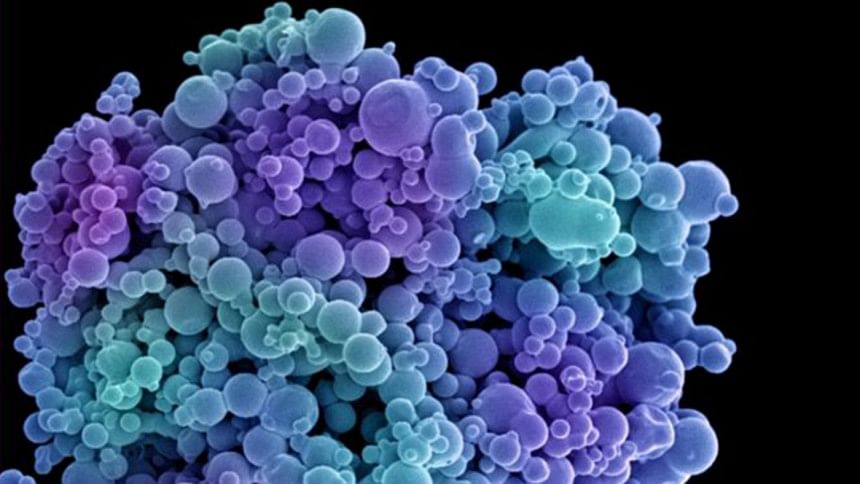

Breast cancer: Scientists hail 'very significant' genetic find

Scientists say they now have a near-perfect picture of the genetic events that cause breast cancer.

The study, published in Nature, has been described as a hugely significant moment that could help unlock new ways of treating and preventing the disease.

The largest study of its kind unpicked practically all the errors that cause healthy breast tissue to go rogue.

Cancer Research UK said the findings were an important stepping-stone to new drugs.

To understand the causes of cancer, scientists have to understand what goes wrong in our DNA that makes healthy tissue turn cancerous.

The international team looked at all 3 billion letters of people's genetic code - their entire blueprint of life - in 560 breast cancers.

They uncovered 93 sets of instructions, or genes, that if mutated, can cause tumours. Some have been discovered before, but scientists expect this to be the definitive list, barring a few rare mutations.

'Mutational signatures'

Prof Sir Mike Stratton, the director of the Sanger Institute in Cambridge which led the study, told the BBC News website: "In the latter part of the last century we were able to identify the first individual genes that became mutated.

"Now with our ability to sequence the whole genome of very large numbers of cancers we're moving to essentially a, more-or-less, comprehensive or complete list of those mutated cancer genes so it is a very significant moment for cancer research."

And crucially, each of those mutations is also a potential weakness that can be used to develop drugs.

"This is no longer speculation or hand-waving," said Prof Stratton. Targeted drugs such as Herceptin are already being used by patients with specific mutations.

Prof Stratton expects new drugs will still take decades to reach patients and warns: "Cancers are devious beasts and they work out ways of developing resistance to new therapeutics so overall I'm optimistic, but it's a tempered optimism."

There is also bad news in the data - 60% of the mutations driving cancer are found in just 10 genes.

At the other end of the spectrum, there are mutations so rare they are in just a tiny fraction of cancers meaning it is unlikely there will be any financial incentive to develop therapies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments