A Persona non grata: 'Subodh' in the Streets of Dhaka

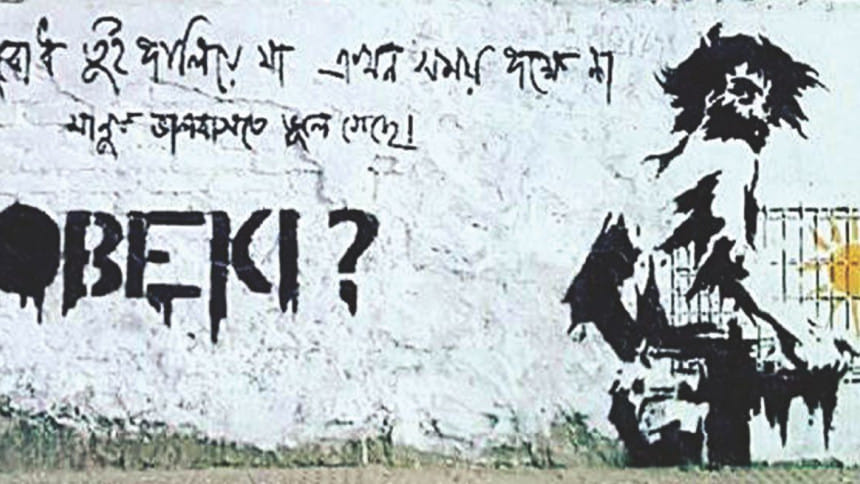

Two years ago, on a cool afternoon in November, driving towards the cantonment gate at the intersection past Radisson on the Dhaka-Mymensingh highway, a sign caught my attention. I was back in town and busy looking about at people, automobiles and the passing vista of concrete and steel, when I almost missed the plaintive-looking block letters in English that read (impetuously asked!) 'HOBEKI?' I churned around the alphabets in my mouth; cogitated on the sound it made and spelt it several times forwards and backwards so as not to miss the gravity of its manifestation. The ensuing effect, needless to say, was delightful. I quietly rejoiced at the prospect of an ingenious local graffiti artist but longed to know nonetheless who decided to put up the sign on this very spot, to say nothing of what it meant.

I interpret the HOBEKI graffiti in two ways. The first as a quasi-propitious question: 'will/might/can it happen?' The other meaning of the phrase, that 'nothing will/can happen' or that 'nothing happens' is of course the bleaker version of the former, indicative of a futility of purpose. 'HOBEKI,' as with most graffiti writings, cleverly plays on the dynamic dialectic of opposing meanings of the phrase as it fashions a semiotic pun on the precariousness of words and their meanings that shift with the alteration of the context in which words and signs co-exist.

Graffiti pertains to visual signs (from unintelligible scrawls to elegantly printed slogans) scratched onto a wall or public surface. Street-art, on the other hand, is a sub-genre of graffiti writing. Most graffiti writing appertains to a secret or internal language of sorts, often intelligible to graffiti circles. Street art and graffiti first sprang up as a sporadic reaction to the rising urban renewal schemes and suburban development projects by real-estate investors in the Bronx communities of New York in the late 1960s. While these housing schemes generated new money for entrepreneurs, the local communities who were arbitrarily displaced and relocated suffered massively. In the subsequent eras of economic decline, street art and graffiti were born out of this miserable atmosphere of brick, metal and mortar. Most graffiti artists in New York hailed from multicultural backgrounds that in turn reflected the cultural diversity of this community. With no financial assistance, and with little or no art-school training, the first group of graffiti artists used mainstream pop culture and comic books to give expression to their vision of postmodernist graphic art.

Over the past few decades, street art has gradually spawned a global protest movement of sorts. Artists and illustrators from across the world, ingeniously re-invent through visual metaphors an urbanized world where the gulf between the rich and the poor is widening at an alarming rate resulting in large-scale displacement, migration and dislocation of people. The public reception of street art remains divided to this day between its admirers who appreciate its artistic élan, and critics for whom street art is concomitant to gang culture that vandalize public spaces and private properties.

The past fifty years have witnessed a marked rise in the production of street art and the interest therein with the expansion of new forms of this art form proliferating the city centres, public domains and communal, urban spaces on a global scale. Street artists such as Banksy have been lauded as an activist and campaigner of human rights in the refugee crisis in Europe and the on-going Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Banksy's poignant pop-up murals in the refugee camps in and around the Calais Jungle area in France pose important questions on global citizenship and ethnic displacement and the West's role in perpetrating this displacement. Similarly, his daring murals in the Israeli occupied area of the West Bank offer a graphic critique of the unlawful occupation of Palestinian land.

Wall art comes to Dhaka

The recent spates of street art accompanying the HOBEKI graffiti that have sprung up in the urban word-scape of Dhaka and have been of late, socially ambivalent and politically ambiguous. The 'Subodh series' comprises of a set of images created using stencil and spray paint. It depicts the figure of a gaunt young man in tattered jeans, sprinting away with a cage in his hand bearing a brightly lit sun. The Bengali captions accompanying the graphic narratives address the young man called 'Subodh' with urgent instructions to flee because neither 'time' (shomoy) nor 'luck' (kopal) are purportedly on his side.

The series showcases an on-going existential narrative, a short chronicle of daily maladies taken from the pages of a life lived rough: we see a despondent Subodh sitting on his haunches, hand on his head in a gesture of dejection; Subodh absorbed in a conversation with a little girl; Subodh picking up the cage and breaking into a run; and Subodh behind bars, his tear-strewn eyes staring hauntingly at ours. While the illustrations may appear simple, the messages behind these are anything but simplistic. For Subodh the message is a plaintive imperative to run away because 'people have forgotten to love,' for the spectator, the series perhaps intimates that we have to learn how to look and to look anew at the intricacies of the urban fabric of the city.

Wall art implores engagement with the urban spaces of the city: it demands to be looked at. One becomes more aware of the physical space of the city by engaging with street art and graffiti. The mystery surrounding who produces these visual-verbal signs is as intriguing a question as who is watching or reading it. I argue that 'Subodh' exposes the untold stories of hardships that make and break a city. 'Subodh' encourages the spectator to look at the urban landscape of Dhaka in a new light away from the visions of sustainable development projects and housing projects to the drab realities of neglect and alienation.

Dhaka is one of the most over-populated megacities in the world. A recent report by UNICEF shows that about 41 million people live in the urban areas of Bangladesh. While the urban growth of Dhaka metropolis is quite remarkable, it has also given rise to housing problems. The huge population growth and the demand of a vast number of people to want to relocate to the urban centres have led to haphazard and unplanned urbanization. While the city's commercial and economic activities attract a large urban labour force, the city is not structurally equipped to accommodate this vast sea of people. This has lead to a marked rise in congestion and the urban poor who live in conflicted spaces often producing slum cities within megacities.

While much critical scholarship on Dhaka addresses the socio-economic woes of its urban poverty, it is perhaps the first time that street art has made a foray into this debate. Street art and graffiti writings are never solely aesthetic; they reflect the socio-cultural and political climate of the times. The advent of the 'Subodh series' in the streets of Dhaka is timely in light of the large-scale global and local crises of refugee dislocation and migration that we have witnessed in the past few years. 'Subodh' is an ideological expression of protest and socio-political commentary that reflects strains of the current crises of dislocation, both on a global and on a more localized, urban levels.

The series is especially notable for its singular depiction of the human cost of displacement in urban Dhaka, a city of staggering demographic inequalities and infrastructural irregularities. The images offer a parallel vision and voice of the city that we have perhaps inured ourselves to forget. Away from the political and commercial graffiti clamouring for space in the public walls of the metropolis, 'Subodh' offers fresh insight into the simple and hardworking 'everyman' figure who has perchance travelled many miles to arrive in Dhaka.

Moreover, 'Subodh' touches upon the notion that we are tirelessly moving between cities, states and countries, legally as citizens and illegally as refugees and travellers in exile in a world that is interlaced by contested borderlines and imaginary boundaries. 'Subodh', therefore, can be read as a story of the plight and dire predicament of urban refugees and of marginalized people relentlessly pursuing elusive dreams of material wealth and acceptance and being pursued by societal forces. While the number of refugees in general continues to rise, more and more urban refugees are relocating to the big cities and urban locations.

Appearing predominantly in the industrial zones of the city, 'Subodh' invests new meaning to the areas it occupies in the urban landscape of Dhaka as locations of unprecedented capitalist opportunities that are unevenly delineated for the urban poor who exist on the margins of society as nameless, faceless and voiceless entities haphazardly categorized as day-labourers, migrants and nondescript outsiders. By reflecting on the unspoken tensions and incongruities that manifest the urban fabric of Dhaka, 'Subodh' offers critical insight into the forgotten stories that in many ways continue to shape and define the Dhaka we know today.

Mahruba Mowtushi is Assistant Professor, Department of English & Humanities, ULAB. Her research and writing interests cut across South Asian and African literature and cultural history.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments