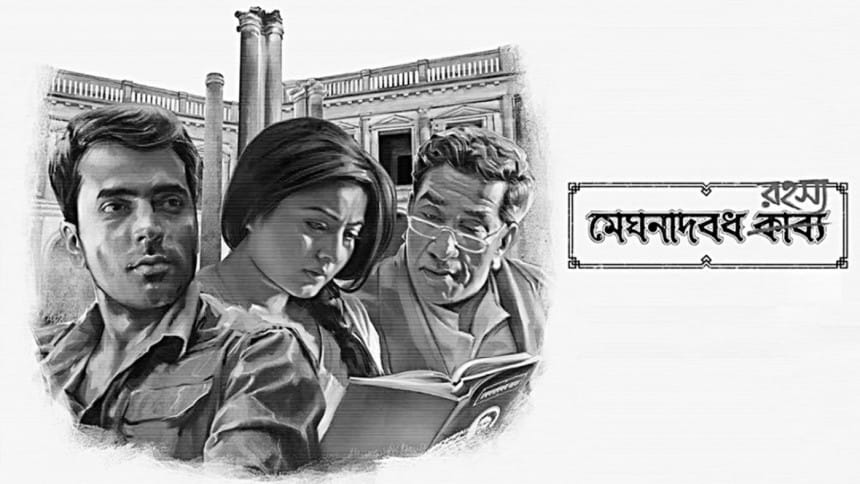

Spoilers Alert: Meghnadhbadh Rahasya Revealed

Anik Dutta's 2017 movie Meghnadhbadh Rohoshya is a clever evocation of naxalgia. Fifty years after the Naxalbari movement, the movie revisits the revolutionary moments when some young talented students took up arms against the landed and urban propertied classes. Imbued with Marxist-Leninist-Maoist ideologies, these activists dreamt of a classless society, only to be brutally shattered by the ruthless State agencies. Naxalbari in Siliguri under Darjeeling district was the ground zero of a long drawn out movement led by Charu Majumdar. Many stories have been written and many movies have been made in both West Bengal and South India depicting the nuanced reality of this left struggle.

What began in 1967 as a movement of indigenous people's rights to cultivate their land became a regional site of ideological conflicts against the backdrop of the Sino-Soviet rift. The Maoist adaptation of Marx inspired a new generation of leftist activists to put theory into praxis. The events dominated the public imagination through the works of writers who saw the best having all passionate intensity, and the worst lacking convictions (apologies to WB Yeats). Mahasweta Devi's "Hajar Churashir Ma" is a classic example where a young revolutionary Broti (symbolically resonating 'promises') is shot dead by police and his corpse is tagged as 1084. Broti's mother Sujata laments how her son's identity is effaced. Samares Majumdar's Animesh series, especially Kalbela, brings out the romance surrounding the Naxalites. Anik Dutta's film dares to re-engage with the historicity by embracing multiple perspectives and agencies.

The filmmaker's deconstructive mode is evident in the title where he uses 'under erasure' to cross out 'kabya' and insert 'rohoshya.' Michael Madhusudan Dutt's epic, Meghnadhbadh Kabya, is famous for its glorification of Meghnad, the son of the villain Ravana. Dutt is inspired by Milton's Paradise Lost where Satan is portrayed sympathetically. The Indian epic points out betrayal as the main theme that leads Rama's brother Lakshman to kill an unarmed Meghnad through the help of Bibhishan. Anik Dutta makes the mythical narrative available in a popular discourse by presenting the epic as a "Whodunnit? howdunnit? whydunnit?" mystery subgenre.

Central to the movie is a former Naxalite, an award winning sci-fi writer, Asimava Bose who now resides in the UK. The frame narrative begins with a story that (we later learn) Asimava is currently writing involving the anti-British Swadeshi Movement in 1936. The frame shifts to Oxford in 2016, where someone receives a mail containing a copy of Meghnadh Badh Kabya. The next frame shifts to Gautam Halder's stage performance, Meghnadh Badh. The dance drama transports the audience to a mythic time with carefully chosen passages to remind them that they are about to enter a 'Madhu-Chakra': the Romantic notion of a poet as a bee that gathers honey from different sources with a possible pun on the Circle of Madhsudan's oeuvre. The plot then moves to the launch of an award-winning book in Kolkata in December 2016.

During the session, we learn that the leftist leftie author Asimava Bose is now a right-handed writer. His physical orientation is suggestive of his political shift. The author of, The Big Bong Theory, downplays his involvement with the Naxalite movement by saying, "at that time everyone got a little involved." As the plot unfolds, we get introduced to Asimava's second wife Indrani—an actress and a social worker. She is assisted by someone called Janaki. Indrani has a daughter from her previous marriage- Buli. Indrani has a film director friend Kunal. Asimava's first wife is paralysed, and together they had a musician son called Hrik. It is Hrik who has introduced Asimava to his translator Elena. Asimava's Kolkata house is looked after by a distant relative called Bulu, whom Asimava calls a "bloody parasite." Asimava's westernized friend Nikhilesh uses his painter/curator facade to camouflage his involvement in art-smuggling. And there is a little-magazine editor called Badal Biswas who leads a secret life in underground politics.

The movie attains its dialectics through some deliberate pairings. There are two of everything. Asimava has two wives: His first wife Hrik's mom is old, paralyzed and wheel chair bound, while his second wife has earned her fame through her film, Shiri (suggesting moving on for moving up). There are two children: one biological and the other step. There are two 'pimps' from two different classes: Nikhilesh is an art smuggler and Bulu rents out the house to dodgy customers. The two classes are distinguished by their locations: The upper class drinks in the living room whereas Bulu and his male 'lover' steal whiskey to drink in the kitchen. There are two secret activists: Janaki and Badal. There are good cops and bad cops. The metanarrative presents a story within a story; one that shows Asimava writing a confession in a Bankim like style using shadhu bhasha in his effort to defamiliarise his narrative. The spatial setting moves between England where independence is seen as a distant dream and India where freedom is still illusory in an independent country. There are even two 'Marx' in the movie. Asimava's house has a Marxism poster that features the American comedian Groucho Marx with a cigar. The kitsch makes no secret of Asimava's attitude towards his ideology that he once championed. The wounds of Old Marxism are scratched when he is unsettled by the news of an attack on a Police van. His old Comrade Sirajul, in contrast, has the poster of Karl Marx in his room. Sirajul and Asimava have opted for different routes. According to Sirajul, as revealed to Indrani and Kunal, Asimava was nothing more than a 'political hobbyist' who had a Romantic notion of the Naxalite Movement.

The mystery deepens when Asimava starts receiving coded threats with reference to Michael Madhusudan's epic, forcing him to confront his past when he ratted out one of his comrades to earn a safe passage to England. The guilty feeling torments him. Asimava tries to tell his side of the story in fiction with a therapeutic purpose. Asimava, as an expatriate writer living in a foreign land, knows that he is not free. His friends who are living in an independent country are not free either. "We who had united to break the shackles are now living in our own solitudes."

Asimava is an escapist. He runs away for the second time in a self-imposed disappearance that harps the main mystery motif. And the person responsible for sending Asimava into his guilt trip is his friend's daughter, Janaki, who covertly works with Indrani. The answer to the riddle is a pun on the nomenclature. 'Jano Ki'? Do you know? It is the question that haunts the failed revolutionary moment. For Janaki, it's a personal quest for understanding why her father, and by extension his convictions, were betrayed.

Asimava tells Janaki that he had given away information about her father only to protect himself from third degree torture that had crippled his left arm. He was promised that the police would not harm Indrajit. By that time, Asimava too had become disillusioned by the prospect of the Marxist-Maoist movement. Because the movement lacked any central coordination, the movement unleashed unprecedented anarchy losing popular sympathy. Yet the Naxalite movement still today occupies an uncanny zone in the Bengali psyche with its promised output of a land without any exploitation.

However, Naxalite is a movement that separated families, ripped societies open from inside. In Satyajit Roy's "The Adversary," for instance, we have seen one brother being pitted against the other. The older brother has sympathy for his younger Naxalite brother. But he realizes that the cause has become bigger than the individual; the younger brother is so insignificant that he becomes a mere agency of carrying out somebody else's instructions. He loses his identity and agency in the process.

Anik Dutta's movie is alive to the nostalgia about the Naxalite movement. It not only adds some human faces to history but also explains some serious ideological issues in popular terms. One may wonder why Janaki is investing so much of her time and energy in executing revenge on the person who betrayed her father than on the system responsible for the killing of her father! Does it mean Janaki has accepted the historical fact that the system cannot be changed? The turncoat handicapped Asimava is the target as he epitomizes the conscience that has got used to being compromised and complacent. He is the symbol of a failed political dream. His retreat therefore can be a treat for the new generation of activists who can ask "jano ki" – do you know your story, your history?

Shamsad Mortuza is the Pro VC, and the Head of the Department of English and Humanities at University of Liberal Arts Bangladesh.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments