The Mughal fort that became a British prison

Walk down the lanes of Old Dhaka today and it is hard to imagine that the city once revolved around a single building -- Dhaka Fort. Back in 1610, when Islam Khan, the Mughal subahdar of Bengal, shifted his capital here, the fort was the nerve centre of Mughal power.

According to historian Dr Abdul Karim, it stood opposite today's Chawk Bazar, on the site where Dhaka Central Jail would later rise.

The fort was no silent spectator. It housed Mughal subahdars, the royal mint, and most ominously, a prison. Unlike the British jail that came later, this one held political detainees. Local zamindars and rebel leaders often ended up there, awaiting orders or verdicts.

The fort's fortunes shifted over the years. Renovated in 1690 by Subahdar Ibrahim Khan the second, it gradually lost importance as new palaces and administrative quarters were built across Dhaka. By 1765, after the East India Company assumed control of Bengal, the fort was in their hands. Two decades later, in 1788, its prison wing expanded, and by the turn of the 19th century it had assumed a new identity -- Dhaka Jail.

Dhaka in the early 1800s was a shadow of its Mughal glory. Once-bustling Ramna had turned into a jungle so dense it was thought to endanger public health. Charles Doss, then magistrate of Dhaka, intervened. With little government funding available, he turned to the 'free labour force' at Dhaka Jail. In 1825, prisoners were put to work clearing Ramna. After three months of hard labour, they had cleared an oval-shaped section.

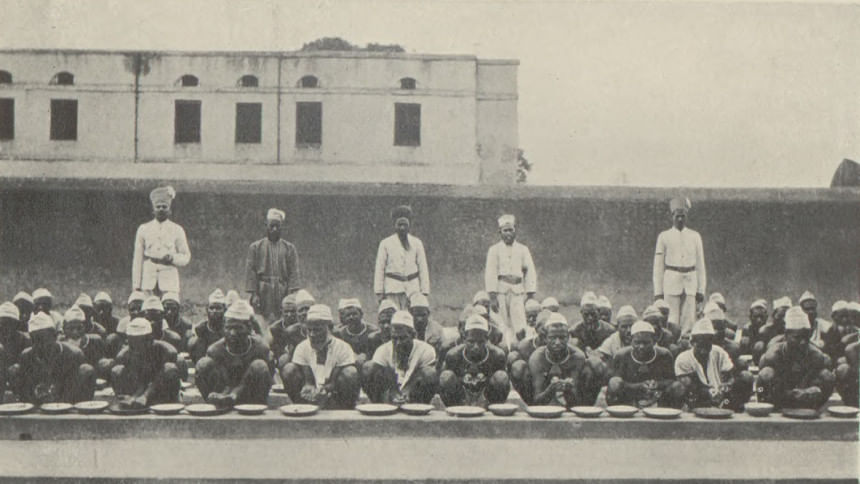

By then, Dhaka Jail had grown into a formidable institution. Reports from 1839 describe 10 wards, each with its own courtyard, and a massive wall enclosing the compound. The jail held around 800 criminals and about 30 civil prisoners, convicted of crimes ranging from murder and robbery to cattle theft, forgery, arson, rape, and adultery. Prisoners frequently fell ill, prompting the construction of a hospital inside. Built in the 1830s, it was a simple structure -- a long hall with arched passages, verandas, and rooms for isolating the sick.

By the mid-19th century, Dhaka Jail was one of East Bengal's most important prisons. Inmates were put to work producing chairs, tablecloths, curtain fabrics, mustard oil, and even lime paint. Some of these items were sold in the market. Jailers, mostly Europeans, earned a modest 100 rupees a month, but supplemented their income by taking a 5 percent cut from sales. Some even set up private businesses inside the jail.

Arthur Lloyd Clay, joint collector of Dhaka in the 1860s, noted that prisoners often left the jail looking healthier than when they arrived. Adequate food and care made the difference, though treatment was not equal. European inmates received prime mutton and could complain if the quality fell short, while native prisoners had no such privilege.

By the 1860s, Dhaka Jail had become the main facility for "difficult" prisoners across East Bengal. Convicts from Sylhet, Tripura, and Faridpur were sent there, and by 1879 the prison was officially declared the Central Jail for Dhaka and Chattogram divisions. With its new status came new responsibilities.

A superintendent replaced the magistrate as head, and expenses soared. By 1893, the annual cost of running the jail -- food, clothing, hospitals, and staff -- totalled Tk 51,328, a significant sum for the time.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments