My father was an undocumented migrant worker. People like him don’t deserve your scorn

Not long ago, I was watching a webinar on the plight of returning migrant workers streamed live on Facebook by The Daily Star. One of the speakers, a top official at the ministry of expatriates' welfare and overseas employment, after outlining the government's initiatives in this regard in exhaustive detail, asked her audience: "Why are there so many illegal Bangladeshi migrant workers? When workers from other countries have passports and valid papers, why do Bangladeshis have to hear that they are illegal and undocumented?" We should think about it, she said, hinting at the practice of migrants going abroad through irregular channels.

I'm no expert on labour migration but there is usually a classist subtext to such questions, an unspoken rebuke directed at the poor migrants for their own misfortunes. Woven into this train of thought is the idea that their "ways" are essentially flawed and their lack of legal status is as much a problem for them as it is for the image of the country. Of particular note is the use of the word "illegal". Just as in the remarks of the said official, you see this word being carelessly bandied about in public discourses and media outlets, even though the world has long decided that illegal migrants do not exist—because no human being is illegal. Our insistence on using this dehumanising term denies their innate dignity and disregards the multiple factors that may be responsible for their condition. It also places them on a pedestal below other migrant workers. So the question that should be really asked is: how much of this is of their own making?

I don't presume to speak for all undocumented workers but I can share what I know from personal experience, with the hope that it will add to the existing discourse on labour migration.

I come from a lower-middle-class family of migrant workers. Until recently, overseas migration was in our DNA. The desire to change their fortune led many male members of our extended family to seek work opportunities abroad. I grew up hearing tales of their career progression: a certain fupa was doing well at his maintenance job in a Kuwaiti airport, a certain khalu rose through the ranks at an engineering consulting firm in Abu Dhabi, a certain uncle worked as a supervisor at a construction company in Singapore. There were also the tales of failed bids and ruined careers: a certain cousin was languishing in a Saudi neighbourhood without a job, the husband of another cousin was forced to come back from Kuwait. My own father belonged to the second category, and it was he who gave me the first real insight into the life of an undocumented migrant worker.

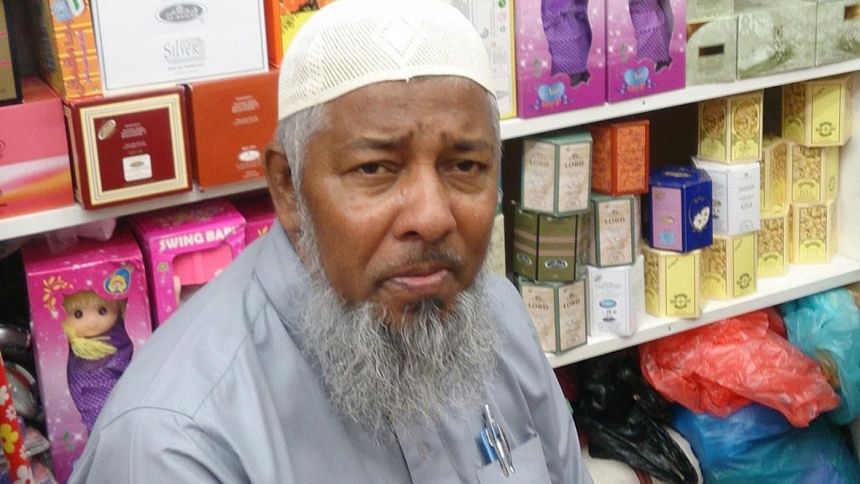

My father left us to work in Riyadh in 1998. Before then, he had a small company that manufactured tin buckets, trunks and so on. It was a time when many traditional jobs and businesses in Dhaka and elsewhere were in the process of being extinct. Unable to evolve in a changing market, he managed a "free visa" and flew to Saudi Arabia, leaving behind three children and his wife who was then pregnant with their fourth child.

None of us knew then that he wouldn't be able to return to his country until after 19 years, in 2017.

It still feels unreal when I think how he lived without us—and we without him—all these years. While he was away, his children, including his then-unborn daughter, grew into adults; his older daughter married and had children of her own; his mother, of whom he was so fond, died, as did many friends and relatives; his wife turned into an old woman; his village home, where he always wanted to go back and settle down, fell into disrepair; and his country changed forever. Trapped in a foreign land, he saw the most defining moments of his life pass him by like they were not his own, like he was watching them in some surrealist TV show on the meaninglessness of life.

For the most part of his stay in Saudi Arabia, my father had been undocumented and he couldn't come back without risking incarceration or plunging his family into further financial hardship. It wasn't so bad initially, though. In Riyadh, where his odyssey began, he had his iqama (residence permit) with him and made a decent start with the assistance of my mama, who got him a job in an aluminium workshop. After seven months, he quit the job to open a fruits and vegetables shop. Within a month, however, his plan suffered a blow as the government issued a decree banning the fruits and vegetables business for foreigners. So he turned it into a stationery shop. After about a year, the government issued another decree banning foreigners from running shops smaller than 40 square metres. My father's was 36 square metres.

This time he had no choice but to sell the shop along with all the merchandise. He found a prospective buyer and went to his kafeel (sponsor) to get his approval for the transfer of ownership. The latter assured him of cooperation but secretly sold the shop himself (he was its owner on paper), swindling my father out of his money. Meanwhile, he suffered another blow when two visas that he had purchased on behalf of an uncle and a cousin were found to be duplicate. Every decision he made seemed to be coming back to haunt him. Then with the help of a son of the kafeel, after about three years since his flight to Riyadh, he got his passport back and travelled to Mecca with a demand letter acquired from another kafeel, who promised to give him a valid work permit.

In Mecca, there was no change in his luck either, as this second kafeel misspent the fees he paid for his work permit and transfer papers. So he had to pay again for these papers. He was also heavily in debt by then. For the remainder of his time in Mecca, he would have to make do with a supervisor job at a motel for Hajis.

About a year later, he found a way to get transferred to Medina under another kafeel and started selling burqas to shops. It was a hassle-free business. For the next four years, he worked with legal permits. In his fifth year in Medina, trouble emerged again after it was discovered that his kafeel had been dodging taxes due for having foreign hires. He surrendered their passports to the government, claiming his recruits had all fled away. As a result, not only did my father and others like him fail to renew their work permits or get transferred under another kafeel, they also became fugitives under the law. Through no fault of his own, he became undocumented again, and would have to stay under the radar to avoid detention.

Fast forward to 2013-2014, the Saudi government offered a deal for the undocumented workers to get legal again, provided they paid for work permits for all the years they had worked illegally. It was a big opportunity for my father even though the cost was high. He found a willing kafeel and paid him SR 20,000 to get the necessary papers and permits. But as luck would have it, he was duped again as the kafeel vanished with the money. There were several others he knew who also got duped. They all filed cases against the kafeel at the labour court, but nothing would come of it, and my father would go on to remain undocumented. Finally, in 2017, the government announced an amnesty for irregular migrants who could go back home without being imprisoned. Sick and decayed with old age, he gratefully accepted the offer.

My father is the longest-suffering migrant worker I know. But the way he suffered and got harassed by local kafeels is quite common. These stories of hardship and exploitation that we often come across are proof that migrants may become undocumented through no fault of their own. Central to their vulnerability is the exploitative kafala or "sponsorship" system in some Gulf countries. It's intrinsically connected with the "free visas" which, as should be clear from the account of my father, are not free in any monetary sense, but free of an employer or job. According to a white paper of the International Labour Organization (ILO) published in 2016, "the sponsor named on the visa does not actually employ the worker. Sometimes, fake companies are registered simply to obtain and sell free visas." Despite their being employers only on paper, these kafeels have a stranglehold on the workers as they hold their passports, putting them in a precarious legal position, and face hardly any consequence for their crimes and transgressions.

In hindsight, my father may have been guilty of not having an actual job when he left for Riyadh, but it's a guilt he shares with most migrants who are equally desperate to provide for their family but are exploited by local agents and recruitment agencies in their country as well as the shady companies and kafeels that control their fate in the destination countries. We need to dismantle this kafala system. We need to be more proactive in terms of putting the right policies and practices in place. And we need to stop blaming our irregular migrant workers for their misfortunes. The buck stops with the government—not the other way round.

Badiuzzaman Bay is a member of the editorial team at The Daily Star. Email: [email protected]

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments