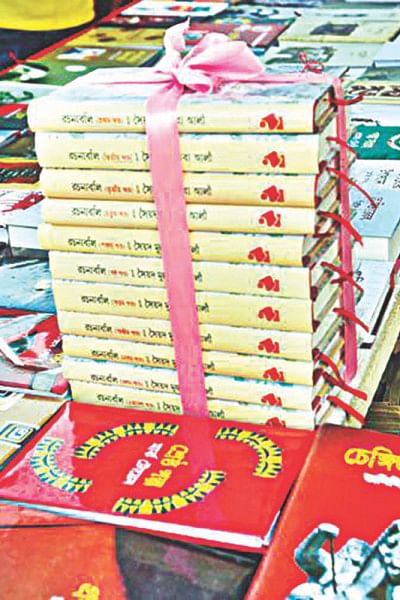

Publishers prepare for the Boi Mela

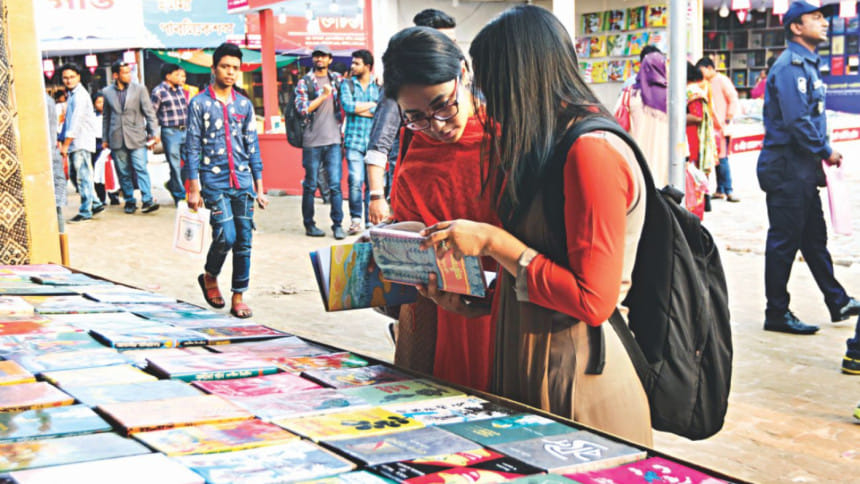

February is synonymous with a string of cultural events, but none perhaps as iconic as the Ekushey Boi Mela, a month-long commemoration of the 1952 Language movement that takes over Suhrawardy Udyan and Bangla Academy. What started out as a modest display of books by Muktodhara Prokashoni by the Bangla Academy south gate in 1974 has grown, over the decades, into the literary highlight of the year.

Not to suggest that this is unique to Bangladesh; the 2017 Global Book Fair report by the International Publishers Association notes that book fairs are necessary as a platform where readers and authors directly interact, publishers and retailers network, and the media pay attention. But while book festivals the world over allow readers to discover what has been published throughout the year in addition to the featured releases at the time of the event, the Boi Mela is unique in that it draws writers and publishers alike to plan specifically for the month of February.

By the numbers

“I wouldn't say that the Boi Mela gets more response from readers than the rest of the year combined, but roughly 50 percent of our annual turnover comes from the month of February,” says Farid Ahmed, publisher of Shomoy Prokashoni and president of the Academic and Creative Publishers' Association of Bangladesh.

Mashfique Tonmoy, publisher of Boshadupur Books, concurs, comparing their release of 50 books at Boi Mela this year to the five or six titles released throughout the rest of the year. You'd normally expect this to hamper business the year-round, but as Mashfique explains, their sales over the remaining 11 months is actually carried by the popularity of the titles released in February.

Ahmed Sarwerruddawla, managing director of Academic Press and Publishers Library (APPL), agrees that as publishers, their yearly work builds up to the fair. But, he says, sales are not as high as expected. “People come here in great numbers, but they buy very little.” His own publishing house saw approximate sales of BDT 3 lakh during Boi Mela last year while his overhead costs alone were around a third of that.

“It's not about how many books we brought out, but how many good books we brought out. There is an expectation that everything has to be released at the fair. That creates an unfair pressure on the publishers and authors,” says Mahrukh Mohiuddin of University Press Limited (UPL).

What sells?

“Some publishers who get good business at this time are those who have very popular writers. Others who see profit are where writers themselves invest to get their books published,” says Hossain.

Sales also depend on the genre. Each year, the response from readers—the books they search for and the writers and topics they ask about at the fair—allows publishers to plan the following year's content.

Shomoy Prokashoni plans for a spread of 10-15 genres of books including memoirs, travelogues, interviews, novels, poetry, cookbooks, and war literature. Depending on the number of books under each subject, they accept and commission manuscripts from both known and new writers.

Despite the wide offering of genres, fiction, and novels in particular, remain most popular among readers at the festival for Borshadupur and Ananya. Poetry seems to be on the decline, and thrillers and science fiction seem to be garnering particular attention this year. Certain genres, or specific books or authors, often stay in the limelight throughout the rest of the year because of the publicity gained through media coverage during the Mela.

According to Sarweruddawla, collections of poetry and short stories are the most popular, followed by children's books, and then novels. APPL is coming out with 35 new books this year—by both established and new writers—including memoirs, children's books and even a self-help book in English.

Others target specific audiences. Ananya Prokashoni, for instance, tries particularly to attract young readers like elementary and middle school children in an effort to expose them to Bengali literature. “We especially try to make stories about our Liberation War attractive to young readers, so that the younger generation can learn to take pride in our history,” Md. Monirul Huq of Ananya tells Star Weekend.

Reading patterns have changed though. “Our book culture hasn't developed over the years, rather reading habits have weakened,” says Hossain.

Reaching readers

Publishers and writers largely promote books ahead of the Boi Mela on social media. Writers, publishers, and their friends have been sharing descriptions and snaps of their books on Facebook especially. “Social media has made everything easy,” says Hossain.This is echoed by Borshadupur Books, which relies mostly on digital media publicity now.

Others disagree, saying social media reach varies. “Industry-wide, digital marketing is low,” says Sarweruddawla. “Earlier, word of mouth used to be valuable. Readers would also come seeking books they had seen in libraries and read reviews of in the papers,” adds Hossain.

Newspaper ads, especially in the literature pages, is another traditional medium publishers rely on. But this is out of reach for some publishers, such as APPL. Instead, what they can afford to do, is take out ads in the newspaper that comes out at the fair everyday (complementary copies of which are given to visitors).

Monirul Huq, meanwhile, explains how getting coverage for new writers in the mainstream media proves difficult, as newspapers tend to show more interest in the upcoming works of well-known writers.

As a result, much of the book publicity these days occurs through boosted social media posts, readings and informal sessions organised by the authors, and through word of mouth. Once readers reach the fair, they discover books from the catalogues at each publishers' stall and the pamphlet brought out by the Bangla Academy.

On new writers and the practice of 'self-publishing'

Shomoy Prokashoni finds many of its new writers when they commission manuscripts through media announcements. Meanwhile, Hossain says that they discover new writers if someone writing on a public forum (such as in the newspaper or a magazine or even a status on Facebook) catches their eye, and through others' reference. “In the last decade, we have introduced at least 50 new writers.”

Hossain explains that the publishing process can involve work on a manuscript for years, if necessary. “Books which aren't ready, quality-wise, I will not send for publishing, no matter how much the writer wants it out. We only go to publication if we feel it is suitable to go to readers,” he says.

Tonmoy of Borshadupur says the same, explaining that, “Vocabulary, grammar and most importantly, story, these are primary on my check list. The number of titles and genre are not as important. I would rather look for good scripts.”

Hossain acknowledges, there are those who rush to bring out books only at this time of the year instead of holding a book launch anytime during the rest of the year. “This one-month publishing is temporary, these books subsequently cannot be found in the market or in libraries,” he says. “They are actually not publishers, they are basically printers.”

The Boi Mela is set to have 550 stalls this year, up from 460 in 2018. Sales were estimated by the Bangla Academy to be around BDT 70 crore last year. While the figures seem impressive, they actually point towards a culture of book publication that seems to prize numbers over content. With so many books being published singularly for the month of February, in a rush to catch the mass audience gathered at the fair, one wonders how much attention is given to appraising the value of manuscripts and maintaining the standard of the printed product.

Many of the publishers we spoke to lament the lack of quality writing and the ebb of reading culture among the masses. But the way a book is introduced, and the way its pages and its formatting look and feel to a new reader affect their interest in buying it. Perhaps this void between readers and the literature being produced could be bridged if more publishers paid attention to truly developing a book from conception to production to marketing, instead of simply churning out titles for the annual festival. As Mahrukh Mohiuddin points out, “There are so many books at the fair, but the content and the production are lacking. It is important that there is better understanding of what we are offering readers. If I just compile something and put a shiny cover on it, is it a book?”

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments