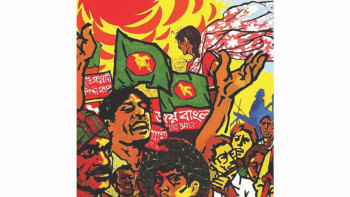

March 1971 as witnessed by women

The entire month of March in 1971 stands etched as a profound turning point in the birth of Bangladesh. The harrowing events of March 25th in Dhaka bore witness to a deliberate onslaught by the Pakistani army upon unarmed civilians, leaving an indelible mark of trauma upon the collective consciousness.

Beyond objective narratives, the subjective retelling of survivors is imperative for comprehending the true extent of the atrocities endured. Among them, three extraordinary women offer firsthand testimonies providing invaluable insights into the struggle and the unwavering resilience displayed by the people in the face of unparalleled adversity.

General Yahya Khan's abrupt suspension of the National Assembly session led to the non-cooperation movement across East Pakistan. Makhduma Nargis, then a civil medical officer at the Pakistan Air Force, chose to join the movement instead of going to work. Reflecting on her commitment, she remarked, "Every day, people would march from Dhaka Medical College to Paltan." Makhduma, an active member of the Student Union and Mohila Parishad, emphasized the crucial role of organizations like Mohila Parishad, led by poet Sufia Kamal, in uniting women of all walks to accelerate the movement.

"Baba placed the table clock on the table after gathering the rest of the members in the same place, and our eyes were fixed on it while sitting around. There were sounds of firing, and in between, everything became eerily silent. In those quiet moments, the sound of the ticking—I never experienced the sound of a clock to be so terrifying; I experienced that day."

The stirring speech on March 7 rallied millions, unified in the quest for freedom. Following the speech, students, both boys and girls, commenced armed combat training with dummy rifles at the Dhaka University playground. As a teenage girl, Dr. Nazma Shaheen, now a professor at the Institute of Nutrition and Food Science, University of Dhaka, underwent armed training under two retired Bengali Army personnel at Kola Bhaban. "Besides the political exposure, I always felt the spirit of freeing the nation," recalled Nazma Shaheen, reminiscing about training sessions that included strategies for taking control of enemy camps and weaving flags in the morning of March 25. Following the university training, female student leaders dispersed to various colleges and organized training sessions for girls.

Dilara Mesbah, now a writer, described the entire situation as perplexing, reminiscing, "In our Gopibagh home, discussions about the political situation and circulating rumors took place quietly behind closed doors. Meanwhile, my four sisters-in-law were sent to the village for security, leaving only five of us there."

Then came the night of March 25th when the gates of hell were cast open.

"That night, we were all engaged in our usual nighttime activities. It was around 10 pm; mothers were chatting, and I was sitting with a friend on a slipper near Fular Road," said Nazma Shaheen. Upon learning about the approaching convoys of Pakistani tanks and truckloads of soldiers towards Dhaka University, Ahmed Sharif, professor of the Department of Bangla, rushed to circulate the information to students leaving the hall and instructed Nazma and her friend to tell their mothers to go home. Along with Prof Sharif, Nazma's father, then the secretary of the Fular Road Para Association, tried their best to inform university quarters not to light up rooms and to avoid peeking through windows while firing. Her sister and Nazma went to sleep while waiting; suddenly, the artillery and the vicious clatter of machine guns woke them up. "Baba placed the table clock on the table after gathering the rest of the members in the same place, and our eyes were fixed on it while sitting around. There were sounds of firing, and in between, everything became eerily silent. In those quiet moments, the sound of the ticking—I never experienced the sound of a clock to be so terrifying; I experienced that day," she added, then residing at 17/A Fular Road.

Makduma recalled people in the locality, political and apolitical, started hastily assembling a makeshift barricade of tree stumps across the road, unaware that they would soon face tanks. "As our house was beside the road, flashes of light emanated from the Razarbagh police line as a battle erupted, where the police force fought with all their might. From pin-drop silence to the sound of artillery and the vicious clatter of machine guns, the atmosphere transformed drastically. I held my nine-month-old close to my heart, cramming 12 people into the stair passage, while pondering what was happening at the police line. My promise as a physician and a Bengali weighed heavily on my mind, contemplating handing over my child to someone and going to the police line to help," said Makduma.

Nazma Shaheen and her sister thought they would share their experience with fellow members the next day, recalling the memory as teenagers unable to decipher the actual reality until the next morning. As the light grew, they heard gunfire and saw firing in the rooms of Iqbal Halls on the morning of March 26, peeking from the upper portion of the curtain.

Shaheen witnessed corpses brutally killed and stabbed multiple times with bayonets in the fields of Jahrul Haq Hall while traveling to Azimpur with the family on the morning of March 27 upon the lifting of the curfew. "Since nowhere was seen to be safe as we headed towards Jinjira," said Shaheen.

Dilara, accompanied by her family members, embarked on the journey of leaving the city while holding her 4-month-old baby.

Makhduma also became part of the throng of people leaving her home behind. She had to leave without her husband on the same day, only to reunite with him at the Agartala refugee camp months later.

Saudia Afrin is a journalist at The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments