The Liberation War Museum narrating collective trauma

Liberation War Museum (LWM) in Dhaka tells the story not only of the Liberation War but also of the long struggles of breaking the fetters that, over the decades, led to the ultimate formation of Bangladesh. For a nation that went through as many major tragedies as Bangladesh, this is not merely a museum meant for education or recreation but a site of personally meaningful memory for millions. The interpretation of history in the museum is from a Bengali Bangladeshi perspective and the narrative is largely that of the victims and sufferers chronicling their own histories. The exhibition of the collections is geared towards visitors who are mostly locals and might often have a personal link to the war, and for whom, the viewing might aid in the process of healing. There is a deeply ethical element to the museum collections, and, for a visitor who has links to the perpetrators of violence, the collections may inspire a sense of guilt or the desire to undo historical injustices. And even for others who do not have a personal connection to the war, the museum has the potential to be one of the most emotionally perturbing sites of memory they ever visit.

Every museum has a specific social, ethical, and perhaps also a political purpose, and every museum has a story to tell. The story that LWM narrates is one of national suffering that led to the establishment of today's modern Bangladesh. It is a narrative that finds echoes in many of the larger social and political discourses of the country. What is interesting is the ways in which LWM attempts to navigate the challenges of narrating a kind of collective trauma that has been and continues to be narrated extensively and in varied, often contradictory, ways in the larger society.

In the face of increasing number of official apologies and transitional justice movements, memorial museums like LWM have emerged all over the world. Such a museum becomes all the more important for Bangladesh in the absence of any restitution, formal compensation or apology to war victims from Pakistan's end. Museums play a central role in the mediation of memory in the public realm. This becomes even more significant considering that, in Bangladesh, for a long stretch of time, the military achievements of the war became the focus of attention and the civil agitation behind the war lay buried under layers of dust.

LWM presents itself as a storehouse of the memories of ordinary people as well as freedom fighters. Founded in 1996 in the backdrop of civil society agitations for war crimes trials, and at a time when there finally was adequate space for commemorating civilian contribution in the war, LWM memorialises objects donated by victims' families and survivors of the war, in the form of photographs, daily use objects and family heirlooms. Many of the exhibits are mundane objects but they each tell a memory story, often a deeply distressing one. For instance, the museum displays burnt wood pieces from Khan-house of Keraniganj near Dhaka, which, the visitor learns, was set on fire by the Pakistani army on November 25, 1971. Another display holds a two anna coin donated by Md. Zillur Rahman Jamil, and the note beside it informs us that this coin was paid to a young boy by a Pakistani soldier in exchange for a can of milk inside what seems to have been one of the army rape camps. The boy, we are told, never spent the coin as he could not get that scene out of his mind.

The museum website has an open call to people to donate objects of relevance to the museum. For a museum that aims to tell the story of people's sufferings, crowdsourcing of objects seems to be a befitting approach. With the name of the donors mentioned beside every exhibit, visitors get an impression of interacting with survivors and victims' families instead of museum curators. Such participatory culture fits in with the aim of creating a sense of citizenship through shared suffering, and, in some ways, breaks down the walls of elitism around museums.

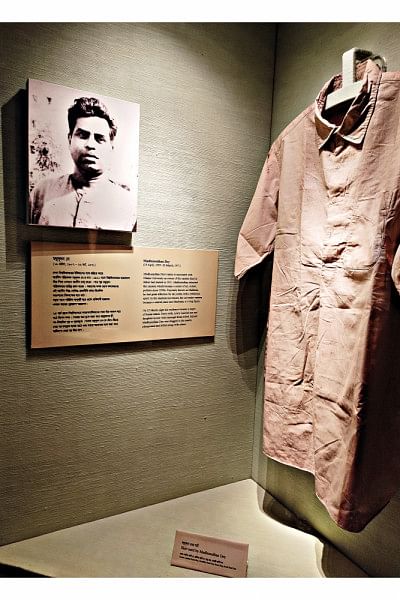

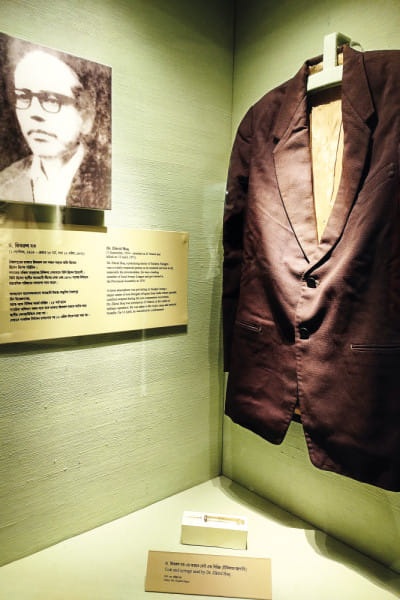

As mentioned in the mission statement of the museum, it aims to commemorate not only the suffering but also the heroism of the people, which, together, generates the discourse of martyrdom. The discourse of martyrdom in any culture is fraught with many complexities and can be interrogated at great length. Leaving that aside for another time, one might shift attention to how the museum exhibits offer an entry-point into this discourse through material memory. The galleries are designed in such a manner that there is an impression of allocation of similar space to all martyrs' contributions as the museum exhibits similar objects like monochrome photos and clothes for all victims, whether they be civilian, military participants or those who accidentally came under the wheels of history. This humanises the dead, personalises history and emphasises the individuality of each victim instead of them being reduced to statistical data.

The differing social status and professions of various martyrs is also made evident through the various objects displayed. There are social and vocational clues in the memorabilia. For instance, the museum displays the art works of Bhupatinath Chakraborty Chowdhury, a mentor of music and art. His artwork is accompanied by a narrative of him being compelled to perform during his interrogation by the Pakistani army. Not only material memories of those who died but also those of individuals who contributed in their own ways towards the war efforts are exhibited in the galleries. For example, the museum preserves a radio receiver used by Ejaz Hussain to monitor news broadcasts from which information was later used for Swadhin Bangla Betar. This serves the museum's purpose of illustrating the contribution of the entire population towards the liberation of the nation. The narrative comes across as one in which everyone is united, putting aside differences in class and social backgrounds. The exhibits are doubtless filtered and mediated through the museum curators, but the crowdsourcing of memorabilia visibly adds an element of egalitarianism to the display. In a way, the museum, like the formation of Bangladesh, is also presented as an outcome of its citizens' efforts.

What LWM offers is a very physical and dramatic experience of the war. Using various media, through effective lighting, architecture and accompanying narratives, it appeals to the visitor's sensory faculties. This contributes not only to the visitor experience but also adds to the meaning of the site. For instance, one of the galleries includes a dark room with dimmed lighting in which the displays are behind wired nets, and an army truck glares at visitors with its headlights on. On several occasions, I observed visitors, including chattering school students on a day trip, being stunned to silence at the sight of the army truck. Even if they were visiting casually, the very tactile experience brings in an awareness that they are engaging with intensely traumatic memory in some form, even if not in the form of conscious critical engagement. Another gallery has an entire wall covered with poignant photos from wartime refugee shelters in Kolkata in which entire families lived inside concrete sewage pipes. What makes the viewing experience even more intense are similar pipes projecting out of the gallery walls. Even though some of the exhibits may be small objects which may seem minor and inconsequential in terms of their economic value, like the coin donated by Md. Zillur Rahman Jamil, but they serve to tell deep affective stories.

The museum was located in a residential building in Segunbagicha since its foundation in 1996 but has now shifted to Agergaon in 2017. Earlier, insufficiency of space necessitated that only 1300 objects could be displayed. How does the physical experience of visiting LWM change now that it has moved to a spacious modern building with twenty-first century architecture and advanced technologies? The knowledge and the space enter into a combination with each other to create the physical and emotional response to the museum and its collections. Is the modern building, with its elevators and its glass doors, representative of a new modern Bangladesh that is built on the foundation of its past traumatic sufferings? Is it emblematic of a Bangladesh that is moving ahead with times despite its foundational trauma?

LWM provides a very hybrid space with multimedia engagements where there are photographs, material objects, audios, and videos. Many of the documents in the archives have been digitised and made accessible to a wider audience and international researchers. The museum website also offers access to a virtual tour in which viewers can navigate through various galleries and listen to audio descriptions of artefacts. It also has a mobile form in which a bus goes around the country disseminating information about the war. In addition, there is active engagement through the various social media pages of the museum. For instance, LWM's Facebook page publishes a 'This day of the year' post every day in which it mentions significant events that happened on each day of 1971. This intense memorialisation through Facebook not only keeps up with digital trends but also facilitates audience experience, contributes to memorialisation and creates meaning in a complex way.

In today's mediatised environment and rapidly changing technological field, the museum is no longer merely a one-time experience, but it instead offers an opportunity to connect via online platforms. It is not just the physical space of the museum anymore, but the museum's activities can be accessed through multiple media platforms, thereby allowing viewers to have varied entry points into the museum's narrative. The museum space is transcended both physically through mobile museums and virtually through online access. Such uses of modern digitisation technologies shows that LWM is evolving with times and adapting to the shifting landscape of modern communication with sophisticated new technologies. One of the main struggles of LWM is to get 1971 internationally recognised as a genocide. Thus, the digital outreach programme, digital reproduction and exhibition might serve a significant role in reaching a wider audience and increasing engagement.

Digital media has become commonplace in museums, not only in the West but also in South Asia. Thus, my intention is not to marvel at the novelty of digitisation in LWM but to open questions about the target viewership of the museum and the societal changes that bring about this need for newness in museological practice. The social media presence and virtual viewing options are not neutral and inconsequential. What are the societal needs that these changes cater to? Is it that the humdrum of our social media life has encroached upon museums? Are museums succumbing to the unquestioned technophilia around us? Or is it that the museums are transcending beyond the space that they have traditionally been limited to? In a nation like Bangladesh where digital literacy is on the rise, LWM's investment of time and resources into digitisation is meaningful indeed.

Museums and archives have always held the power, in the Foucauldian sense, of being storehouses of knowledge. The power to disseminate knowledge of specific memory, to decide what is worthy of remembering, to determine whose archival value mandates preservation. It is interesting to see how LWM exerts its power to create an overarching narrative of the Liberation War. At the same time, it is also interesting to witness the effect that the larger social trends have on its museological practices. Using inventive technology in a museum comes with its own challenges. How to digitise collective trauma without falling into the trap of going overboard, so as not to jeopardise the reverence and contemplation that is aimed for, so as not to trivialize the gravitas of the subject? Populist practices facilitate engagement with the larger public, but it also presents a challenge for museums to not let the populist practices eclipse its larger message. It is to be seen how LWM navigates the difficult terrain of strengthening the legitimacy of its cultural status as a source of authoritative information while, at the same time, opening up the museum space to make it a more welcoming and accessible site.

Madhurima Sen is currently pursuing her DPhil degree at the Faculty of English, University of Oxford.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments