Reclaiming Spaces

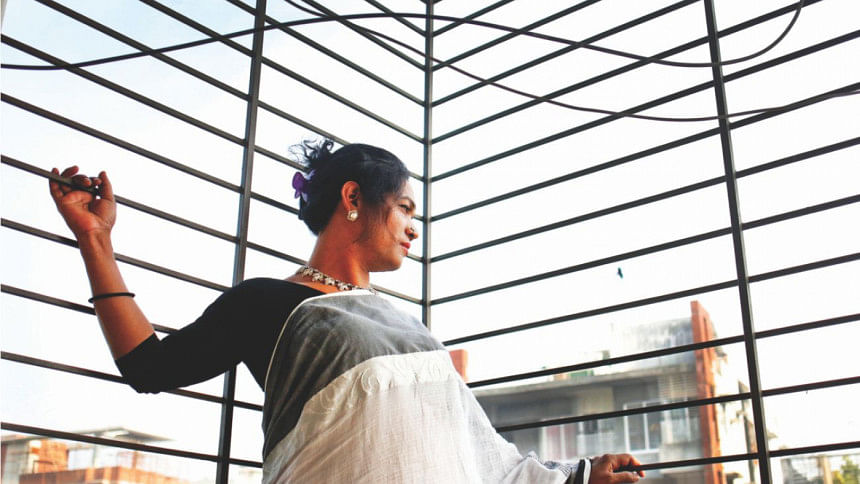

Munni, Artisan, Logos

Though the government has made an announcement to recognise our gender identity as "Hijras" or "Third Gender" in 2013 and promised to rehabilitate us by appointing 12 of us in government jobs in the first phase, they have failed to keep their promises so far. When we were going through the medical tests for the job, the doctors of the government hospital refused to touch us and instructed their assistants to strip us stark naked in the middle of the examination hall in front of everybody to "conduct the test". Later they reported to the Social Welfare Department that we are all full grown "men" and not "hijras" because of our genitalia. The government should have known that they cannot define gender by what genitalia a person is born with. They should also have appointed specialists in the medical board who would actually understand our identity.

Nine of our community members are extremely lucky to have found a job in this factory where we make bags and shoes. But that's just nine of us. What about the rest of our population? We used to go out and collect a small amount of money from the shops and from the streets to earn money for our existence. But now, people refuse to give us even that very small amount of money saying why don't we get a job and work like "normal" people since the government has recognised us. But our question is who would give us those jobs? Them or the government? Both the parties have only given us hope but failed to keep their promises. Where will we go? We are capable of doing anything like any other human being. We want to be a part of the mainstream workforce and help to develop our country like everyone else and live with proper dignity. Is it too much to ask?

Joya Sikder, President, Somporker Noya Setu

I worked with a bunch of different NGOs before I formed my own organisation to fight for the rights of people coming from different sections of gender and sexual minorities. When I first joined an international NGO in Bangladesh, my office colleagues refused to communicate with me about anything except work issues, or to sit with me at the same table during lunch. A lot of women from that organisation also refused to let me use the women's toilet in that office. Because, in their perception, I am not a man or a woman and I am a Hijra which is supposed to be a bad thing (however, I Identify as a transgender-woman and not a hijra since I am not engaged in "Hijragiri", nor am I directly a part of the Hijra community). They were scared of me and I could see the fear in their eyes. It took me a while to change their misconceptions and fear about me or human beings like me in society with my logical explanations, and to bridge that distance between them and I—which wasn't created by me in the first place. I have faced this kind of discrimination in my own home, my own locality and in my own country, everywhere, from almost everyone.

Now I work not just for transgender people or Hijras but for all the people coming from a diverse gender and sexual identities because I have experienced what they go through since I went through the same discrimination and pain, and I still do in many ways. I hope one day the government and society would create more spaces to discuss about these issues and spark conversations, create constructive discourses, laws and legal frameworks to protect our rights as a human being like any other citizen of the country. Until then, I would keep resisting all these discriminations with my courage and knowledge which are the biggest powers of my life.

Shobha Sharkar, Junior Advocacy Officer, BLAST

I have come a long way to earn my dignity and prosperity from society. It didn't happen just because people (of society) were kind to me and helped me with my ambitions and dreams, but because of my hard work, skills, honesty and determination to be where I am today. Of course, I needed help from many people to reach this place, who doesn't? But I refuse to accept that my community or I am a subject of anybody's pity. We wouldn't have needed sympathy to survive and secure our positions, if society had not first, forcefully taken away our space from us, and then made it look like they are our saviours and we would not have survived without them. To me it is more like they are now slowly giving back a tiny percentage of our space back to us, the space that was ours to begin with!

Ivan Ahmed Katha, Artist-Activist, President, Shachetan Shamjasheba Hijra Shanga

Back in my school days, I was singled out by my teachers and made to stand in the middle of the field with a small piece of brick on my head to shame me for being a "girly man" and "cure" me so that I can become a "real man". I remember going through this process many times in my life and I couldn't even go tell my parents about this since I knew they think the same about me and they would reprimand me if I had complained about it. I didn't have anyone to talk to and tell them that I am not a man to begin with, I am a woman. I used to talk to my reflection in the mirror since I felt that image in the mirror was the only thing that understands me.

When I finally left home, I did hijragiri for a long time before I started to evolve as a human rights activist and a cultural personality. Since then, I have worked very hard to develop my skills as a human rights activist, dancer, writer, poet and theatre activist and have represented and worked with many famous human rights-based platforms. Till now, I have staged many dramas which are written by me and am the only hijra dancer enlisted under the Shilpakala Academy. I dream for a day when I will not be the only one doing these things and will be able to create space for other people like me in society so that they can also explore their dreams and live as a dignified human being, the dignity that we deserve like anyone else in society.

S Srabonti, General Secretary, Shachetan Shamjasheba Hijra Shanga

Like everyone else in my community, I had to leave my home at a very young age, when I was in college, because of family members and society who didn't want to accept me the way I am. Since then, my mother has been the only person who was in touch with me and still loved me. After my parents' death, I reconnected with my brothers and sisters, and I go visit them once or twice a year, mostly on my parents' death anniversaries. But I still can't meet them in my own village home in broad daylight. I can only see them at night, wearing men's clothes and only for a few hours. I feel very humiliated when I do this, but I still do this in order to stay in touch with my siblings—I love them regardless of everything. Sometimes I wonder whether we were created only to suffer the pain caused by everybody. I wear a smile whenever I go out of the house, but I can't describe the intensity of the pain that I go though in words.

Comments