My Nana Jaan, Poet Abul Hussain

My grandfather was like a banyan tree, majestic and inspiring in many ways.

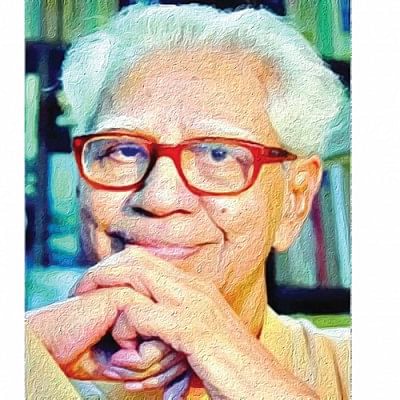

At 5 feet 11, he towered physically over many, stooping slightly burdened by age in his later years. His quiet demeanour and slow determined gait belied a steely grit that was evident to those who knew him. His buttercream skin was speckled with reddish freckles that stood out like tiny stars. His gunmetal silver hair brushed back over his crown like a waterfall, never out of place.

My Nana Jaan was Abul Hussain, the first modern Bengali poet in Bangladesh and the author of more than 30 poetry and prose books, winner of the Ekushey Padak and numerous other awards and accolades. I was his Nanu Moni.

My earliest memories of Nana Jaan are of him sitting in the library of his two-storied Dhanmondi house, hunched over a grand wooden desk, scribbling in a notebook, surrounded by the smoky, earthy scent of books. I played in one corner of the room not knowing I was in the presence of an extraordinary man.

Even at a young age, I sensed I should not disturb him when he rested the pen on his lip ever so lightly from time to time, as he paused (I assume) to think of a word or a phrase. How does one sit in silence for so long? Silence was his best friend.

He was quiet and unassuming, but never intimidating. He seldom spoke, but when he did, he spoke eloquently. I never heard him raise his voice, even when upset or angry.

Nana Jaan came from a distinguished family. His father was a senior officer in the police department, and his brother, a Supreme Court lawyer and minister in the government. He himself was a senior government official, who travelled the world for work and lived in Thailand for a number of years. My mother and her siblings, barring the eldest, were all born there.

He never had to struggle in life, but I understood from my mother that his real struggle was between living a life doing what he loved (writing) and making a living (holding a government job).

Poetry is what filled him with happiness and joy. His other life that of a civil servant, was mundane in comparison.

He led the life of a simple man, preferring simple trousers and shirts, crisply ironed. He avoided rich food, eating simply cooked rice or chapatis, lentils, fish and vegetables, day in and day out. He would go for a two-hour morning walk every day until old age made it impossible. Little did I know this was due to living with diabetes for four decades. He was so disciplined, he never succumbed to the temptations of sugary treats and desserts and never deviated from his routine.

He was similarly measured in his emotions. He refused to wear his emotions on his sleeves, remaining resolute and calm in the face of adversity and heartbreak.

When his father was executed by the Pakistani army during the Liberation War in 1971, he locked himself in his study, not coming out for days. No sound came from the room, no screaming or crying was heard, no pounding of fists. Just silence. When his daughter died a few days after birth, he told my Nani, "The Almighty has taken what belongs to Him. It is not for us to ask why."

Not that he was emotionally deficient, he just did not like drama, or rather he did not allow emotions to take over. He felt one could see things more clearly and from different perspectives when not overwhelmed by emotions. His poetry reflected this side of his personality. He wrote about the ordinary lives of ordinary people and the extraordinary lives of extraordinary people in conversational language, never augmenting their lives or using poetic diction.

Nana Jaan was a private man. He did not need validation from others, nor did he care about feeding his ego. I often saw him shooing away reporters who wanted to interview him, even as they returned without fail. It was both amusing and surprising to me.

He believed all men and women were born equal and died equal. The day he passed away, many people came to pay their respects. He had two funerals. I don't think he would have liked it.

Bury me in an unmarked pauper's grave. Remember me as an ordinary man, he said.

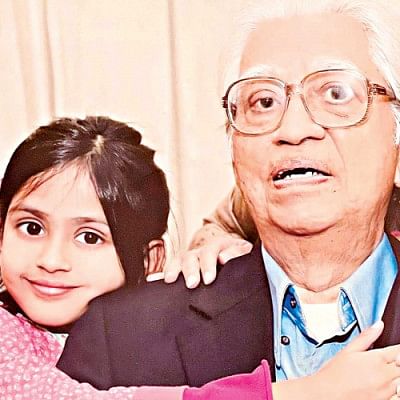

To his grandchildren, he was sweet and non-preachy. He was an indulgent grandfather, as grandparents across the world are, allowing us to be naughty, giving us sweet knowing smiles when we were up to no good. He clearly relished our presence and it broke his heart that his wife wasn't alive to see her grandchildren; she passed away in 1994.

Nana Jaan named the first of his grandchildren after his wife. He wrote many poems about, or for us. A whole book of children's poems, Shahaner Boi, is dedicated to the oldest among us. The poem Dui Bon (published in Kobita Shomogro)is about the youngest of the lot.

It has been seven years since Nana Jaan left us on June 29, 2014. His calm and loving presence remains in our lives, in our memories, pictures and books. I hope he will live on forever in the hearts of poetry loving Bengalis.

The writer is a high school student in Washington, D.C.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments