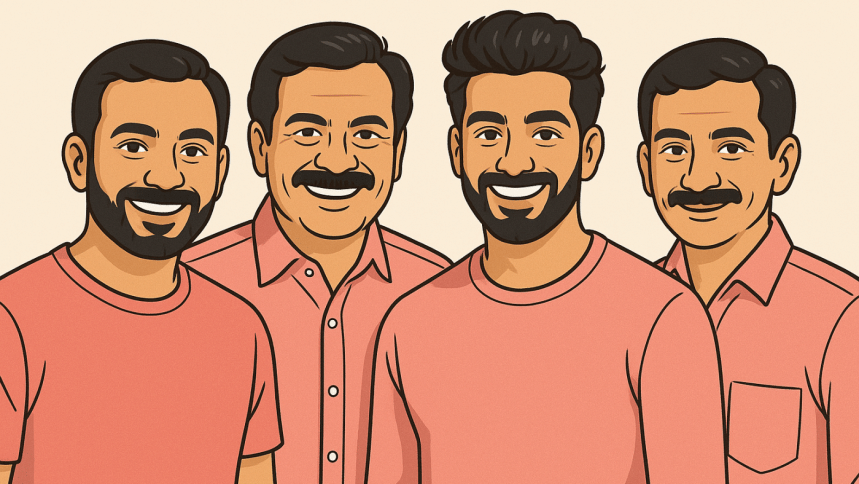

Finding the men in pink

I follow a food vlogger, and in one of her posts, which was not food-related, she mentioned something in line with men wearing pink. It hit a chord in me, although I was not thinking about fashion because at that time my head was full of thoughts like "men in pink and women in blue".

The colours for me spoke about breaking prescribed gender roles. I was toying with the stereotypes about masculinity and femininity. Things like what a man should do and how a woman should behave, how their roles are all dictated, etc.

The stereotypes of men as the sole breadwinners and protectors, and women as only caregivers and homemakers, were not going well with my emotional resonance. There is nothing wrong with men being supportive of their female counterparts. If they respect each other's position in the social milieu of how they live, think, and act, the question of dominance does not arise.

But it is undeniable that traditional power structures keep women as subordinates, and men want it to stay that way.

We detest women

The blatant public displeasure for women who are unafraid to challenge societal norms, the outcry and resistance against any effort to promote women's rights, is downright unacceptable. The fiasco regarding the proposed recommendations made by the Women's Affairs Reform Commission in Bangladesh, followed by the almost unanimous reaction or consensus of both men and women in certain strata of our society towards this resistance, has been quite a shock for me.

Agreeing with me, Srijon Shaikat, a young man studying at the Independent University, says, "Beating a woman effigy like a piñata is not a protest, it is equivalent to symbolic violence. As a 23-year-old student, I refuse to accept a narrative where women are told to stay indoors while men police public space. This is not faith; it is fear of female agency. The world is watching, and moments like this only push us further into the shadows of extremism. Bangladesh deserves better."

"It is interesting that many of these people appear to be reacting without even fully understanding or engaging with the content of the commission's recommendations. Their opposition seems rooted more in fear and misinformation than in informed critique," thinks Monjun Nahar, a gender expert and acting head of Partnership and Fund Raising at Marie Stopes Bangladesh.

A fellow journalist also has similar views: "Any society needs to have the liberty to choose and decide without coercion. Videos of demeaning women will incite people with little knowledge of the topic to harm women. This tutors and instigates men to be ruthlessly aggressive towards women. This cannot be the teachings of moral righteousness. People will treat these incidents as free passes to look down on women and cause harm".

This expression of disgust by them made me happy to know that there are men in pink or men who support women's rights.

Nahar thinks that these groups who have made such vitriolic statements against women often interpret gender equality initiatives as a direct threat to their control over societal norms, especially those that define and restrict women's roles. Their response reflects a deeper anxiety about losing authority and influence over public discourse and private life, particularly regarding women's autonomy, rights, and access to resources and decision-making power.

Inbuilt misogyny

The beating of a woman's effigy simply displayed a perverted hatred towards women, and strangely, women too are hating on women.

Our societal culture declares progressive, smart, independent, successful, and bold women and young girls as "bad".

"Stereotyping of women as 'good girl' and 'bad girl' is planted in both our sons' and daughters' minds from a very young age, initially by their mothers and then by the society at large," explains Sirajul Hossain, a social researcher and managing director at Cybernetic Systems Ltd.

It stems from a very critical and internalised misogyny where the mother has subconsciously adopted and applied sexist beliefs and stereotypes learned from society onto themselves, other women, and her children.

"Women who fall victims to internalised misogyny are now minimising the value of women, mistrusting women, and believing gender bias in favour of their male child. She portrays a picture of good and bad girls from her sense of prejudice and influences her son to find a good wife who would protect the family. And the men, on the other hand, have taken it as their moral responsibility to punish the bad girls," Hossain continues.

Looking for moderate perceptions

Monjun Nahar believes that the first impact of such violence is on women and girls, who feel increasingly helpless and vulnerable. This pervasive sense of insecurity has severely restricted their mobility, especially after sunset, she adds, as they are afraid to leave their homes. The culture of fear is becoming deeply embedded, creating significant constraints on their ability to lead normal, dignified lives.

"In such an environment, women's access to education, employment, and health services is also being compromised. Their participation in public life will shrink, and their voices will be silenced. This atmosphere not only violates basic human rights but also reinforces harmful gender norms and deepens social inequalities."

She also points out that the commission has proposed several critical aspects of women's development regarding property rights, access to healthcare, and participation in economic activities, which are essential for women's empowerment.

Nahar suggested a principled stand, confirming our commitment to non-discrimination and not capitulating to regressive pressures, especially when they contradict the values of equality and justice.

Bangladesh is a signatory to international human rights conventions, including the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). Dismantling any commission dedicated to women's rights would violate these obligations, says Nahar. Not to mention that it will tarnish the country's international image as a development success story with notable gains in gender equality.

I feel my city Dhaka's society at large has always been liberal, accommodating, and courteous; outright hatred is not something Dhaka people carry with them. Generally, the core of Dhaka is moderate groups of people practising their own beliefs. Moderate perceptions, I believe, are denouncing extremist violence, be it political, religious, or social.

I strongly believe that most of the residents of my city have risen above rigid patriarchal norms. I need to find Dhaka's men in pink and women in blue. I know they are out there.

Raffat Binte Rashid is editor of My Dhaka at The Daily Star.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments