The endless scream

"A person can only be born in one place. However, he may die several times elsewhere: in exiles and prisons, and in a homeland transformed by the occupation and oppression into a nightmare. Poetry is perhaps what teaches us to nurture the charming illusion: how to be reborn out of ourselves over and over again, and use words to construct a better world, a fictitious world that enables us to sign a pact for a permanent and comprehensive peace...with life."

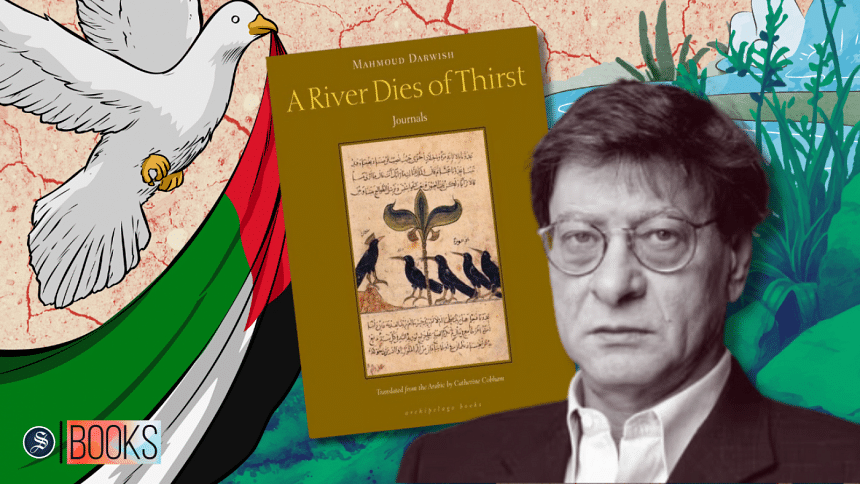

—From Darwish's acceptance speech in the Prince Claus Award, inscribed on the back cover of A River Dies of Thirst.

Mahmoud Darwish once called himself a Trojan poet, telling stories of the defeated, set upon a "map of absence" that is his homeland, Palestine. I now frequently return to the works of Mahmoud Darwish, pondering if he achieved what he had perhaps set out to do. In this tumultuous time, I re-read his final collection once more and the answer was a resounding yes. He undeniably did.

A River Dies of Thirst was the last collection to be published in Arabic before Darwish's death. Written in 2006 and translated by Catherine Cobham, this collection is a blend of journal entries, prose poems, completed poetry and sometimes fragmented thoughts. Some are written in free verse, and some in prose. These seemingly dichotomous forms of narrative perfectly blend under the magic of his hands. He grapples with violence, trauma, politics, fame, and sometimes abstract concepts. He also writes about writing. When I first read this book years ago, I might have liked the abstract ones more. Time often dictates how we feel about certain works. Re-reading now, his narration of the experiences in exile, in occupation, in refugee camps is what I appreciate more.

The collection opens with poems describing the anguish of war-torn Gaza. His writing captures what it takes to be an ordinary citizen in a country ripped apart by violence. The gravity of ostensibly ordinary casualty is portrayed, so we don't become desensitized to any form violence. He writes "The house as casualty is also mass murder, even if it is empty of its inhabitants"

Humanity and satire are juxtaposed from one poem to another. Satire drips in his voice as he says, "When they went down the road of sympathising with the killer, some foreign tourists passing by asked them: 'What has the child done wrong?' They answered: 'He will grow up and frighten the frightened man's son.' 'What has the woman done wrong?' They said: 'She will give birth to a memory.'" It's probably unwise and somewhat futile to try to distinguish his work from politics because the personal is political. The endless cycle of suffering of Palestinians comes up again and again throughout this collection.

"Clear skies. Calm blue sea. Northerly winds. Good visibility. But the autumn clouds the symbolic name for killing—wipe out an entire family, made up of seventeen lives. The news searches for their names under the rubble. Apart from that, a—normal life appears to be running its normal course. The Devil still boasts of his long quarrel with God. Individuals, if they wake up alive, can still say 'Good morning,' then go off to their normal jobs: burying the dead." This is what Darwish writes about the routine of burying the dead. His poems ring true now more than ever, showing why he continues to be the poetic voice of the Palestinians.

Far from the onslaught, my morning routine begins with a perusal of the headlines. How many casualties have been reported as of late? At night, I'll tally up the number of children that died in Gaza. We talk in numbers. On breaking news, people are reduced to statistics. Breaking news counting dead bodies no longer is breaking news. It falls into a routine. When violence happens at such an overwhelming rate as is happening now in Gaza, it's easy to become desensitised to it.

I read Darwish's A River Dies of Thirst again to remind myself how the violence is devastating every time. People are not numbers—they're humans with feelings, home, families. As the title of this piece hints, I find myself returning to the opening poem of the book on a frequent basis to spare myself from being desensitised to the violence that Palestinians are enduring on a regular basis. So, I keep remembering to speak up for the oppressed without the fear of sounding "political". I have ingrained Darwish's words in my heart:

"Father! Let's go home, the sea is not for people like us!'

Her father doesn't answer, laid out on his shadow

windward of the sunset

blood in the palm trees, blood in the clouds

Her voice carries her higher and further than the seashore. She screams at night over the land

The echo has no echo,

so she becomes the endless scream in the breaking news

which was no longer breaking news when

the aircraft returned to bomb a house with two windows and a door."

Sadika Nousheen is a law student at the University of Dhaka.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments