The battle of plassey: A Tale of Triumph and Betrayal

On the afternoon of July 2, 1757, at the hour they were going to kill Siraj in a sodden dungeon of the Jaffarganj Palace—along the east bank of the ebbing Hooghly, flanked by groves of palms, banyans, and mango trees—the young Nawab cast his weary eyes on his assassin before breaking into his final prayer. In the middle of the prayer, he paused a few times to remember things forgotten at his rukhsat altar.

The Revenge of Husayn Quli Khan

'My people,' murmured the wan Mansur-ul-Mulk Mirza Muhammad, 'will not rest to see me retire on a pension, hiding my face in a deserted corner. No, they will not. Then die I must. So, I may atone the death of Husayn Quli Khan … That is my end. And this is the beginning of Husayn Quli Khan's revenge.'

Husayn Quli Khan was a deputy to Nawab Shahamat Jang, the nephew and son-in-law of Alivardi Khan, the Nawab of Bengal, and Siraj's maternal grandfather. Husayn was also the infamous lover of Siraj's eldest maternal aunt—Ghaseti Begum—who could not avert the murder of her paramour by Siraj's men in 1755.

Legends from the Battle of Plassey—fought less than two years after Husayn Quli's murder and a little over a week before Siraj's—can become the touchstone of tragedies 'rivalling the Mahabharat at its most epic and macabre; it can also inspire Marquez to pen another Chronicle of a Death Foretold.' One may even add a grisly Francis Ford Coppola 'family' saga to that inventory.

However, Plassey was and remains much more than these, or the revenge of Siraj's political victims. It is one of the grimmest examples, in modern recorded history, not necessarily of the birth of colonial rule (as most others would claim) but of the episodical phenomenon of South Asians defying the interests of their own imagined community to betray the reins of their statecraft to Machiavellian magnates.

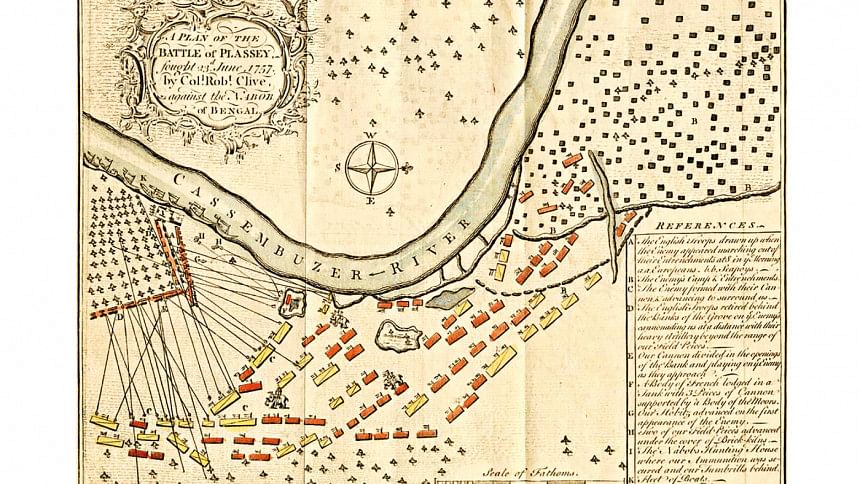

The Last Kedgeree

On June 23, 1757, the Battle of Plassey witnessed the bewilderingly absurd takeover of Bengal by Robert Clive's army. The army consisted of approximately 3,000 troops (including 9 cannons, 200 Topasses, 900 Europeans, and 2,100 sepoys), while they faced a Bengal army that was twenty times stronger. The Bengal army comprised about 50,000 infantry, 15,000 cavalry, soldiers, 300 cannons, and 300 elephants.

George Bruce Malleson, in The Decisive Battles of India (1885), styled Plassey as the most inglorious English victory. It was "Plassey which necessitated," he remarked, "the conquest and colonization of the Cape of Good Hope, of the Mauritius, the protectorship over Egypt; Plassey which gave to the sons of her middle-classes the finest field for the development of their talent and industry the world has ever known … the conviction of which underlies the thought of every true Englishman." It was Plassey, nevertheless, that also exposed South Asia's internal slanderous plots and inequities.

As another Victorian author, George Alfred Henty, wrote in 1894, "the whole of the circumstances that followed the signature of the treaty [of Alinagar in February 1757], the manner in which the unhappy youth was alternately cajoled and bullied to his ruin, the loathsome treachery in which those around him engaged with the connivance of the English, and lastly the murder in cold blood, which Meer Jaffier, our creature, was allowed to perpetrate, rendered the whole transaction one of the blackest in the annals of English history."

It has become almost customary for accounts of the Battle of Plassey to chart the historiography of events between the incident infamous as the alleged 'Black Hole of Calcutta' (June 20, 1956) and the battle of June 1757—that Manu Pillai has termed as the 'war that defined modern India.' The events following the battle make the betrayal of Sirajuddaulah even more palpable.

Two weeks after the Eid-ul-Fitr in the Islamic lunar year 1170—or 1757—Nawab Sirajuddaulah was captured by the troops of Mir Qasim. That was eight days after the Nawab succeeded in escaping from his palace in Mansurganj, following the news of desertion by his troops at Plassey. He ordered his men to disburse liberal sums from his treasury to whosoever had any demand on it. Siraj wanted no man to be turned away, doubtless, inspired by his repentance. Finding himself abandoned, Siraj, then, prepared for an unholy exodus. The coaches and the palanqueens and the elephants and the furniture and the jewels and his consorts, including his favourite Lutfunnisa Begum, were readied in haste. At the stroke of three, on June 25, those loyal unto the last followed the Nawab, leaving Mansurganj for good—or for Robert Clive or Mir Jaffar.

The flight of Siraj was meant to take him to Rajmahal. But instead of proceeding with his plan, the retinue was redirected to Bhagawangola, about fifteen miles away from Mansurganj. As the Nawab set sail from Bhagawangola, he sent a missive to one of his men—Mushur Lass—whom he had given charge of the treasury. By the time the message was delivered, and Lass came to the Nawab's rescue, all left of the latter was history.

Siraj and his retinue decided to anchor at the shore of Rajmahal for an hour to rustle up some kedgeree for stomachs that had fasted for nearly three days. The Nawab's luck frowned on him yet again. Not far from the riverbank lived a fakir, called Shahdana, who was once insulted by Siraj. The fakir—whose name meant 'the royal seed'—promptly enlisted himself as one of the hands preparing the last supper for the Nawab and his people, while he whetted his appetite for revenge. On the sly, he sent a courier to Mir Qasim and Mir Daad. No time was wasted before they arrived.

The Door of the Traitor

Siraj was made a prisoner along with Lutfunnisa. Mir Qasim seized their casket of jewels, while Mir Daad laid his hands on other women. Taking the cue from their masters, their men seized whatever was left of the possessions of the leftover men and women. The Nawab was taken and held captive at Jaffarganj, condemned to beg for a plot of earth and a pension to live off, until mercy came in the grisly shape of Mohammady Beg.

Beg's axe smote the Nawab unnumbered times, scything him to fractions, leaving behind a still dead imperial head crawling upon its own blood. Before the dying eyes could make one last desperate attempt with quivering hands to balance the severed mass they protruded from, they were enveloped by the veil of final darkness. The whispering multitudes of Hooghly and the shifting foreshores of the Bhagirathi swelled forward and backward like an old wives' tale; or like a black hole, where all stories of humankind are headed, like beetles of a marsh into a quicksand.

A little over a mile from the dungeon where those eyes had frozen, Mir Jaffer lies buried, in the Jaffarganj cemetery, which contains the tombs of several Nawabs of Bengal who succeeded Siraj, his treacherous and supposedly cowardly uncle and the latter's treacherous and supposedly cowardly son-in-law. Mir Jaffer's father Syed Ahmed and his widows—Mani Begum and Bubboo Begum—were also interred here. So was Nawab Ali Vardi Khan's sister Shah Khanum, another widow of Mir Jaffar. Here also lie his sons, Ashraf Ali Khan and Mubarak Ali Khan I, as does his great grandson Mubarak Ali Khan II.

The cemetery was built by Mir Jaffar himself, opposite the Jaffarganj Palace, from where he controlled the musnud of Murshidabad—although it was at the Mansurganj Palace where he was to declare himself the Nawab of Bengal in the late June of 1757.

In Mir Jaffar's own lifetime, the palace was cannonaded and bastioned with watch towers. A few desiccated skeletons of the old walls and bared ribs of the old brickwork are the only sentinels left today of the erstwhile palace where a clandestine conference before the Battle of Plassey was conducted between him and William Watts, the East India Company's chief agent at Cossimbazar—the conference where Jaffar indicated to Watts that he would henceforward be Clive's stooge. Over the years, the entrance to Jaffarganj Palace would be renamed as the Namak Harami Deori—the Traitor's Gate—by which name it would also be accepted outside India.

A Historian's Testing Ground

The Battle of Plassey may seem like an overtold saga, as seen in the most recent eponymous book by Sudeep Chakravarti (2020) and the reprinted edition of Brijen K. Gupta's classic, Sirajuddaulah (1966; 2020). However, there are good reasons why it will continue to serve as a virtual laboratory for shaping the historical consciousness of South Asian minds.

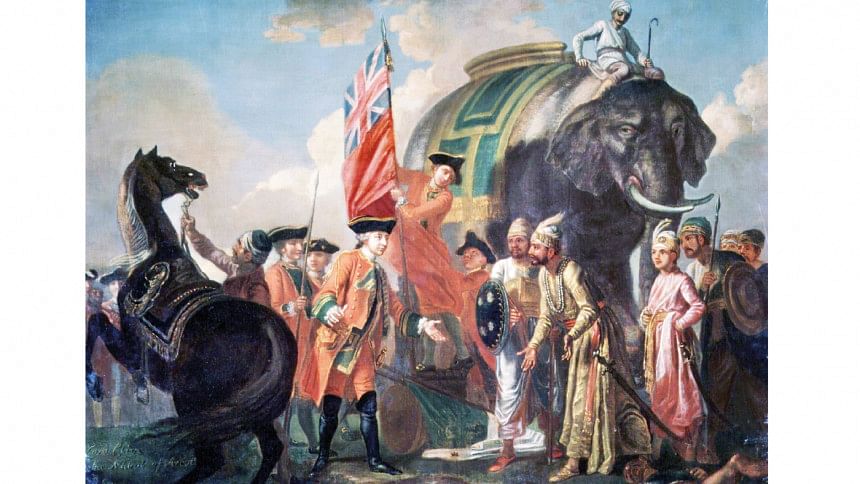

Sirajuddaulah's defeat led to the East India Company receiving a sum of about Rs 23 million, as damages, besides close to Rs 6 million as cash presents, and Clive himself pocketing a fief of Rs 300,000. Fifteen years later, this amount and his other receipts from the conquest impelled him to asseverate before a British Parliamentary committee, "Mr. Chairman, at this moment, I stand astonished at my moderation."

Between 1757 and 1765, the Company's factors exploited the political instability of Bengal to reap profits in excess of Rs. 20 million, while the Company grew richer by Rs 100 million, not to mention the establishment of a British mint in Bengal and the diminution of bullion imports—that amounted to over Rs 70 million before the battle—into Bengal.

The monopolization of saltpetre—the principal ingredient of gunpowder—and, besides an annual profit of Rs 300,000 on its trade, its key role in British predominance over the Dutch and French in the subsequent decades, was another direct corollary of the battle.

Finally, the English company's dexterity at pitting Sirajuddaulah against his uncle Mir Jaffar, and Jaffar against the latter's son-in-law Mir Qasim, heralded a series of strategic victories against Shah Alam II of Delhi, Shujauddaulah of Oudh, and later the Marathas (who, back in the eighteenth century, were armed to repel the advancing armies of Ahmad Shah Abdali).

The granting of the Diwani of Bengal to the company, in 1765, parted the province in terms of its economic and military benefits, making it the perfect launching ground for the project of colonization.

These economic and political fallouts of the Battle of Plassey—then considered far less important than the third Battle of Panipat (1761) fought between Maratha confederates and Abdali's troops—have perhaps assumed an epic proportion in various popular narrations across colonial and postcolonial times. Nevertheless, more than ever before, they are now bound to be mapped against macropolitical transformations that were changing Europe, as intensely as Bengal's changing micropolitical configurations.

The Battle of Plassey occurred during the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) involving European powers, most prominently the French and British, who protracted it to their Indian conflicts in the Carnatic and Bengal. For nationalist historians like Jadunath Sarkar, the English victory at Plassey marked the onset of Bengal's 'Renaissance'—a view also shared by Rabindranath Tagore's industrialist ancestor—Dwarkanath Tagore. But subaltern voices are often absent from the remit of such grandiloquent assertions, their nobleness notwithstanding.

Imperialist historiography, says Rudrangshu Mukherjee, has been 'prone to depict Sirajuddaulah as a reckless villain,' given to mindless plunder. Hence, Clive's conspiring with powerful bankers like the Jagat Seths (nicknamed the Rothschilds of India), merchants like the Sikh Omichund and Armenian Khwaja Wajid, and Siraj's uncle, may be hastily interpreted as the triumph of a conniving despot over a vainglorious one. This, line of reading, invariably betrays an unconscious obsession for seeking karmic meaningfulness in and around the forged battleground at Plassey.

The chronicle of Sirajuddaulah's final days, on the other hand, tells a different story. The last 'independent' Nawab of Bengal probably took his personal downfall as a sign of the stereological message that his imminent death was the revenge of his victims. His antagonist, the certifiably unstable Clive, however, was willing to let his destiny be absorbed into the changing colours of an intercontinental war, wherein Plassey was akin to a scintilla, before it became deeply consequential.

Arup K. Chatterjee is a Professor of English at the Jindal Global Law School, OP Jindal Global University.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments