Dr Muhammad Shahidullah: A tribute

Dr Shahidullah is one of the greatest linguists that the South Asian region has produced. This is a universally acknowledged fact and one can easily use it as the beginning statement of an article on him. This venerable scholar, whose bust photograph most often displayed a white beard and a fez on his head, was once branded as 'the Grand Old Man of Pakistani linguistics' (in the Shahidullah Presentation Volume, ed. by Anwar Shah Dil). But he never lent himself to become a bone of contention in South Asia, where countries changed their names and identities in the last century, some more than once. Three major ones, namely India, Pakistan and Bangladesh can claim him equally, as he was born (10 July 1885) in the undivided India, adopted the then East Pakistan as his domicile, and unfortunately did not live just another two years to find the birth of Bangladesh, which, I am sure, was a part of his dream for long.

His original home was the village of Peyara, in the then district of 24 Parganas, now North 24 Parganas, in the southernmost part of West Bengal. He comes from a traditionally religious family, following Sufi faith practices. He was the son of 'Munshi' Mafizuddin Ahmed and Marguba Khatun. His father was a warden, attached to the shrine of Pir Gorachand. His father's felicitous decision was for his son to have modern education has been a blessing for Bengali society and culture.

It seems that life had pre-ordained for Shahidullah that he would become a polyglot and a linguist. In his early years, he was exposed to Arabic, Persian and Urdu at home, and then in school, where Sanskrit was the only classical language available for study, he had to take it. And he began to love the language. So much so that he continued the study of Sanskrit in his Intermediate Arts (then called First Arts), and made it his major (Honours) course of study in his graduate years. Early in his school years, he says, "learning languages became an obsession with me. When other boys ordinarily passed their time flying kites, spinning tops and what not, I spent it learning languages." (Amar Sahitya Jiban). One may want to hazard a guess that the similarities (Persian and Sanskrit, for example) and contrasts (Arabic and Sanskrit) in the components and structures of languages he was learning may have intrigued him, and probably enhanced his thirst for delving deeper into this absolute human faculty. The theoretical framework at his time was historical and comparative linguistics, in which domain he would do important work later.

Poverty caused interruptions in his study after his First Arts (1906), and he finally graduated from City College, Calcutta, with reasonable grades in 1910. He was probably the first Indian Muslim student to carry the study of Sanskrit so far. And he was all set, and he had a right, to carry it further, that is, to take up Sanskrit in his M. A. course at the University of Calcutta, then the only University in the Bengali-speaking regions.

2

He faced an uncouth impediment to his plans, a Brahmin teacher (most Sanskritists then usually were) of the Vedas in the Department of Sanskrit named Pt. Satyabrata Samashramee, refused to approve the admission of a Muslim boy in that department of the University and threatened suicide by fasting if he were allowed to. People were stunned, but the University authorities, headed by the powerful Sir Asutosh Mukherjee, were helpless against such blackmailing. The newspaper, Bengalee, edited by Surendranath Banerjee (1848-1925) wrote that "the Pundits should be thrown into the Ganges". But the Brahmin was not to budge from his grim resolve. He would not teach the Vedas to a Muslim boy. One can add here that much later, a Bengali girl, this time a Christian, was not allowed to enter the classrooms of the same Department but had to sit in a chair outside its doors to listen to the lectures. Her name was Sukumari Bhattacharya, who later turned out to be a great Sanskrit scholar. One should also add that things have changed now. Now quite a few Muslim girls and boys study Sanskrit in the postgraduate classes in West Bengal universities, and one is not surprised if one of them tops in the examinations.

Sir Asutosh, who would offer help to Shahidullah on later occasions also, finally found a way out. He proposed to Shahidullah that he take admission at the new Department of Comparative Philology (est. 1904), which the latter did. And, considering everything, we think this is one of the best choices he made in his learning life. Comparative Philology, then a completely new discipline in India (the Department of the University was the first of its kind in Asia too), would open a much wider horizon to Shahidullah, and being tied down to Sanskrit alone would not suit his polyglot temperament. I am sure he had thoroughly revelled in the linguistic feast he was offered in his Department, and that created a new Shahidullah, much more welcome and beneficial to the academia than a mere Sanskrit scholar.

3

As it happened in a colonised country, excellent results in a somewhat esoteric discipline were no promise for a good and guaranteed career. He obtained a law degree along with his M. A. (1912), but that was not of much help either. He already had to break his graduate studies and take a teaching position in Jessore District School. Even after doing his M. A., his situation did not improve. A short stint as a manager in a Muslim orphanage, practice of law at Basirhat Court in his district—were listless attempts of finding a secure career. Meanwhile, he had to refuse a scholarship for higher studies in Germany as, some say, he could not get a medical clearance.

Sir Asutosh came to his rescue once again. He called back Shahidullah from law saying that, "Shahidullah, the bar is not your place, you must come back to the University.", and made him a research scholar at the Department of Bengali, at the University, to help the work of Dinesh Chandra Sen, then head of the Department. But it is said that an offer of an additional 50 rupees made him leave his alma mater to join the Bengali and Sanskrit Department of Dhaka (then Dacca) University, just established, in 1921. That determined the location where his ultimate refuge and place of work was going to be. Calcutta's loss was, undoubtedly, a huge gain for Dhaka.

4

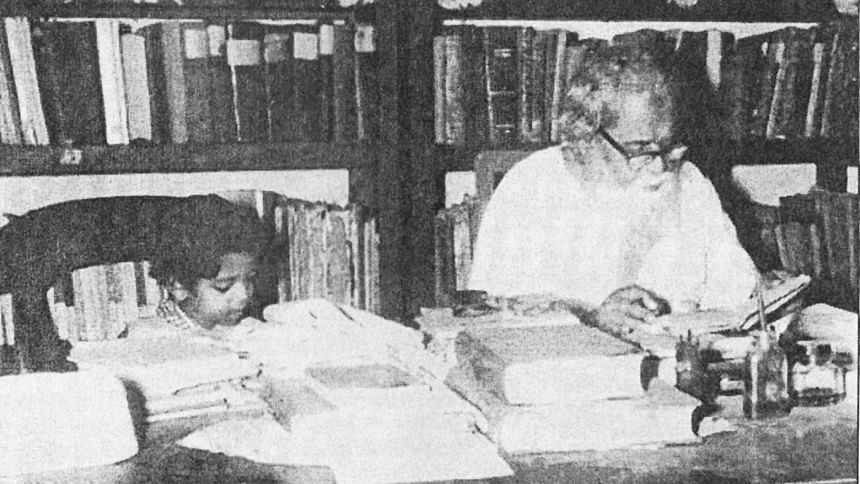

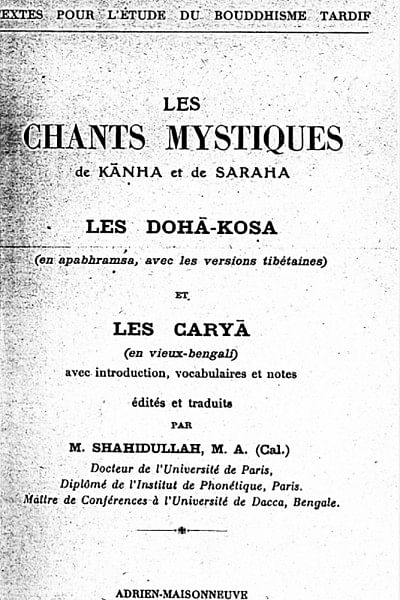

In Dhaka, Shahidullah seems to have found the security and opportunities to expand his activities and interests in many directions. But let us cover his linguistic work first. It has already been noted that Shahidullah, like Suniti Kumar Chatterjee (1890-1977), his junior in the Department, had to work within the framework of Comparative and Historical Linguistics--'Philology' in short. Here his major work was 'Outlines of an Historical Grammar of the Bengali Language', which was published a year before S. K. Chatterjee's more voluminous work, The Origin and the Development of the Bengali Languages (1926). In it, Shahidullah's original contribution was the emphasis he laid on the non-Aryan connections of Bangla language. He has also done pioneering research in Phonetics of Bangla, at the University of Paris in 1928, for which he received the 'Diplome de Phonetique experimentale'. His Paris stays also fetched him a doctorate of Sorbonne University, for his study of the dialect of the Charya songs. His articles on Ramasharman's Apabhramsa verse, linguistic features of the Asokan edicts, Mundari and Bangla, Aryanization of Ceylone, origins of Bangla and Ceylonese, the language of Pashto, Sumerian language and Urdu and a hundred others, including the dialect of the district he was born, south 24 Parganas. One is amazed at the range of his interests and investigation, but also at his quite original statements about the topics chosen.

A reputed Bengali scholar, Haraprashad Shastri (1853-1931) was then the Head of the Bengali-Sanskrit Department at the University of Dacca, and his association stimulated Shahidullah in widening his focus. Archaeology and folklore were brought into his ever-widening orbit. On the one hand, he wrote articles like 'The Gita and the Truth About Shrikrishna', 'Bharata, Kanva and Vishwamitra', 'A Different Version of the Shrimadbhagabadgita etc., while on the other, he went all out to collect folklore of East Bengal, where one of its richest repositories in the world could be found, by founding a 'Lokasahitya Samgraha Samiti' at the Department. The Samiti began collecting items of folklore from different parts of East Bengal, supported by a 'scanty' allowance from the University. I am sure that the rich collection of tales, proverbs, ballads, oral history etc. that have been published in East Bengal during the early Pakistan period, came doubtlessly from the impetus provided by Shahidullah. Suniti Kumar Chatterjee evaluates the contribution of his senior thus: "I have always appreciated his 'scientific' [temperament], that is well-reasoned judgement in his discussion of literature and linguistics. He has brought new insights in our common areas of interest, phonetics and philology, some of which I have gladly accepted, some I could not." Shahidullah's most valuable contribution was, according to Chatterjee, "Significant deliberations on Bengal's language and culture, and, in addition, ascertaining the contribution of Muslim Bengalis."

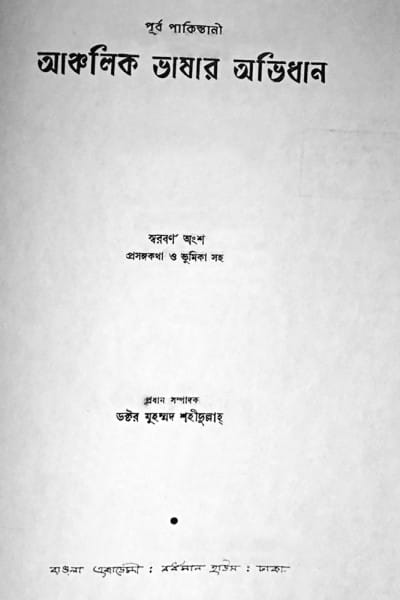

Many big academic projects were undertaken under his guidance. In 1949, the new Government of East Pakistan instituted an East Pakistan Language Committee, professedly to 'modernise' Bangla, with Maulana Akram Khan as the chairman. Dr Shahidullah, as its most important member, created a Shoja Bangla orthography, which, however scientific in its approach (the writing system was made linear), was not accepted in popular practice. Was it considered as an imposition by the West Pakistani authorities--we do not exactly know, but the recommendations passed into oblivion almost silently. He was called to Karachi to edit a comprehensive Urdu dictionary, and an Islamic Encyclopedia was also initiated under his editorship. His lasting contribution in this area is Purba Pakistaner (now Bangladesher) Anchalik Bhashar Abhidhan, a two-volume dictionary of East Bengal dialects (1965), the like of which has yet to be attempted and witnessed in West Bengal. In the history of Bangla literature, he provided definite evidence that the Chandidas of Shrikrishnakirtan was a pre-Chaitanya poet.

And that was not all. This encyclopedic talent, who was fondly called Jnanatapas—a savant, eventually became the teacher of a whole nation. Teacher, guardian, and finally, the conscience of it, as it, uncertainly at first, moved towards independence. A devout Muslim himself, he was a non-communal and liberal soul, which is reflected in his sons' leaning towards communist ideology. He was for a Bengali identity beyond religious affiliations, as his article on the meeting points of Hinduism and Islam (Udbodhan, 1956) would show. And his address as the President of the Purba Pakistan Sahitya Sammelan in March, 1956 is memorable, "…It is a fact that we are Hindus and Muslims, but that we are Bengalis is a greater truth. I'm not saying this as an ideal, it is a reality. Mother nature has put such an imprint on our physique and our language that we can hardly conceal it with a garland, a tilak, and a tiki, or a cap, 'lungi' or beard." He did not ever forget his birthplace, his village in West Bengal and said, "Your mother remains the same even when you live in an alien land, so your birthplace ever remains your birthplace."

But he loved East Bengal, and took a leading part in directing its struggle against the cultural hegemony of West Pakistan. Although fond of the language of his religion, Arabic, he was a leading voice in the language movement, and vehemently opposed Urdu, not just as the state language of Pakistan, but also against the shaping of Bengali on religious lines. His sarcastic statement about some attempts of shaping the Bangla literary language along communal lines, (which was otherwise dubbed 'Pak-Bangla'), makes that amply clear, "Musalmani Bangla can surely be a spoken dialect like such others in East Bengal (he writes, 'Bangladesh'!), but that will not be our language of literature. You cannot direct a path for (flowing) water, it finds its own path. Mussalmans in Bengal have automatically decided on a language in which they will create literature. There may be some who want to change the mother tongue of the Bengali Mussalman into Urdu, by the mere force of the pen. I think their pen is made out of the bones of an ape." This he says in spite of his rumination that had the English lost in Plassey, the Bangla literary language would have been different.

We forget or remove our attention from such men and destabilise our own identity as Bengalis.

Pabitra Sarkar is an author and former vice-chancellor of Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments