Why are our major rivers no longer within humanity’s safe limits?

Globally, Bangladesh is known as the land of rivers and flooding. However, the transboundary nature of rivers in Bangladesh imposes a risk to water security, which is exacerbated by global climate change and anthropogenic activities such as urbanisation, booming agriculture, economic development, and population growth.

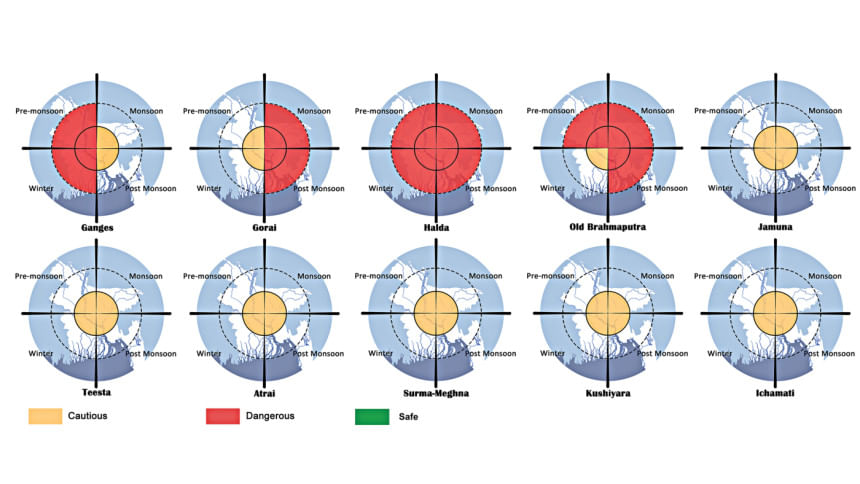

Four out of ten rivers in the Bangladesh delta – the Ganges (dry season), Gorai, Halda, and Old Brahmaputra – have surpassed the safe operating space, while the remaining six are classified as being in a cautious state due to hydrological alterations and minimum river flow requirements. This finding comes from our new study to define a safe operating space for major rivers in the Bangladesh delta, jointly led by the University of Glasgow and Bangladesh University of Professionals, in collaboration with Gazipur Agricultural University and Riverine People, and recently published in the journal Environmental Research Letters.

The concept of a safe operating space, first introduced in 2009 by Rockström and colleagues, assesses the overall health of the Earth by defining boundaries for critical systems – including climate, water, and biodiversity – beyond which conditions become dangerous for humanity. In 2023, Richardson and her team updated this framework, reporting that six of the nine planetary boundaries have already been crossed, among them freshwater, which is essential for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in the face of climate change.

The findings of our study also show that all seasonal river flows display a decreasing trend in the last three decades, except in the winter season, and that the majority of river flows have been altered (high to severe) in the Bangladesh delta. Our analysis highlights the challenges in maintaining a safe operating space for the Ganges River, despite the signing of the Ganges Water Sharing Treaty in 1996, which is set to expire in 2026.

Can one of the world's most climate-vulnerable deltas build resilience to climate change without securing a safe operating space for its rivers? This is a question that demands urgent attention, for the rivers of Bangladesh have shaped its economy, environment, and culture since the dawn of civilisation, sustaining agriculture, fisheries, mangroves, wetlands, and much more in the Bangladesh delta.

The several hydrological alterations and the dangerous state of rivers are mainly due to anthropogenic drivers such as reservoir construction, booming agriculture, economic development, conflicts in political regimes, and dam building. The impacts of these transgressed safe operating spaces and hydrological alterations in Bangladeshi rivers are already evidenced and well documented in scientific literature.

Fish species, including the most popular and national fish, hilsa, have, for example, become extinct in the upper reaches of the Ganges River basin. Many aquatic ecosystems and fish habitats, such as those in the Halda River, have been severely affected by low river water flow.

Although the increasing salinisation in coastal Bangladesh is known to be driven by sea level rise in response to global climate change, river flows are highly critical in maintaining the saline and freshwater balance due to the geophysical characteristics of Bangladesh. The reduction of river flow has already resulted in elevated salinity, which has adversely affected the world's largest mangrove forest, the Sundarbans, agricultural production, and social-ecological systems in the coastal and other regions of the Bangladesh delta. Due to excessive upstream water extraction, substantial increases in salinity levels in the Gorai River have adversely affected fisheries, agricultural yields, and the population of freshwater dolphins in the Ganges. All these consequences are particularly alarming as the Ganges treaty between India and Bangladesh is set to expire in 2026.

Can Bangladesh champion transboundary water conflict resolution?

Though the dangerous state of major rivers can directly hit hard the 170 million population in Bangladesh, there are also transboundary consequences of the river water crisis. The recent water conflict between India and Pakistan, and China's plans for a new dam on the Brahmaputra, highlight that South Asia is one of the hotspots of water conflicts, which can be triggered by climate change and human-made interventions in transboundary rivers.

The destruction of the world's largest mangrove forest due to low river water flow, and increasing salinisation (indirectly accelerated by low river flow), could negatively disrupt the regional climate system in Bangladesh, including India and Nepal. Ultimately, transboundary water insecurity and conflicts could jeopardise South Asia's goals of poverty eradication and ensuring no one is left behind. Therefore, a holistic social-ecological systems approach is required to ensure water security and enhance resilience to climate change in South Asian countries.

However, the solution to this problem is not a simple task, as it requires transboundary and international support and cooperation to ensure fair and equitable treaties, ecological restoration, and technological solutions to maintain the river flow within the safe operating space in the Bangladesh delta. This is particularly challenging due to transboundary rivers that drain many countries such as China, India, Nepal, and Pakistan. Often these countries' political regimes are not in a state for transboundary negotiation to resolve the conflict of sharing water, which requires meeting the basic human needs of nearly 700 million people.

Success stories such as the Mekong River Commission (e.g. mutual benefit, sharing accurate and appropriate technical information) and the Indus Waters Treaty (e.g. multi-tiered dispute resolution process) could be adopted for bilateral and multilateral treaties with India, including Nepal for the Ganges, and China and Bhutan for the Jamuna River, respectively.

There are some critical perspectives to examine before negotiating the share of transboundary rivers. For example, while the 1996 Ganges Treaty was a diplomatic breakthrough given the geopolitics of water, our analysis reveals a complex reality. Although the Padma River's flow remained relatively stable from 2000 to 2018, it was substantially lower than pre-1976 levels, before the Farakka Dam's construction in India.

The impacts of the Farakka Dam are clearly evident both in India and Bangladesh. Furthermore, according to The Hindustan Times and The Economic Times, nearly 1,000 dams built across the Ganges River basin in India have significantly altered, restricted, and diverted river water flow. Therefore, the diversion of river water flow through dams in a river basin also needs to be accounted for when negotiating water share from a holistic systems perspective.

Our political leaders must urgently prioritise water sharing and climate change as a stable political agenda, ensuring these targets remain consistent despite changes in national or transboundary political regimes. We need trained people who understand and are equipped with interdisciplinary knowledge and skills in water and climate change, regardless of their political identity. Crucially, transboundary water disputes must be resolved inclusively and collaboratively with all countries, ensuring no nation is excluded. Bangladesh should bring the excluded transboundary rivers back into the discussion. Our classrooms need to be turned into places for critical thinking and active learning engagement to train future leaders on water, climate, and sustainability.

Bangladesh needs stocktaking studies of the transboundary rivers as well. Though the Joint River Commission officially listed 54 transboundary rivers between Bangladesh and India, the number is far higher. According to a 2021 study by Riverine People, a civil society organisation, there are at least 126 transboundary rivers between Bangladesh and India. Bangladesh's foreign ministry proposed 16 more transboundary rivers to be included in the official list in 2016, but its Indian counterpart has not yet responded.

In addition to negotiation, treaties, and political will for resolving transboundary water disputes, ecological restoration—such as reducing deforestation, managing changes in land use, and restoring wetlands and canals—may enhance resilience to flooding and water security in the Bangladesh delta. The water storage capacity must be improved by regenerating canals and adopting nature-based solutions such as ponds, and spaces for storing water to manage heavy rainfall and sudden upstream river flows.

Cutting-edge technologies such as Artificial Intelligence can help prevent severe damage to livelihoods due to flash floods. Remote sensing provides real-time, basin-wide monitoring of river flow, sediment, and ecological changes, offering data-driven, transparent, and unbiased information for transboundary negotiations. Integrating satellite observations with hydrological models supports equitable water sharing and early warning for climate resilience.

Importantly, the future water treaties for sharing transboundary water must be based on historical river flow, independent of existing infrastructure, and projections of climate change. Adopting tax-based water sharing can be a novel approach for sharing water among the countries sharing the river basin. Countries using more water would pay more tax, and the revenue would be redistributed among the other countries that share rivers in the treaty.

Dr Md Sarwar Hossain, Associate Professor and Programme Director of MSc in Environmental Risk Management, School of Social & Environmental Sustainability, University of Glasgow.

Alamgir Kabir, Assistant Professor, Department of Environmental Science, Bangladesh University of Professionals

Md Mahmudul Hasan, Department of Environmental Science, Bangladesh University of Professionals

Sheikh Rokonuzzaman, Riverine People

Hasan Muhammad Abdullah, Associate Professor, Department of Agroforestry and Environment, Gazipur Agricultural University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments