How law was manoeuvred for human rights violations during July uprising

The mass uprising in July-August 2024 primarily evolved to reform the unjust and discriminatory quota system in public employment, which later turned into a nation-awakening anti-discrimination movement. The march for equality and zero discrimination, led by students and joined by masses from all walks of society, was unlawfully attacked and suppressed by law enforcers of the then government. The massive and violent crackdown led to serious human rights violations, including crimes against humanity and mass killings. As the UN fact-finding report estimates, the unlawful use of lethal weapons by law enforcers and unjustified shoot-on-sight order killed as many as 1,400 people, including many children, and injured thousands.

During the movement, thousands of student protesters were arbitrarily and unlawfully detained and tortured, violating the right to liberty of the person and due process guaranteed under the constitution and international human rights laws. Apart from mass killing and arbitrary detentions, the imposition of internet shutdowns violated civil and political rights, including the right to freedom of expression, information, and peaceful assembly. In all cases of human rights violations, either the law was used to justify the cause in the name of "national security," "use of force as self-defence," and "public interest," or it played a complicit role in weaponising state mechanisms for oppression, harassment, and torture.

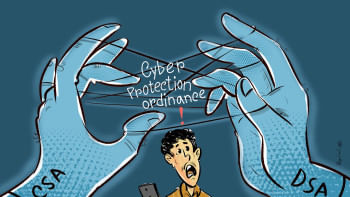

The July uprising also exposed how law has been deeply manoeuvred as a tool to commit human rights violations. The past government promulgated some draconian and repressive laws that helped sustain the regime at the cost of recurring human rights violations. The Digital Security Act (DSA), which was a footprint of an earlier repressive provision of Section 57 of the ICT Act, enabled digital authoritarianism in Bangladesh, leading to numerous arrests of rights activists, journalists, human rights defenders, students, and even ordinary citizens. A study by the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS) found that under the DSA, 7,001 cases were filed against 21,867 individuals between October 8, 2018 and January 31, 2023. This repressive law was designed in such a way that its misuse was not required—the very use of the law enabled harassment, intimidation, and torture, silencing dissent.

The overly broad and vague provisions in the digital laws have provided unchecked power to the law enforcement authorities, allowing them to weaponise the law by detaining individuals on mere suspicion without a warrant. This provision was indiscriminately used during the uprising. The legally empowered, unfettered authorities of state agencies were extensively used to block content and data from digital spheres and social media, violating due process as per human rights standards.

The intended outcome of the digital laws was a culture of fear, intimidation, and self-censorship. These laws, in their crafting and application, prioritised political agendas over safeguarding digital rights. While human rights in the digital spheres are constantly evolving, repressive digital laws have helped expand authoritarian rule by criminalising free speech, increasing surveillance, and silencing detractors.

Defamation laws were also aggressively used during the past regime to curtail freedom of expression and criminalise any sort of criticism. The colonial penal laws, the Contempt of Courts Act, and the DSA that criminalised defamation were extensively applied. Filing a series of cases for a single alleged defamation against media outlets, journalists, editors, and activists was common in the past regime. The Code of Criminal Procedure requires that only an aggrieved person can file a defamation case, but this provision was routinely violated in defamation cases. In most cases, members of the ruling party filed defamation cases as aggrieved persons when anyone criticised their political leader.

The complicit role of law in human rights violations was armoured by institutional inability and weakness. For example, the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) was legally barred from directly investigating human rights violations committed by the security forces. This legal bar, coupled with its lack of independence influenced by political imperatives, made this watchdog body a toothless and ineffective institution.

Notably, even though more than eight months have passed since the resignation of the NHRC's chairman and members in November last year, a new commission has yet to be formed. The interim government had the opportunity to remove the legal barriers facing the NHRC, enhance its institutional capacity, and establish a strong and effective commission through a transparent, politically neutral process. However, that has not been done yet.

The enabling role of law in facilitating human rights violations was also perpetuated by the widespread failure in enforcing laws. Poor law enforcement helps promote a culture of impunity for the abusers, where law becomes a tool of oppression rather than protection. Laws are made to protect human rights and ensure justice; however, when laws are drafted with vague provisions, poorly and selectively applied, or deliberately used to justify arbitrary detention, undermining fundamental freedoms and aiding discriminatory practices, then the legal system may turn into an enabler for human rights violations. This becomes fatal in a country that suffers from a fragile rule of law, limited judicial independence, and democratic deficit.

The July uprising enabled a renewed opportunity to embark on transformative and systemic legal reforms necessary for a re-envisioned Bangladesh. The ongoing reform agenda, though it sounds transformative in words, remains elusive in reality. The collective voices and aspirations of the masses to challenge the entrenched power structures, as manifested in the July uprising, by redefining the social contract between the state and its people, are not adequately articulated in the reform agenda. The people's uprising gave us a rare opportunity to re-examine the foundational principles of governance, justice, and accountability, and reimagine our legal and political landscape that serves the people, not the powerful. This opportunity should not be wasted.

Mohammad Golam Sarwar, a Chevening and Commonwealth scholar, is PhD researcher in law and alternative development at SOAS, University of London. He is also an assistant professor (on study leave) in the Department of Law at the University of Dhaka.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments