Tariff math favours Bangladesh in shifting US trade landscape

When US President Donald J. Trump burst back onto the global trade stage, he brought with him a term that's now rattling old-school trade economists: reciprocal tariff. Think of it as "you charge us this much, we'll charge you the same"—a tit-for-tat pricing game that bypasses the World Trade Organization (WTO), the traditional referee of global trade rules.

While this move has left WTO purists in a daze, for some countries—Bangladesh included—there is a silver lining.

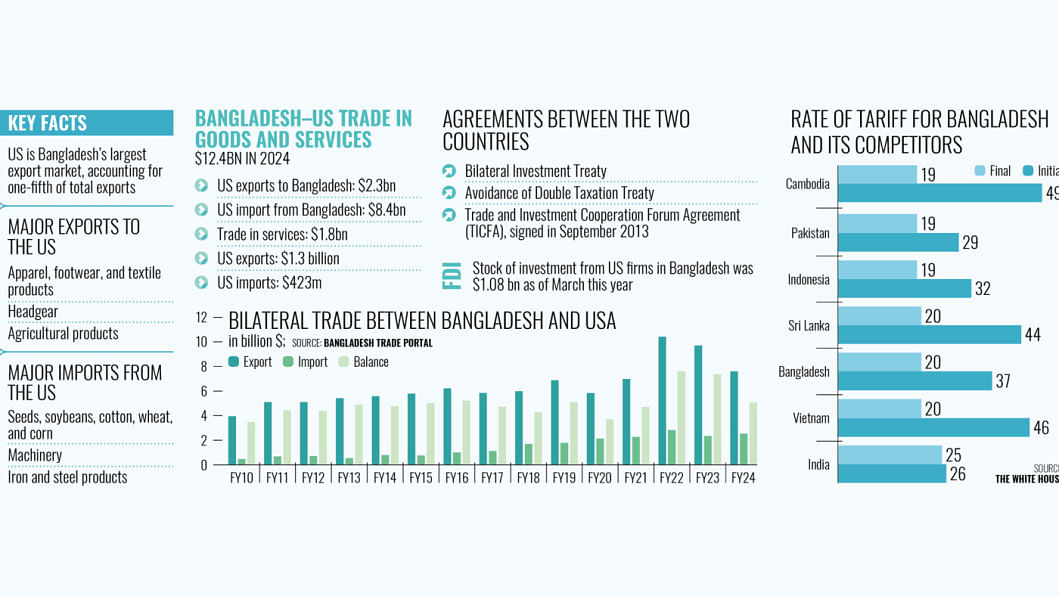

After lengthy negotiations with the United States Trade Representative (USTR), the American government's chief trade negotiation body, Bangladesh has secured a 20 percent reciprocal tariff rate on its exports to the US. Add that to the existing 16.5 percent average US import duty, and you get a new effective tariff rate (ETR) of 36.5 percent, according to the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA).

Sounds high? Perhaps. But it's all about comparison. In a world where competitors are being slapped with tariffs as high as 50-60 percent, 36.5 percent starts to look like a discount.

A COMPETITIVE EDGE

In 2024, Bangladesh held 9.3 percent of the $85 billion US apparel market, a figure that could now rise significantly. Why? Because the reciprocal tariff system affects different countries in dramatically different ways, and for Bangladesh, it happens to be largely favourable.

The government and local private-sector entrepreneurs are optimistic. The new tariff rate is much lower than what other competing countries such as Vietnam, India, and China are facing. They have already noted that the new ETR will help boost Bangladesh's exports to the US, as American clothing retailers and brands will prefer Bangladesh as a sourcing destination due to its competitive tariff edge.

AK Azad, managing director of Ha-Meem Group, a major garment exporter to the USA, said the reduction of the tariff is a relief for him.

However, his American business partners are demanding a share of the additional tariff burden, which is squeezing his profit further. "It will take more time to absorb the additional tariff by the importing companies in the USA," he said.

Mahmud Hasan Khan, president of the Bangladesh Garment Manufacturers and Exporters Association, is also hopeful that exports from the country will rise because of the tariff benefit.

"If the local suppliers are not aware, the international retailers and brands may put pressure on them to share a certain portion of the additional tariff," he said.

HOW WE FARE AGAINST COMPETITORS

Vietnam, Bangladesh's close competitor in the global apparel market, currently enjoys an 18.9 percent share of the US market and faces a similar 20 percent reciprocal tariff. But the devil is in the details.

Vietnam's export portfolio to the US consists largely of high-end, synthetic garments (activewear, skiwear, and outerwear), which already attract an average 32 percent US duty. Add the reciprocal tariff, and the effective tariff rate could easily exceed 50 percent.

Moreover, President Trump imposed an additional 40 percent tariff on garments found to be transshipped through Vietnam to avoid Chinese duties. Since Vietnam's garment sector relies heavily on Chinese raw materials, investment, and supply chains, this adds another layer of complexity and cost, potentially eroding its competitiveness.

India, another major competitor with a 5.9 percent market share in the US, has been hit the hardest. Trump slapped a staggering 50 percent rate on the country due to its continued import of Russian oil. That is the highest tariff rate among all countries in this new regime. Considering India's average tariff on garment items to the US, its ETR now stands at 66.5 percent.

Then there's China. The world's largest apparel supplier, with a 20.8 percent share of the US market, is facing a steep 55 percent ETR, which may climb higher as US-China tariff negotiations remain unresolved.

The East Asian economic superpower has been steadily losing ground in the American market since 2018, when Trump launched a trade war during his first term in office. Since then, countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Pakistan, and India have begun carving out bigger shares.

Indonesia faces a 19 percent reciprocal tariff, resulting in a 35.5 percent ETR, giving the country a comparatively advantageous position over Bangladesh.

BANGLADESH'S SECRET WEAPON

What gives Bangladesh the edge? Cotton.

Its five top garment exports—trousers, knitted polo shirts, woven shirts and blouses, sweaters, and underwear—together account for 80 percent of its total apparel exports to the US. The concentration of cotton fibre in all these items is particularly high. And in the US tariff regime, cotton garments are treated far more leniently than synthetic ones.

This puts Bangladesh in direct contrast with Vietnam and China, who are more dependent on non-cotton and high-tariff products.

There's more. Under Trump's executive order, if an export item contains 20 percent US-origin content, such as American-grown cotton, the 20 percent reciprocal tariff is waived on that portion of the product's value.

Here's what that means: A $10 shirt made in Bangladesh using 20 percent US cotton will have the 20 percent reciprocal tariff applied to only $8 of its value, not the full $10. Some Bangladeshi exporters are already using up to 40 percent US cotton, meaning they'll enjoy even lower ETRs.

In the near future, there is a possibility of using more US content as Bangladesh has already agreed to import more American cotton and build warehouses for American cotton.

Exporters expect exports from Bangladesh to the US to grow because of this competitive edge.

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

Even with this competitive edge, a cloud looms over the celebrations: the US apparel market itself is shrinking.

"Just a few years ago, the US imported $105 billion worth of apparel annually. In 2024, that number dropped to $85 billion. And now, it could fall further, to $75 billion due to the higher tariff rate," said Mohammad Abdur Razzaque, chairman of the Research and Policy Integration for Development (RAPID).

No matter how favourable Bangladesh's tariff rate is, it won't matter if there are fewer orders coming in.

Before the introduction of the reciprocal tariff, the US's average import duty was 2.2 percent. The leap to 20 percent overnight is likely to fuel inflation, affecting consumers' purchasing power and leading to reduced spending.

The tariff burden, ultimately, falls on the consumer. Importers pay it initially, but it shows up in the price tag. As costs rise, American shoppers may scale back. And when retailers cut orders, even countries with favourable deals, like Bangladesh, feel the pain.

So where will all the surplus go?

The obvious answer is Europe. But that presents a new challenge: oversupply.

"Too many suppliers will compete in the same markets, and the European buyers may ask for price cuts because of unhealthy competition by the supplying countries," said Razzaque.

WHAT BANGLADESH TRADED FOR THE DEAL?

The reciprocal tariff agreement didn't come without strings attached.

Currently, the trade gap between the two countries is $6 billion, whereas Bangladesh exports goods worth $8.2 billion and imports goods worth $2 billion from the US.

To win a lower ETR, Bangladesh had to agree to a shopping list of US demands during negotiations, including buying more American goods—such as aircraft, wheat, soybeans, cotton, and other agricultural exports—to reduce the trade gap.

Bangladesh also agreed to open up its domestic market to US dairy, meat, and poultry industries, where local producers, especially small and medium enterprises, will now face stiff competition.

During the negotiation, the USTR also asked Bangladesh to reduce its dependence on China for procuring industrial raw materials—a tall order, considering China is the largest trading partner of Bangladesh. Local entrepreneurs import nearly $20 billion worth of goods a year from China.

Bangladesh is also set to undertake significant policy and regulatory reforms, including removing foreign ownership restrictions, streamlining investment approvals, and improving transparency for American investors.

The pending agreement is expected to broaden this engagement beyond apparel, into sectors such as agriculture, energy, aviation, and infrastructure.

Bangladesh will have to ratify several international agreements, including the Berne Convention (copyright), the Brussels Convention, the Budapest Treaty (patents), the Marrakesh Treaty (accessible books), the Singapore Treaty, the WIPO Copyright Treaty, the Patent Law Treaty, the Hague Agreement, and the Paris Convention, among others.

But the mood in Bangladesh is optimistic so far.

"This is a very good negotiation, and it is expected that the shipment of goods from Bangladesh will increase as the country has comparative tariff benefits over other countries," said Commerce Secretary Mahbubur Rahman, who was an integral part of the negotiation.

Apart from garments, the export of other goods—such as shoes and leather and leather goods—will also increase to the USA because of the lower tariff benefit, he also said.

The new reciprocal tariff regime of the world's largest economy presents a new phase of global economic diplomacy. In the end, it's a very delicate balancing act. Bangladesh has managed to turn a turbulent moment in US trade policy into a potential advantage. But it's a narrow path. The tariff rate may be lower, but the stakes are higher than ever.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments