Unpacking the proposed reforms to our revenue system

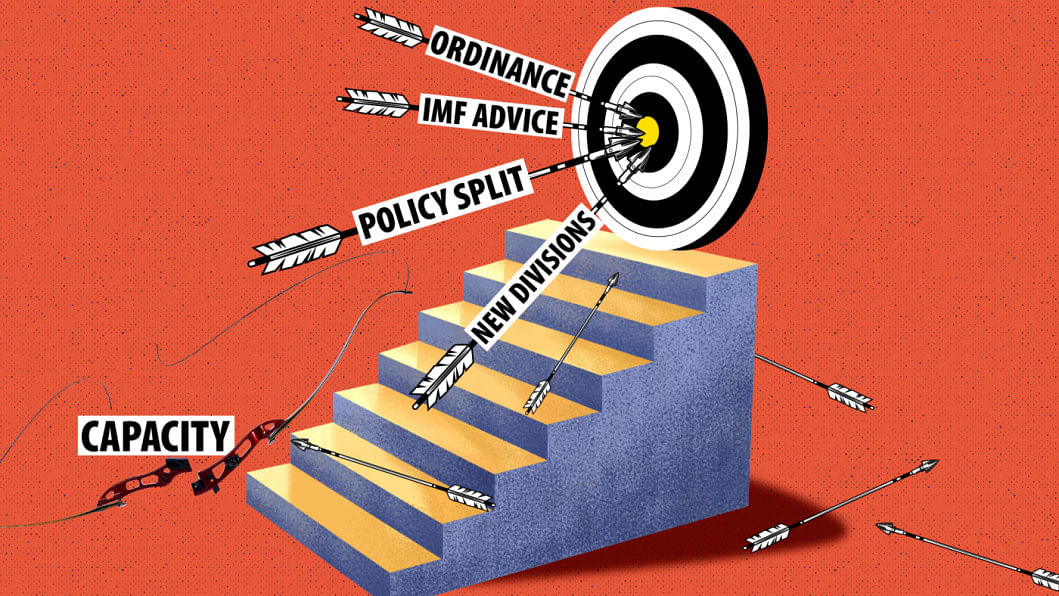

The low tax-GDP ratio of Bangladesh has often been attributed both to the weakness of the tax administration and to the lack of innovation and reform in the tax system. Successive administrations have set lofty revenue collection targets without undertaking meaningful reforms and have remained oblivious to capacity concerns. The large annual shortfalls (e.g., typically about 14-15 percent) in realised revenue over target have hardly been a surprise.

The interim government (IG) has just passed an ordinance dissolving the erstwhile National Board of Revenue (NBR) and has created two new bodies, namely the Revenue Policy Division (RPD) and the Revenue Management Division (RMD), under the direct oversight of the Ministry of Finance (MoF). This has been done in the anticipation that separating the revenue policy-setting process from that of tax collection would permit the RMD to devote more energy to tax administration. Indeed, this view has been promoted by multilateral agencies, especially the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Promulgation of the ordinance was preceded by the MoF launching an Advisory Committee to investigate the subject, which duly submitted its recommendations some months ago.

Two salient points are in order. First, a separation of policymaking from that of tax administration is standard practice in most modern revenue systems. In Canada, the Canada Revenue Agency is in charge of tax collection. It even reports to a separate minister of national revenue, not finance. Secondly, merely splitting the tasks by itself, IMF notwithstanding, will not breathe new life into the stagnant tax-GDP ratio. That would require both significant tax reforms as well as augmenting tax administration capacity.

The primary logic behind the separation of revenue tasks at issue is to inject an element of operational independence into the proposed bodies. Revenue administration regimes in OECD countries operate as independent entities, albeit working within the broader framework of public accountability. Creating a division within the MoF is not a step in the right direction. Worse, the draft ordinance proposes that the RPD will be entrusted with the task of monitoring the application of tax laws as well as revenue collection undertaken by the RMD (Section 5, Clause 6, "cha"). The latter implies a hierarchical pattern between the two divisions, contrary to the spirit of their separation. This is a no-go. Several members of the MoF Advisory Committee have spoken out, arguing that the ordinance grossly misrepresents their recommendations; the committee's vision was to create an autonomous entity outside the direct control of any ministry.

Beyond the principle outlined above, the proposed ordinance points to a misconception of how to improve the efficacy of the revenue administration process. With an unchanged tax code, the tax-GDP ratio can be enhanced only if the administrative body can expend greater effort, benefit from additional training, and adopt suitable technology. To that end, it will be necessary to bring about innovation whereby suitable candidates can be recruited, promoted, and retained through timely performance reviews, thereby upgrading the overall tax administration capacity on a sustained basis. That goal would require a compensation structure commensurate with safeguarding high professionalism in the cadres and weeding out endemic corruption. The statutes posed in the proposed ordinance are at odds with these objectives. To boost staff morale, one needs transparency in the staffing modalities in terms of experience and qualifications required, especially at the upper echelons. This aspect has already caused dissension among the ranks, who have reportedly called for revoking the ordinance altogether, citing, among other things, the absence of due prior consultation with the primary stakeholders, the NBR staff.

When it comes to tax policy design, the new body can be made more effective by injecting an element of operational independence. After all, this body would serve as an adviser to the MoF. Should the minister find the recommendations agreeable, he/she must in turn propose these as laws to be placed before parliament for due deliberation and decision. One way of envisioning its modus operandi would be that the minister tasks the body to, say, find viable means of doubling the existing tax-GDP ratio within a certain timeframe, whereby the bulk of the revenue will be made up of direct taxes and VAT, but by gradually lessening the taxation of imports beyond VAT, namely tariffs. Obviously, the minister may also, as is pertinent, make less grandiose demands. Alternatively, the policy body may, of its own volition, examine the feasibility of a certain tax-revenue reform. Whatever the task—directed from above or arising from within—the revenue policy entity must have administrative freedom and adequate resources (including suitable staffing) to do its job without hindrance. The design of tax reforms is inherently difficult, often requiring substantial input from advisers from academia, the legal and/or the business community. These processes require independence rather than interference from the higher administration.

Furthermore, it is the revenue administration body that needs to be insulated from political pressure in conducting its routine work, namely, to implement the tax/revenue laws of the nation without fear or favour. On the issue of capacity, the recruitment process of taxation/excise/tariff staff should be separated from that of general administration, somewhat along the lines of the Bangladesh Bank. The logic is that the background preparation for the former would be more specific.

The new ordinance also entails anomalies in dealing with appeals. On one hand, in Section 4 (Clause 5) it calls for attaching the Appeal Tribunals for income tax, excise and VAT to the Revenue Policy Division. At the same time, in describing the scope of the Revenue Management Division (Section 7, Clause 9), it suggests the opposite. The principled point is that most appeals concern the application of tax laws, and not a contest of the law itself, and hence the responsibility of expeditiously dealing with such appeals ought to be part and parcel of revenue administration.

The separation of policy-setting from that of revenue administration is welcome. Ideally, both entities ought to enjoy full operational independence in fulfilling their mandates, though the case is stronger for the tax administration entity. Hence, creating two divisions within the MoF is not the way to safeguard this objective. The two entities should be renamed to better fit their mandates—namely i) Bangladesh Revenue Authority; and ii) Bangladesh Revenue Policy Institute. In view of the presumed responsibility, each entity should be headed by a minister of state, especially the former. In terms of the allocation of staff, the existing NBR personnel should be invited to indicate a preference to work in one of the two bodies, with a one-line explanation in support of their choice. The Internal Resources Division (MoF) staff may likewise be asked for their preference to join the new policy entity or be absorbed into the general administration. And the process of staff allocation can be reviewed by an expert body made up of both internal and external members.

Syed M. Ahsan, PhD is professor emeritus of Economics at Concordia University in Montreal, Canada.

Views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Follow The Daily Star Opinion on Facebook for the latest opinions, commentaries and analyses by experts and professionals. To contribute your article or letter to The Daily Star Opinion, see our guidelines for submission.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments