Of tea, tantrums, and Tudor theatre

If history is, as philosopher George Santayana warned, something we are doomed to repeat when we forget it, then Bangladesh's Awami dynasty has taken that wisdom and staged it as a family-friendly farce somewhere between EastEnders and a Shakespearean tragedy. Or is it a Netflix political satire? It's getting hard to tell.

This week, London witnessed not just the drizzle of summer rain but the awkward drizzle of dynastic dysfunction, imported directly from Dhaka—wrapped in diplomatic lace, then promptly stomped on with protest boots.

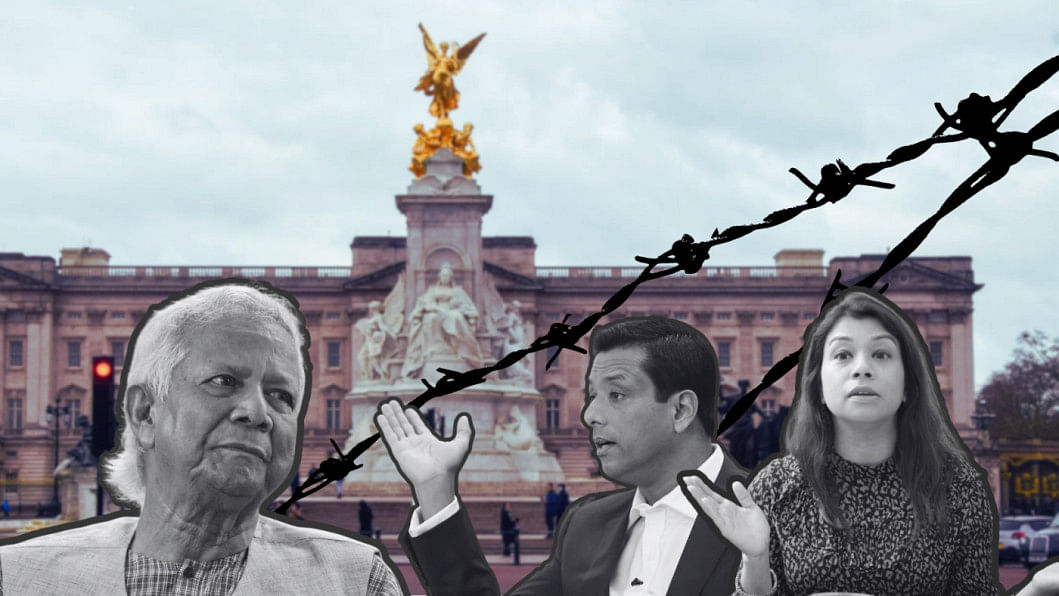

Prof Muhammad Yunus, Nobel laureate and currently the chief adviser of Bangladesh's interim government. A man whose résumé makes most heads of state look like part-time interns. Invited by King Charles III to receive the inaugural Harmony Award—an honour meant for those rare few who have nudged humanity towards peace—Yunus's trip to the UK should have been a textbook case in soft power diplomacy.

But then came the black flags. And the Facebook posts. And the tea.

Because what is a grand statesman's moment without a family-led circus determined to hijack the stage?

Sajeeb Wazed Joy, digital enthusiast, dynastic heir, and part-time Facebook warrior, announced his parallel visit to London, accompanied by a cast of European Awami League loyalists coming in for a protest outside St James's Palace. Dressed in black flags and righteous fury, they shouted slogans that made more sense in Motijheel than Mayfair.

Not to be outdone, Joy's cousin Tulip Siddiq, Labour MP and niece of Bangladesh's ousted Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, emerged from the fog with a peculiar gesture: an informal invitation to Prof Yunus for tea at the House of Commons. Because when your family accuses a man of state capture, the logical next step is a cosy sit-down over Earl Grey.

Tulip's note was as tone-deaf as it was self-serving. No formal address. No reference to Prof Yunus's interim role. Just a breezy Britishness laced with Bangalee entitlement. As if this were a tiff over stolen biscuits at a school reunion and not an institutional breakdown between a Nobel laureate and a family accused of looting state coffers.

And then came the irony's crown jewel: Joy, Tulip's cousin and Hasina's son, emerged on Facebook hours later to declare Yunus a "dictator" and warning UK officials not to meet him. One cousin offers tea. The other offers threats.

This contradictory choreography—one part charm offensive, one part tantrum—reveals not a family at odds but a coordinated campaign cloaked in contradiction. A two-pronged PR strategy: Tulip softens, Joy sharpens. One feigns civility, the other screams conspiracy.

The playwright Harold Pinter once said, "There are no hard distinctions between what is real and what is unreal, nor between what is true and what is false." He could have been describing the Awami League's current information strategy.

Tulip, cast as the rational moderate, is trying to distance herself from the corruption scandals circling her family. But a quick look at the public records exposes the PR bubble.

She claims no property in Bangladesh. The Anti-Corruption Commission, however, lists her as co-owner of prime real estate in Purbachal and Gulshan. Properties that require a Bangladeshi national ID, a taxpayer identification number, and a network of bureaucratic approvals only available to—wait for it—insiders.

Then there's the small matter of Special Security Force (SSF) protection, a benefit under the Father of the Nation Family Members' Security Act, 2009. Tulip has neither disavowed nor declined this privilege, funded by the very taxpayers now watching her mock due process from across the globe.

But entitlement, as political psychologist Dr Drew Westen argues, is "the anaesthesia of the powerful—it numbs one to the suffering of others while keeping alive the illusion of victimhood."

Tulip's new storyline, crafted for British media paints her as a victim of a "smear campaign." Yet, she enjoyed the protection of Bangladesh's state machinery for years without ever questioning its abuses. She remained notably silent during enforced disappearances, political repression, and the infamous Digital Security Act's reign of fear.

Tulip is neither rebel nor reformer. She's a symptom of dynastic privilege masquerading as democratic engagement.

The House of Commons is not a therapy couch for political heirs trying to whitewash their familial baggage. Nor is it a press gallery for proxy wars over legitimacy.

The British establishment must tread carefully. Prof Yunus visited London not as a freelancer of democracy but as the recognised transitional figure in Bangladesh, endorsed internationally and formally received by King Charles III. To allow his visit to be hijacked by political agitators related by blood but severed by credibility would be a farcical betrayal of everything the British system supposedly upholds.

Tulip's antics, Joy's outbursts, and their family's fragile grip on the truth all boil down to a single pathology: they cannot bear the idea that Bangladesh might now stand on its own, led not by blood but by merit.

As author George Orwell once wrote in Animal Farm, "All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others." The Awami League's "royal" family has long believed itself to be that "more equal" kind. But democracy has a habit of correcting course, however messy the process.

Prof Yunus's visit, beyond its ceremonial significance, marks a symbolic shift. From rule by surname to rule by substance. From dynasties to dignity.

And if Tulip and Joy want to continue their cross-continental roadshow, the least they can do is rehearse the same script.

H.M. Nazmul Alam is an academic, journalist, and political analyst. He can be reached at [email protected].

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments