Economy shows signs of healing

When Salehuddin Ahmed was appointed finance adviser to Bangladesh's interim administration in August 2024, the country's economy was in a tailspin. Growth was slowing. Inflation was entrenched in double digits. Foreign exchange reserves were plummeting. The banking sector was in crisis. External dues, especially in the energy sector, were mounting, and revenue collection was far off track.

Twelve months on, the economic emergency has eased, but not been averted.

"When we took office, macroeconomic stability was in disarray," Ahmed said in a recent interview. "I would say the situation is reasonably satisfactory. When I took charge, the situation was precarious, but now things are working well. Reserves are increasing, remittances have risen, and export growth has been modest but steady. The foreign exchange market is stable, even after we liberalised it."

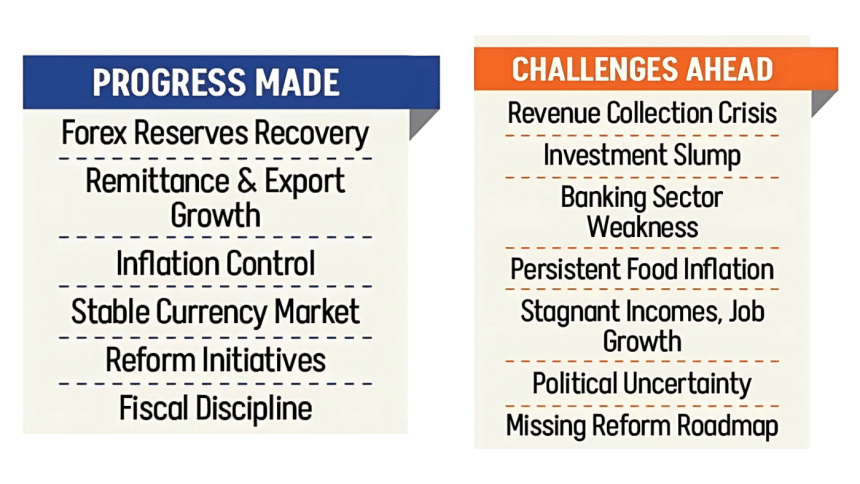

The comments reflect a sentiment shared by many: that their primary achievement has been stopping the slide, rather than engineering a turnaround. A closer look suggests that while the interim government has made gains on some fronts, especially inflation and reserves, it has left deeper reform challenges largely unaddressed.

Zahid Hussain, former lead economist at the World Bank's Dhaka office, said the government's approach has been more conventional than transformational. "After the interim government took office, it implemented the previous government's budget and, at the same time, presented a new one," he observed. "After such a major change, we haven't seen the mark of any change. I am not saying whether that is good or bad. That is what happened. No innovative change was seen in the new context."

The economic situation inherited by the interim government was anything but normal. According to data from the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics, point-to-point inflation reached 12 percent in July 2024. It had stayed in double digits for six out of seven previous months and had hovered above 9 percent for nearly three years, the longest such stretch in decades.

"Inflation didn't come down here because of flawed monetary and fiscal policy," said Mustafizur Rahman, distinguished fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD). "The previous administration relied too heavily on administrative price control and liquidity pumping. The interim government had to shift course immediately."

That shift came in the form of tight monetary policy. The Bangladesh Bank, without waiting for IMF directives, raised the policy rate multiple times and allowed the exchange rate to adjust more flexibly. Fiscal policy was also redirected: development spending was curtailed, and growth targets were adjusted downward.

"Unlike the past, we didn't try to suppress the exchange rate artificially," Ahmed said. "We stopped intervening excessively in the market. That has helped stabilise remittances."

Indeed, remittance inflows rose 26.46 percent in FY25, reversing years of stagnation. Exports also rebounded, increasing 8.58 percent, after contracting nearly 6 percent in FY24. Combined, they contributed to a recovery in gross reserves, which stood at $32 billion by June 2025 under the central bank's accounting, and $27 billion under the IMF's BPM6 standard.

The government's monetary tightening had an effect: point-to-point inflation finally fell below 9 percent in June 2025, the first time in nearly three years. The finance adviser believes this has provided tangible relief. "Overall, the pressure on the cost of living has been significantly alleviated," Ahmed said. "The price of rice is stable, although there are some fluctuations in the price of fine rice."

But the 12-month moving average still remains above 10 percent, and food inflation continues to strain low-income households. "We've seen progress, yes," said Mustafizur Rahman. "But the pace is slow, and people are still hurting. Income growth hasn't picked up, and employment generation remains stagnant."

REVENUE COLLECTION: THE ACHILLES' HEEL

If macroeconomic stabilisation has been the interim government's main success, revenue collection is its most glaring failure.

In FY25, revenue collected by the National Board of Revenue (NBR) grew just 2.23 percent, compared to 15 percent the previous year. The government fell short of its revenue target by over Tk 100,000 crore, with actual collection totalling Tk 371,000 crore. Bangladesh's tax-to-GDP ratio remains among the world's lowest.

The finance adviser disputes the severity of the problem. "It's not that there has been a major collapse in revenue collection," Ahmed argued. "There is growth."

A key reform initiative has been the separation of the tax and customs departments, long recommended by development partners. The move triggered internal protests from revenue officials, but the finance adviser has not backed down. Even critics see this as a positive development.

"The separation of the NBR is a bold step," acknowledged Zahid Hussain. "By not backing down from it despite the agitation, it has been possible to send a strong message. There is a lesson to be learned from this: resistance will come with major reforms, and how to manage it better." The reform is expected to be completed by December 2025.

Despite the poor revenue performance, the government exercised unusual fiscal restraint. In FY25, the administration did not borrow from the Bangladesh Bank, and bank borrowing totalled Tk 72,372 crore, well below the revised target of Tk 99,000 crore.

Perhaps the most worrying signal is from the real economy, where investment remains depressed.

In June 2025, private sector credit growth was just 6.4 percent, far below the 12-14 percent typical of a growing economy. LC openings for capital machinery imports dropped by 25 percent, while settlements for intermediate goods and raw materials also declined. Public investment didn't compensate either. ADP implementation stood at just 69 percent, the lowest since Bangladesh's independence and a major drag on overall GDP growth.

Ahmed attributes the slump to political jitters. "In the world of business, there is still some uncertainty or lack of confidence. This is mainly because there will be an election in the country, and what may or may not happen. It is natural for business people to be a little concerned about all this. However, confidence is now returning compared to before."

He also pointed to structural issues, adding, "Secondly, some banks have liquidity problems. Then again, some banks are unable to provide loans."

This acknowledgment points to another critical, unfinished agenda: the banking sector. "The banking sector had hit rock bottom," Ahmed said. "From there, it has returned to a reasonably normal state. There were some bad banks, not all of which have become good. Bangladesh Bank is looking into it seriously. The BB will restructure them."

For analysts like Hussain, the lack of a clear, time-bound plan for such reforms is the budget's biggest weakness. "Another expectation from the new budget was that there would be a clear and specific timeline and roadmap for reform," he said. "For example, if there had been a roadmap stating how many banks the interim government would merge during its tenure, which reforms would be carried out in the revenue sector, what reforms would be done in the fuel, power, and port sectors, what reforms would be made in the next two years, then it could have been measured later."

This critique cuts to the heart of the interim government's dilemma. After one year, Ahmed's performance can be summarised as macroeconomic containment without a structural breakthrough. Inflation has eased, reserves have recovered, and external dues have been settled. But the revenue crisis, weak investment, and unfinished reforms present growing threats.

Defending his government's pace, Ahmed pushed back against what he sees as textbook criticism. "Economists generally criticise from within a framework. But the reality is different. Making any policy is not that easy a task," he said. "The budget is like a balloon. If you press one side, the other side will bulge."

As Bangladesh prepares for election in February, whether the opportunity to deliver a deeper transformation can be materialised remains to be seen. The interim administration has successfully pulled the economy back from the brink of a full-blown crisis. Yet, this stability is fragile.

With the political clock ticking down, the window for making difficult, and potentially unpopular, structural reforms is perhaps closing. The government's focus may inevitably shift towards ensuring a smooth electoral process, leaving the tough economic decisions for the next elected administration. The coming months will therefore be a critical test.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments