not be ignored for the sake of democracy, inclusiveness and justice. The issue of women. Women represent about 50 percent of our population and nearly 50 percent of voters. Yet they had almost no voice in the formulation of such a historic document, the July Charter, whose provisions are going to be incorporated in our constitution and will prevail over any other existing ones. Ignoring women voters is a shame and a moral "crime" that NCC will always have to live with. How can that be considered a democratic basis for consensus?

Parties like BNP have millions of women voters, yet they did not consider it fair to take a single woman-member in their own team. If a 47-year-old political party like BNP does not consider it worthwhile to ensure women's representation, then how reflective is the NCC report in terms of women's rights as voters?

Pledge 4 says in conclusion that "its validity, necessity, or matters related to its issuance shall not be questioned in any court."

We take strong objection to this Pledge. In a democracy, how can any provision of a constitution be outside the purview of the judiciary? It is the most undemocratic, dictatorial and oppressive provision that can be. Once again, we are putting the executive branch above the judiciary and the legislative branches. As mentioned in the beginning, we learn very little from the past and hence repeat it ad infinitum. Interestingly, the ousted PM introduced Article 7B by which she made the "Basic provision of the constitution," making up one-third of the constitution, non-amendable. Why are we following her footsteps?

Constitutions, by definition, are products of people's will, which changes over time as society and civilisation advance. Yes, we have a history of misusing the "amending process" but making any part of a constitution "unamendable" is a dangerous and self-defeating option.

We now have a magnificent chance to strengthen democracy and all its institutions. Let's not miss it. Sadly, indications are that we are.

Mahfuz Anam is the editor and publisher of The Daily Star.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments