How to judge the Election Commission’s performance

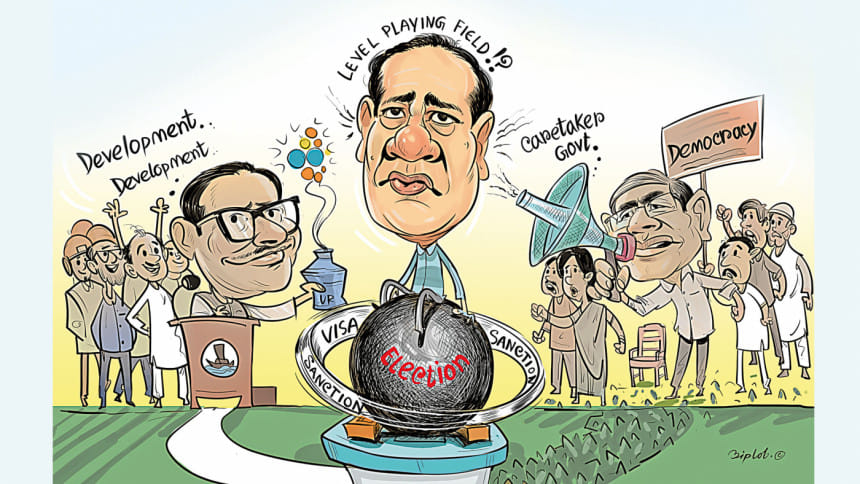

Truisms abound about elections. Some are discussed incessantly, while others are mentioned occasionally. The oft-discussed axiom is that "election is the foundation of democracy," but in the past decades, it has been followed by a caveat – elections alone do not mean democracy. In the 1970s, as democracy as an ideal and system of governance began to spread across the globe, elections were considered to be the key indicator and measure of democracy. Almost a decade later, it became evident to political scientists and policymakers that not all elections are democratic. The exaggerated importance of and unrealistic expectations about elections were challenged by the concept "fallacy of electoralism."

In subsequent decades, a growing body of literature showed that elections can also become an instrument of authoritarianism. A distinct form of hybrid regime called electoral authoritarianism, through which democratic and authoritarian traits blend, emerged. These regimes hold regular polls and create an illusion of a multiparty system; however, these elections remain unfree and are intended to provide a veneer of inclusivity. Besides, experiences have shown that elections are used by would-be-autocrats as a tool to rise to power. When in power, they use it as one of the weapons to legitimise their rule.

The second axiom about elections, not mentioned as much as the first, is that while voting is an election's key element, it is not only about casting the ballot on polls day. Election is a multi-step process that includes the pre-electoral period, the campaign, polling day, and the aftermath. Anomalies in any of these steps not only compromise the election's integrity and jeopardise its credibility, but also make the arrangement a hollowed exercise. According to the Open Election Data Initiative, "a credible election is one that is characterised by inclusiveness, transparency, accountability, and competitiveness." Established in 1998, ACE project, one of the largest online communities and repositories centring electoral knowledge, underscores the necessity of electoral integrity and reminds us that without such integrity, those who assume power "lack necessary legitimacy." Electoral integrity is crucial to understanding the characteristics of democracy, whether it be consolidated, emerging or regressing in a location.

These two aspects of election brought to the fore the role of institutions that manage polls. The management bodies, often described as electoral commissions, are principal institutions that shape the playing field and determine the modus operandi, not to mention the counting of votes. Consequently, a need for guidance and ethical principles arose. ACE laid out some principles in a document: it says that "an election management body (EMB) should be founded on principles of independence, non-partisanship, and professionalism. It should have clear procedures to make it accountable and have equally clear procedures for reviewing its effectiveness, both as a management organisation and as a service deliverer. It must be nonpolitical but capable of operating in a political environment." Additionally, ACE highlights ethical principles: "the integrity of election administration is crucial to ensure that the electoral process is considered to be legitimate. There is little point in holding elections, which are expensive operations, if the outcome is questionable because of either the inefficiency of the EMB or doubt about its impartiality."

With an election of great importance approaching and amid frequent debates surrounding Bangladesh's Election Commission (EC), the question of whether the current EC, headed by Kazi Habibul Awal, can deliver a free and fair election should be explored based on two sets of criteria – ensuring electoral integrity and adhering to guiding principles.

Concerning integrity, EC's behaviour implies that it considers the pre-election period as the time between the election schedule's announcement and polling day, usually 30 to 45 days. Even if we, for the moment, set aside the current political imbroglio on election-time government, it is easily discernible that the electoral process has already started. If nothing else, the EC could have listened to Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's speeches in various public gatherings where she has been asking people to vote for her party. These speeches are nothing short of a campaign. Few public service officials and police officers are already on board, violating the basic tenet of neutrality. Lest we forget, these are the officials who will be in charge during the polls.

Meanwhile, old cases against opposition leaders are being expedited and new cases are being filed every day, forcing the accused to spend almost every day in the hallways and docks of the courts, if not in jail. Persecuting opposition activists is not new, nor is it novel that an instrument called "ghost cases" is used. Unless the EC members lived in a different universe, they should have known that the judiciary was weaponised ahead of 2018 in an unprecedented manner. The deafening silence of the commission on the behaviour of public officials and the persecution of the opposition to tilt an already uneven field shows how the election's integrity is already compromised. The experiences of various by-elections over the past years do not paint a different picture. The EC's repeated assertion – that it has nothing to do with who participates, including the voters – betrays its responsibility to ensure inclusiveness.

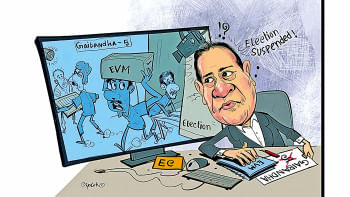

Regarding guiding principles, EC's questionable record is way too long but two subjects stand out: monitoring elections and registration of political parties.

Three episodes throw doubt on the EC's sincerity to ensure an election that is recognised by independent observers. The first was the red-carpet reception of an alliance claiming to have foreign observers. The so-called Election Monitoring Forum not only lacked the required credentials, but its purported head also has a chequered past; he was and is still actively engaged with a hazy group named Saarc Human Rights Foundation. The Forum provided a clean chit to the EC and government after the 2018 polls. Later, it was found that the alliance was, at best, a conglomeration of individuals with no experience of election monitoring, and, according to one member, didn't even know what they were up to. By any standard, this experience was supposed to make the commission cautious, but that did not happen.

The second episode is the decision to drastically reduce local election monitoring organisations this year. As opposed to 118 organisations registered during the 2018 polls, the EC decided to halve the number. Given the heightened attention to the upcoming election, international and domestic, it is hard to find the rationale behind this action.

The third episode involves the credentials of approved election monitors. According to the EC, 210 organisations had applied and 98 were shortlisted. The shortlisted organisations had been investigated by the EC "with assistance from two intelligence agencies" and 68 were approved. Media reports showed that the approved list has questionable organisations. For example, a leading newspaper that investigated around 32 organisations found that seven exist only on paper and 10 have politically affiliated individuals on their board. Some of them should not even be considered as organisations, as at best one or two individuals are employed in each of them, and they too do not have prior experience. Room for these "on-paper only" organisations were made by excluding many reputed and experienced local groups. How they passed the scrutiny of "intelligence agencies" remains a mystery. Although the EC has asked for a second round of applications for registration, it is not clear whether the dubious ones will be excised from the list. The first round of actions shows that for the EC, an appearance of having observers is enough to provide legitimacy, but these actions are contrary to international norms and guidelines.

Besides, while there is a long list of political parties willing to participate in the polls, many of which have significant presence nationally and in the grassroots, the EC decided to approve two new parties that independent investigations revealed lack key infrastructure even in the capital. Ministers and ruling coalition leaders joining a public event of one of the new parties provides a clue as to what prompted the commission to approve them. The word in the grapevine is that these parties have been propped up to make the next election "participatory," even if major opposition parties decide to boycott.

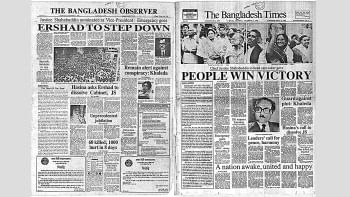

In judging the EC since its appointment in 2022, one must be cognizant of the fact that the commission members have been appointed under a law that has given the prime minister, the leader of the incumbent party, an opportunity to select the game's referee. In a similar vein, we will be fooling ourselves if we don't recognise the vital impediment to the EC's independence: a partisan government in power. Only the Election Commissions that served under a non-partisan government succeeded in delivering free and fair elections.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at Illinois State University, US, a non-resident senior fellow of the Atlantic Council and president of the American Institute of Bangladesh Studies (AIBS). His forthcoming book is titled Pathways to Autocratization: The Tumultuous Journey of Bangladeshi Politics (Routledge).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments