Like an undying phoenix, the spirit of Nazrul lives on

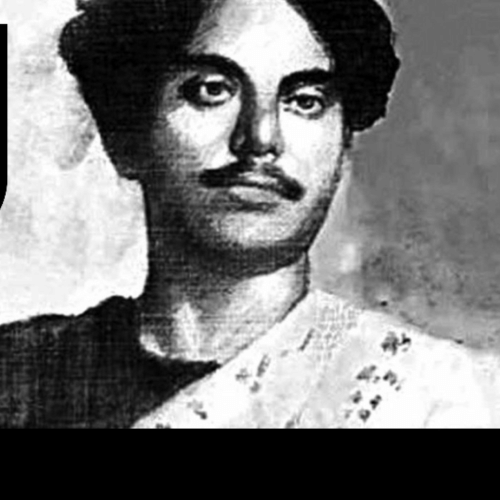

Is it coincidence, or inevitability, that Kazi Nazrul Islam's verses echo whenever Bengal rises in defiance? Each uprising, each cry for freedom, seems to find its mirror in the words of this fiery young man who, at just twenty-two and fresh from the mud of the First World War, sat with a wooden pencil in a modest Kolkata room and gave birth to "Bidrohi" (The Rebel).

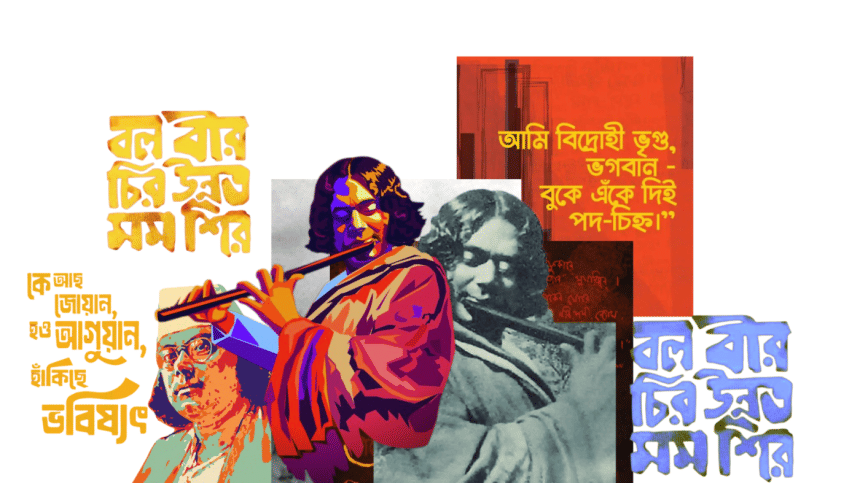

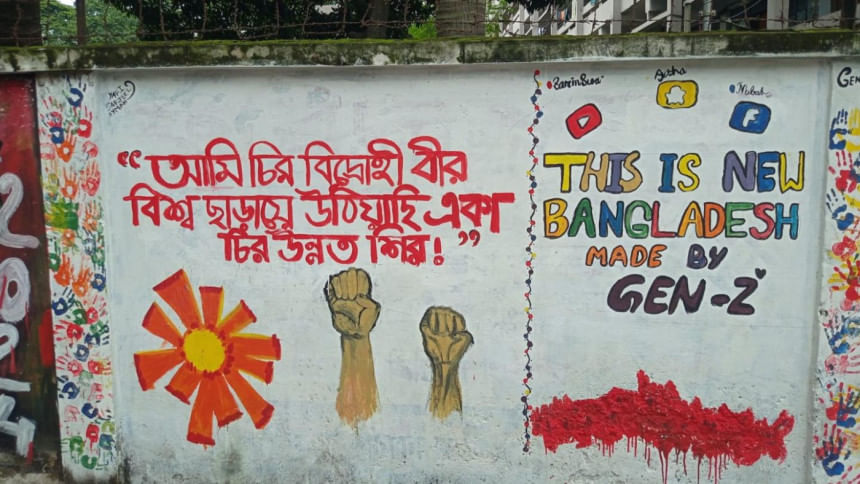

That night in December 1921, while his comrade Muzaffar Ahmed slept, Nazrul scribbled furiously. By the morning, the air was charged with something new. "Bolo Bir, Chiro Unnoto Momo Sheer…" ("I am the Rebel Eternal, / I raise my head beyond this world, / High, ever erect and alone!") he declared. It was not merely the birth of a poem but of a cultural rupture. Critics would later see in "Bidrohi" a break from the 'Rabindric' serenity that had long defined Bengal's literary landscape—a new current of words forged in fire, laced with the clang of rebellion.

In each of our fate-defining uprisings, resistance, and even a brutal war, revolutionaries kept their spirit high and unbroken against death.

Nazrul's verses struck at the very marrow of oppression. "Bolo Bir, Chiro Unnoto Momo Sheer" ("Proclaim, Hero, my head is ever held high"), "Ami Aponare Chara Kori Na Kahare Kurnish" ("I bow to none but myself"), and "Ami Mani Na Kono Ain, Ami Oniyom Usshringkhol" ("I obey no law, I am unruly, disorderly")—these were more than poetic flourishes; they were manifestos, thunderbolts hurled at both colonial authority and social convention.

But the rebel's pen did not stop at empire. Nazrul turned his fire against the internal chains that shackled society—caste hierarchies, economic disparity, and the poison of communal division. "I do not bend to anyone," he roared, as if to remind Bengal that true freedom meant dismantling every hierarchy, not just the colonial one. In this way, his rebellion was at once national and universal.

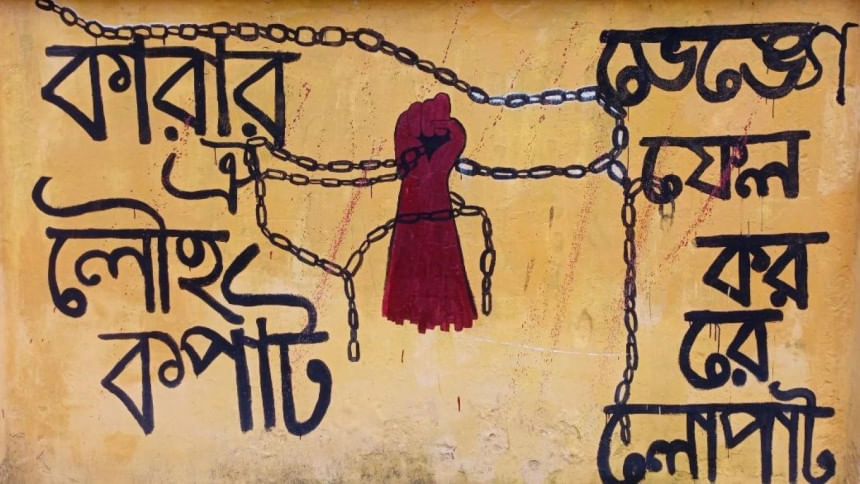

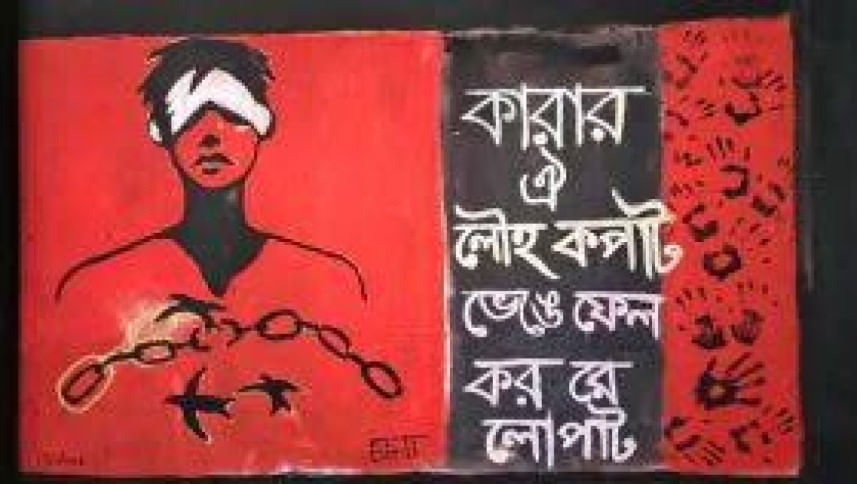

His "Bhangar Gaan" ("Song of Destruction"), first sung in 1921 after his return from Comilla, still reverberates like a clarion call:

"Ore o torun Ishan, Baja tor proloy-bishan!

Lathi mar, bhang re tala,

Joto shob bondi-shalay—

Agun jwala, agun jwala, phel upadi!*"

("O young wind, rise and blow your doomsday horn! Break the locks, smash the chains, set the prison houses aflame!")

The British Raj understood the danger of such words. "Bhangar Gaan" was banned by 1924, and soon after, his incendiary "Prolay Shikha" met the same fate. His newspaper, "Dhumketu", landed him in prison, where he endured starvation and cruelty at the hands of jailers. Yet even in chains, he mocked authority. At Hooghly Jail, under the notorious superintendent Arston, Nazrul sang parody songs to keep the prisoners' spirits alive: "Tomari jele palish thele, tumi dhonno dhonno he!" ("In your jail, polishing floors, how glorious you must be!").

Denied rice, forced to live on thin gruel, he began a hunger strike that lasted thirty-nine days. Tagore himself wrote pleading for him to relent—"Give up hunger strike, our literature claims you"—yet prison authorities suppressed the message. Only the maternal appeal of Biraja Sundari Devi finally persuaded him to break his fast. Even so, his defiance had already transformed prison walls into a theatre of resistance.

Nazrul's rebellion was never nihilistic. His songs were at once destructive and creative—tearing down the old, but also urging the forging of unity and justice. In "Chal Chal Chal" ("March Forward"), he roused his countrymen with lines that still march across history:

"March forward, brothers, march forward,

For the freedom of the country, for the salvation of the people.

Let the shackles break, let the sky be lit—

March, march forward, to the call of independence."

This was poetry as drumbeat, verse as anthem. In "Bolo Bolo Bolo" ("Speak, Speak, Speak"), he sharpened silence into weaponry:

"Speak with strength,

Let your voice be the weapon,

Shake the very foundations of unjust rule."

And in "Sarbojanin" ("Universal"), he transcended the nationalist frame altogether, envisioning a world where:

"Let there be no more division, no more pain,

Let the light of love shine through every heart,

For all men are brothers, and all lands are one."

Here was Nazrul at his most radical—not just a rebel poet of Bengal, but a prophet of humanism, collapsing borders, faiths, and hierarchies into one vast fraternity.

Born in 1899 in Churulia, now in Bangladesh, Nazrul knew the sting of poverty and hunger. Those scars carved into his verse a visceral intimacy with the downtrodden. Yet his hardships did not break him; they sharpened his words into steel. It is this union of pain and defiance that keeps his poetry alive today.

Nearly half a century after his death in 1976, Nazrul's voice has not dimmed. His verses still ignite rallies, protests, and uprisings. They are sung not only in Bangladesh, where he is revered as the national poet, but wherever injustice demands resistance. For the rebel poet did not merely write for his own time; he wrote for all time.

Kazi Nazrul Islam remains less a figure of history than a pulse in the bloodstream of resistance. His words, written by candlelight in a Kolkata room or carved on prison walls, continue to thunder against oppression. To read him today is to hear the drum of rebellion, the cry of freedom, the eternal defiance of a poet who refused to bow.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments