Mapping Our Many Mother Tongues

Very recently, a video song called "Poran Priyo" released by the telecom provider Robi, featuring an all-girls band F Minor has been making the rounds on social media as a "pahari" song, but very few know that the language of the lyrics is actually Achik, the language of the Garo community. The language was not identified by the telecom, and the blanket labelling of the song as "pahari" erases the difference in identities of the multitudes of indigenous groups and ethnic communities living across the hilly regions. The hills in the north are very different from those in the south, and so are its people.

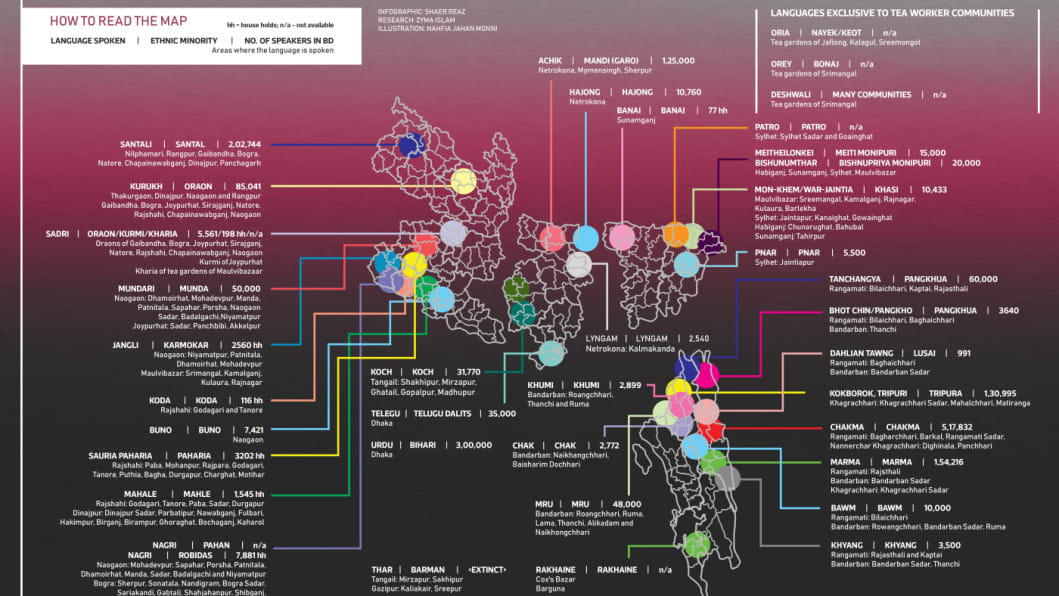

When it comes to languages other than Bangla, mainstream imagination extends as far as those spoken by more visible indigenous communities like Chakma and Marma, while policy discourse goes just a bit further to include the Santal, Tripura and Mandi (Garo). Even a language as prolifically spoken—and practiced—as Achik is overlooked in the face of majoritarian homogeneity, and tiny communities like the Lyngam of Kalmakanda upazila of Netrokona are basically invisible. It is easy enough to forget that in the Land of the Bangalees, there are at least 41 languages.

As we commemorate the struggle that gave us our hard-won mother-tongue, it is imperative to remember that the treasure-trove of languages spoken in this land are also facing struggles of their own—to be passed down to the next generation, to be practiced in literature, to be celebrated in songs. While some languages are still spoken by large vibrant communities on a daily basis, others are down to their last generation.

When trying to map out the languages spoken in this country, we realised there has not been a single extensive national survey that looks at all the ethnic communities and indigenous groups together. What this means is that there is no reliable statistic of the number of speakers of each of the languages of these communities. This is a very important statistic to have, seeing that many of them are going extinct. To compile all the information in the map, we had to refer to a variety of sources and surveys, including but not limited to, Survival on the Fringe: Adivasis of Bangladesh, Slaves in These Times: Tea Communities of Bangladesh and Lower Depths: Little-Known Ethnic Communities of Bangladesh published by Society for Environment and Human Development in 2011 and 2016 respectively, Indigenous Communities published by Asiatic Society of Bangladesh in 2007, Atlas of the Languages and Ethnic Communities of Chittagong Hill Tracts published by UNESCO in 2004, and Small Ethnic Groups in Bangladesh: A Mapping Exercise written by Mohammed Rafi and published by Panjeree Publications in 2004.

We acknowledge that one of the limitations of the map is that the data presented is dated—but this only reiterates the need for a timely survey to properly assess the current situation. Another limitation of the map is our inability to demarcate fully all the places where a certain community might live—we had to limit ourselves to the places where the population was the highest for that particular community.

We were also unable to find complete information about the languages spoken by over 280 ethnic communities working in the tea gardens in Sylhet due to the lack of a holistic survey. The languages spoken by the communities living across 159 tea gardens are Sadri, Santali, Oria, Monipuri, Telegu, Bangla, Deshwali and Mandi. They also speak a language known to the communities as "Jangli" or "Bagani bhasha" which is described by experts as an amalgamation of the many different languages spoken inside the tea gardens. The language serves as an efficient tool that grew out of the need to communicate between the many ethnic backgrounds of the tea workers.

This map also does not give a sense of exactly how at risk some of these languages are. One example is Koch or Thare Bhasha, which is a Tibeto-Burman language. Experts surveying the community report that members of the indigenous group, consisting of nearly 31,770 members, are fast switching to Bangla for their every day use. The language also does not have a written alphabet, which means its existence solely depends on it being passed down the generations.

Another group that has pretty overwhelmingly switched to speaking Bangla is the Konda, who live in the tea gardens of Maulvibazaar. Experts report that the group has its own separate language but that is now only known to the older generation. Bonaj is another ethnic group of the tea gardens of Srimangal, whose language Orey is only spoken by those of the older generation. The Rajbongshi community also have their own language but it is now fast being taken over by the comparatively more popular Deshwali, which is spoken by a larger number of people. All that is documented of the Rajbongshi (which does not even have an official documented name) are some words in the book by Asiatic Society: "diya" means riverbank, "normasin" means cloud and "nuti" means ant. The Halam of the tea gardens of Sylhet and Habiganj have also switched to Bangla, from Kokborok, which used to be their mother-tongue.

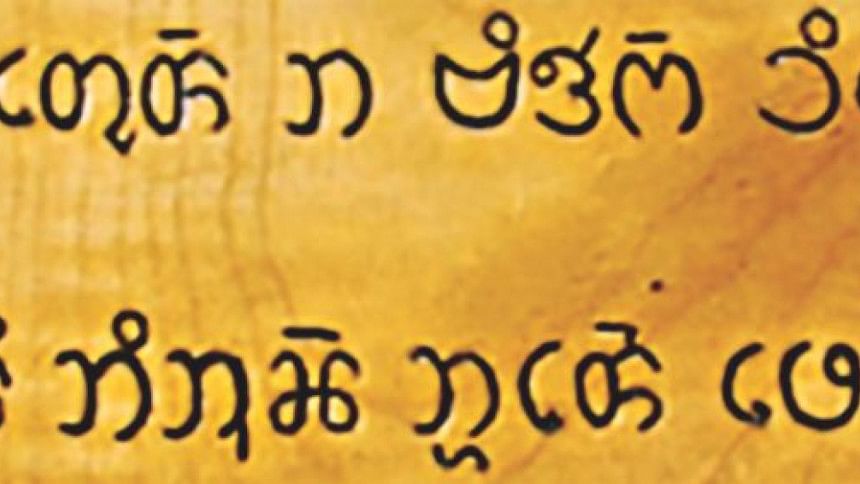

Outside of the tea gardens, another language that philologists report to be on the verge of extinction (in Bangladesh) is Nagri. The language is spoken by the Robidas—a community of 7,881 households in Bogra and Naogaon, and the Pahan community, who live in the same districts but whose population is unknown. While a variation of the language is enjoying a renaissance in the form of the resurgence of the Siloti-Nagri script, the vernacular language spoken by these ethnic communities is at risk of being lost. Unless these languages are documented soon, they will forever be lost in the annals of time.

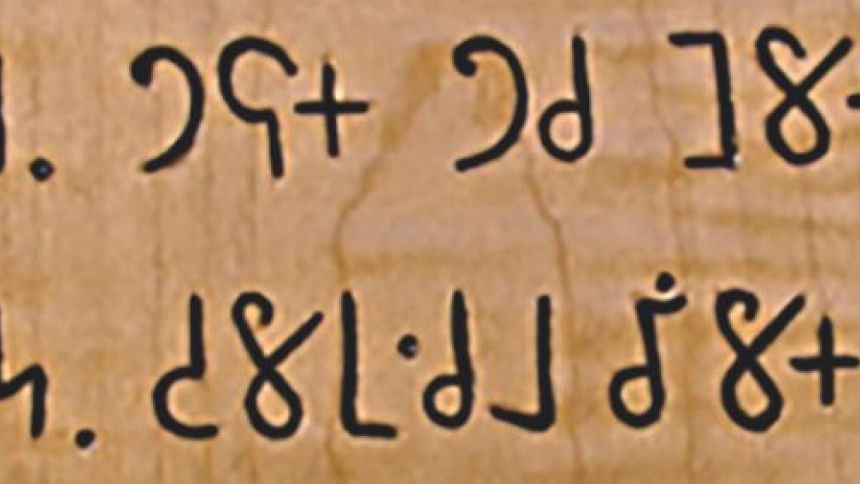

Most of the languages mentioned in the map do not have a written script, being originally vernacular only. Failure to document the phonology means that if the language does not perpetuate down generations, they will be lost. The Mro community developed a script as late as the 1980s to save their language from extinction. Some like Telegu, spoken by the Telugu Dalit community, do not exist out of the vernacular, not because the language does not have a written script, but because the community itself suffers from low literacy levels.

One fascinating fact about the many languages spoken in this small piece of land is that they are not of the same linguistic family. Bangla and Chakma are actually from the same linguistic group (Indo-Aryan), while Chakma and Marma are not, since the latter stems from the Tibeto-Burman range. While the map indicates which larger linguistic group each of the languages belong to, it could not get into the nitty-gritty. For example, Meitheilonkei (spoken by the Meitei Manipuri) is actually in the same linguistic subgroup called Kuki-Chin, as Bawm, Dahlian Tawng (spoken by the Lushai), Pangkho, Khyang and Khumi even though the Manipuri community is to the north, while the rest are from the south.

Just as interesting is the fact that several ethnic groups who identify as separate ethnic communities from Bangalis speak Bangla as a mother tongue. The Kshatriya are a very good example of this. A community of 1,22,098 households living in Panchagarh and Dinajpur, the community say they migrated from the Kshatriya kingdom of India, and thus are separate from Bangalis, but consider Bangla as a mother tongue.

Comments