A green shoot of hope in a (still) arid, racist terrain

The USA's battle against racism continues to be a Sisyphean struggle. No sooner do you bask in the comforting awareness of the enormous strides the nation has taken than you are yanked by the scruff of your neck to face some dreadful sign that this ugly affliction is well and alive.

For once, this truism has been turned on its head. On November 24, a jury of eleven White members and one Black member—this, oddly enough, in the Black majority township of Brunswick in the deep South state of Georgia—returned a stunning verdict in a murder case. Members of the jury found all three White men guilty of murder in the shooting death of a Black man whose only evident crime appeared to be jogging in a White neighbourhood a few streets away from his home.

It may seem like an open-and-shut case, but the verdict is stunning because this is the deep South, where in many parts of the state public sensibility is still deeply marinated in a noxious pickled history of slavery, confederacy and egregious racist Jim Crow laws.

This is the deep South, the setting for Harper Lee's searing Pulitzer Prize-winning novel To Kill a Mockingbird, set in the 1930s, where an all-White jury falsely convicted a Black man of rape in neighbouring Alabama, despite powerful exculpatory circumstantial evidence.

The verdict comes at a time of nationwide outrage at the recent history of police shooting Black people to death, often with impunity. A BBC timeline lists 11 high-profile cases since 2014 where police were involved in such killings. This includes the case of George Floyd, whose gruesome killing drew international protests. Only in four instances were officers prosecuted. In one of those cases, the involved officer was cleared of murder charges. (The Georgia murder is not included in this list, as the convicted murderers did not belong to law enforcement.)

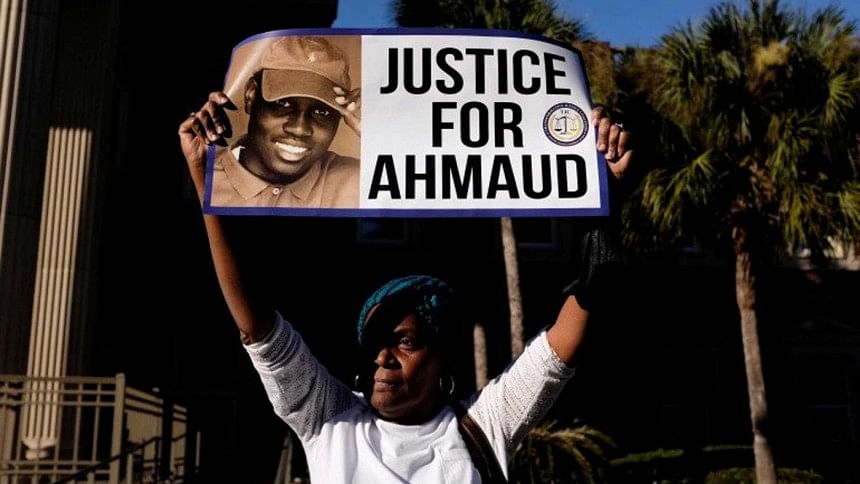

So it is remarkable that the jury found Travis McMichael; his father, Gregory McMichael; and their friend William Bryan—all White—guilty of felony murder offences after the trio chased down and then shot to death Ahmaud Arbery, a 25-year-old Black youth, in Brunswick, Georgia, in February last year.

What transpired before the case came to trial is even more remarkable. Arbery was killed in February, several months before the killing of George Floyd, the international cause celebre. Although police had immediate access to a cell phone video of the murder, absolutely nothing happened for months. Even when the case went into trial, there was far too much doubt about the eventual verdict. The facts of the case are brutally simple: On an unfounded suspicion of burglary for which the armed defendants had no evidence, they pursued the unarmed Arbery. When Arbery tried to flee, he was cornered and shot to death.

Local police and prosecutors base their refusal to arrest on the preposterous claim that the defendants killed in self-defence. It was only after the murder video went viral on social media and resulted in a statewide—and eventually nationwide—outcry that Georgia's Republican Governor Brian Kemp stepped in at the request of local authorities and brought in the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, a state agency. The GBI started an investigation and arrested the three defendants.

It took a full 77 days since the murder for the three defendants to be arrested. Notwithstanding this ignoble record, there are signs of heartening changes.

First, a little historical note is in order. Georgia, like most other formerly-Confederate southern states had shifted lock-stock and barrel to the Republican Party after the landmark passage of the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act in the 1960s by Democratic President Lyndon Johnson. Republicans vehemently deny this, but there has been a long history of racially charged politics in Republican campaigns. This ranges from the "strapping youth" and "welfare queen" snarks of President Ronald Reagan to the elder President George Bush's notorious campaign ad highlighting paroled murderer—and surprise, surprise Black—Willie Horton.

To his credit, Kemp, Georgia's Republican governor, responded to the crisis with alacrity and welcomed the verdict. "Ahmaud Arbery was a victim of vigilantism which has no place in Georgia," Kemp said in a statement.

This is a welcome contrast with another Southern governor at another time. After Medgar Evers, a Mississippi activist with the Black civil rights organisation NAACP, was murdered in 1963 by the segregationist White Citizens Council member Byron De La Beckwith, Democratic Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett actually met and shook hands with him during his trial. (Despite overwhelming evidence, White juries failed to reach a verdict twice. Beckwith lived a free man for three decades until he was finally tried and convicted in 1994.)

Compared to the Evers murder, the verdict on Arbery's murder has been relatively swift. Yet it is a bittersweet moment for many.

Rev. Raphael Warnock, a Democratic US senator from Georgia, issued a poignant tweet: "This verdict upholds a sense of accountability, but not true justice. True justice looks like a Black man not having to worry about being harmed—or killed—while on a jog, while sleeping in his bed, while living what should be a very long life. Ahmaud should be with us today."

It is a heartbreaking observation. What gives me some hope, however, is that it comes from someone duly elected US senator from a deep South state despite being "a fitting heir to the mantle once worn by The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr", according to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

It is also sadly true that this hope is diminished by the fact that the path to justice for Arbery was unconscionably tortuous. It is a sobering reminder of how much remains to be done.

As Adam Serwer trenchantly observed in The Atlantic magazine: "To say the system worked in this case is like saying your car made it home—after your entire family had to get out and push it miles down a dirt road."

Ashfaque Swapan is a writer and editor based in Atlanta, US.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments