Who pays when the roads are blocked?

Every time political or ceremonial events take over the streets in Bangladesh, it is the ordinary citizens, "the mango people," who silently pay the price. Small traders, informal workers, and roadside vendors are the first to suffer when traffic comes to a halt, deliveries are missed, and perishable goods go bad.

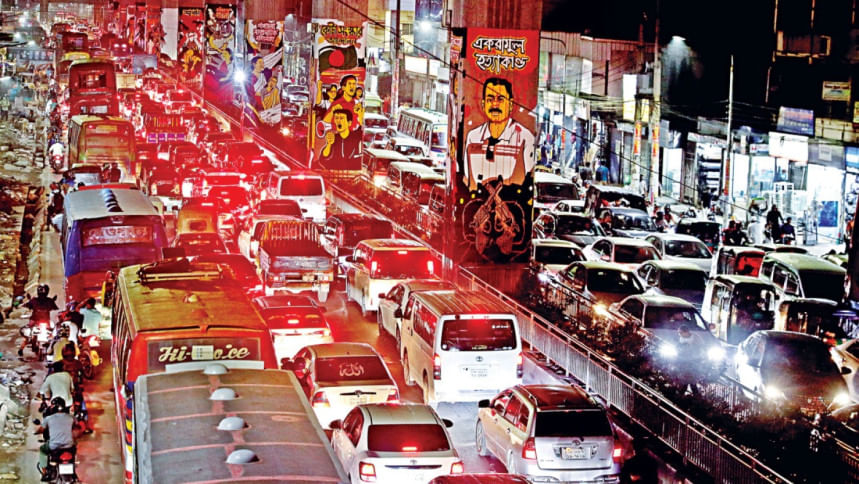

The economic cost of road blockades is not an abstract concern. It plays out visibly, as it did on August 6, when Dhaka was brought to a near standstill by celebratory processions and street programmes. While supporters of political parties waved flags and loudspeakers blared, the city's arteries choked. Delivery vans were stuck for hours, online orders were cancelled, office-goers were stranded, and many daily earners—who often survive on a few hundred takas a day—went home empty-handed. The irony is that even when there is no political unrest, the culture of blocking roads for rallies and commemorations has the same suffocating effect on commuters, small business owners, and informal workers.

Over 78 lakh SMEs in Bangladesh employ more than two crore people and account for about 27 percent of the country's GDP. These livelihoods are often dependent on road transport. A half-day of blocked streets means halted deliveries, lost inventory, and cancelled sales, especially for perishable goods like fruits, fish, and dairy.

In 2023, an Al Jazeera report cited the Federation of Bangladesh Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FBCCI), which stated that the ongoing blockades were causing Bangladesh's economy to lose Tk 6,500 crore per day. This trend persists to this day. And the greatest burden of this loss is borne by the poor, not really by the large corporations or organisers of political parties.

The situation worsens for small businesses due to systemic and structural unfairness. Generally, large businesses can adapt as they have warehouses and can use alternate routes. The wealthy can stay home or shift to online services. But the "mango people" do not have that luxury. For them, every hour of gridlock is a step closer to poverty. And when gridlock comes not just from political unrest but from celebrations and rallies, the message is even clearer: their time, work, and survival are dispensable.

This trend must be reversed. I think the following steps will make a difference: i) creating emergency movement protocols; ii) ensuring stricter regulation of road occupation; iii) protecting informal livelihoods; and iv) enforcing transport discipline. Essential and perishable goods must be allowed passage during all major events, closures, or celebrations, and rallies must be time-bound and limited in scope. Such events should be held in designated zones away from economic corridors. Furthermore, urban mobility plans should ensure that no single event can paralyse the capital's transport for hours.

August 6 was just the latest example—but protests, blockades and other street programmes are a recurring nightmare for small traders and workers. These people do not gain anything from symbolism, and yet they lose the most. If we want an inclusive and just Bangladesh, the "mango people" must be given the freedom to move, to trade, and to earn—no less than anyone else.

Dr Mohammad Naveed Ahmed is managing director of Miyako Appliance Limited, Bangladesh, adjunct associate professor at Independent University Bangladesh, and joint convenor at the Dhaka Chamber of Commerce and Industries.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments