How Gen Z kept connected after the internet shutdown

July 18, 2024. 9:00 PM. Bangladesh experiences a complete internet shutdown. No broadband. No mobile data. In an instant, one of the most densely populated countries completely vanished from the rest of the world.

The blackout came as student protests, initially triggered by a controversial government quota policy, escalated into a mass uprising. As tensions rose in Dhaka and other major cities, the government moved to cut off the one thing young people relied on most: the internet.

Yet, instead of discouraging or slowing them down, the shutdown only made the youth more anxious, and even more determined.

One of the major forces behind the July movement was Bangladesh's apolitical youth, mostly from Generation Z. Despite facing such a significant hurdle, they rose to the challenge of staying connected with their loved ones. They adapted: quietly, ingeniously, and often without leaving a digital trace.

A different kind of network

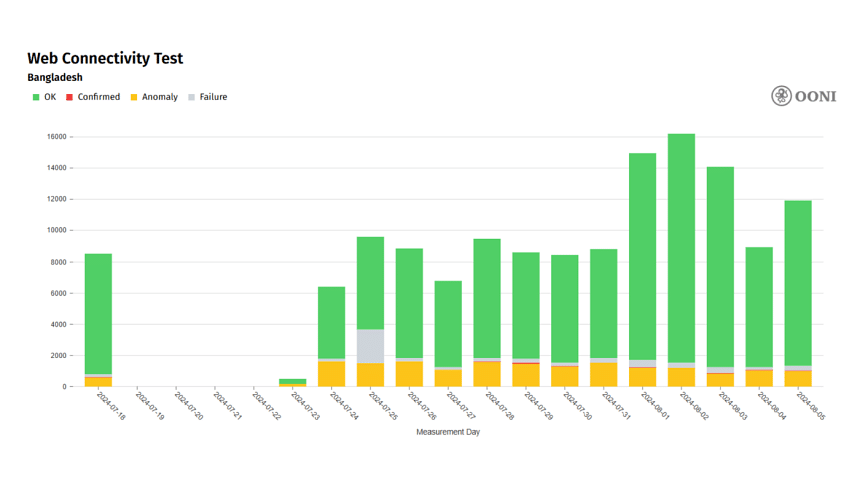

Data from OONI, one of the world's largest open dataset on internet censorship, confirmed what many already knew that from July 18 to July 23, 2024: Bangladesh was under an internet blackout. Internet disruptions and blocks intensified in the days that followed, as the student-led uprising continued until August 5, 2025. Yet even as the government pulled the plug, young people found ways to communicate, organise, and resist.

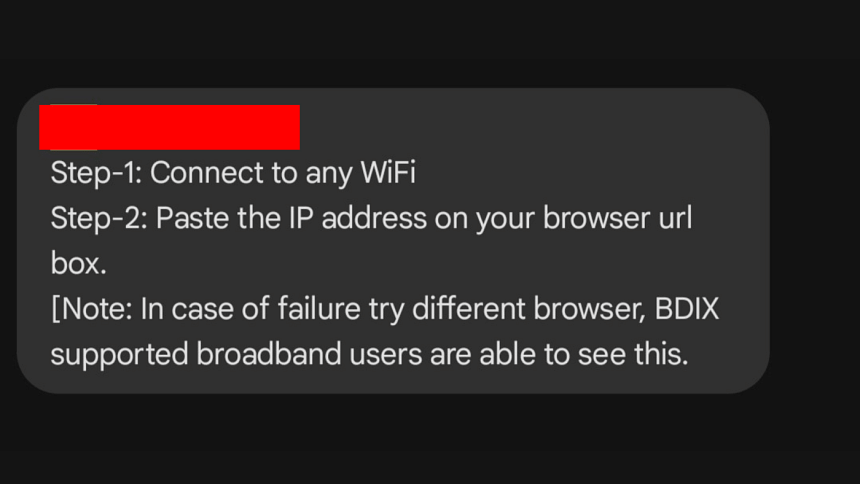

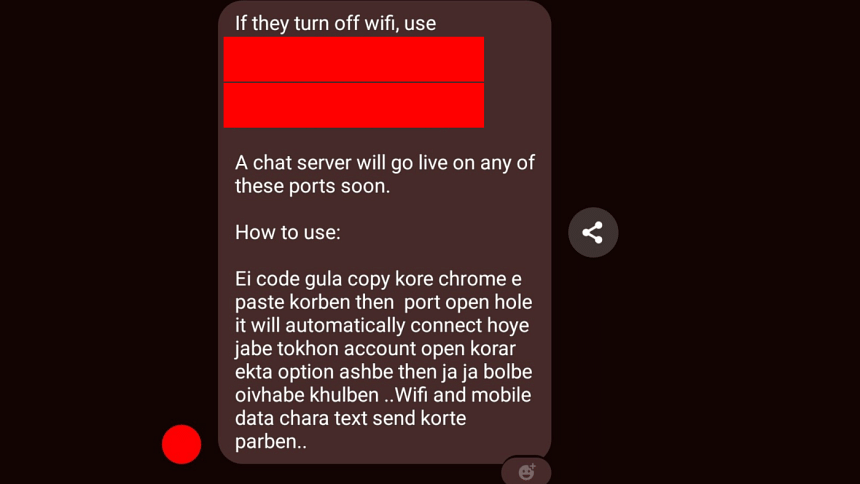

One of their oldest tools was the BDIX, Bangladesh's domestic internet exchange system. While access to the global internet was blocked, local area networks (LAN) in dormitories and residential areas remained alive. Using Wi-Fi connections with no internet, students connected to shared BDIX servers, many of which had quietly existed for years.

These servers were reconfigured almost overnight. They became hubs for updates, encrypted meeting points, and even makeshift newsrooms. Some were used to store short news clips and protest instructions. Access was not centralised, and most of it spread the old-fashioned way: word of mouth. It was a digital underground without the internet.

Planning in plain sight

When mobile data vanished, the fallback was voice calls. But even those were laced with caution because of surveillance from the government. Students used code words to share rendezvous points.

The first thing many youths did when the internet returned was not to post their experience but to prepare for the next blackout. More servers were created. More local apps were downloaded. Communication channels became more decentralised. And everything was done with the understanding that it could all vanish again at any moment.

Apps without internet

While BDIX networks filled one gap, apps like FireChat, Bridgefy, and Briar offered another layer of connectivity. These platforms work by creating mesh networks which are basically chains of devices linked via Bluetooth or Wi-Fi, where each phone acts as both sender and router.

FireChat, which gained global fame during the 2014 Hong Kong protests, proved especially popular. Bridgefy, another mesh networking app, offered a slightly more structured approach with its three modes – person-to-person, broadcast, and mesh, which enabled real-time communication within roughly a 100-metre radius. Meanwhile, unlike FireChat and Bridgefy, Briar could sync messages over Tor, and did not rely on any central servers. Everything stayed on the user's device.

These apps were not perfect because of their vulnerabilities. Still, for many in the streets, the benefits outweighed the dangers. With each new user, the network expanded.

Memories of a lost week

As the protests swelled into August and tensions deepened, many young people began to document what they would experience – not just through videos, but in journals, artwork, and voice notes. For them, the internet blackout was not just about the loss of the internet, but the discovery of something else: the power of human connection and trust, even in silence.

What happened in Bangladesh during those weeks in 2024 was deeply traumatising, as people were being shot and killed in the open streets. Gunshots, fire, and violent clashes were everyday incidents. Yet amid the chaos, what stood out was the quiet resilience of the country's youth. The apolitical generation took to the streets, shouting at the top of their lungs in protest against the widespread killings happening around them. It was an experience that defied explanation - one that could only be understood by living through it.

With no central command, no political affiliation, and no playbook, the apolitical Gen Z in Bangladesh stitched together an improvised communication network, spanning apps, servers, phone calls, and shared understanding. It was not flawless. It was not always safe. But it worked.

And in the quiet hum of servers, the Bluetooth signals bouncing between phones, and the whispered plans at tea stalls, they found a way to stay connected. Not just to each other, but to something larger. A future where silence would never mean surrender.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments