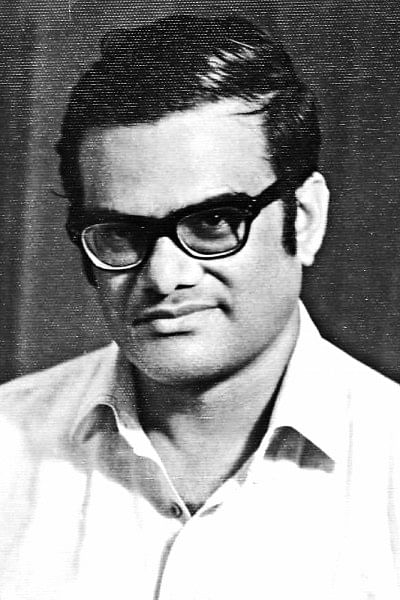

ALAMGIR KABIR: The conscience whipper

Alamgir Kabir's death anniversary has been an occasion to celebrate and remember him as a prominent film director and tireless film society activist. But an important part of Alamgir Kabir's continuing influence in contemporary Bangladesh can be traced back to his film criticism and his approaches to teaching film. Kabir's extensive criticism and film education in the 1960s remains a significant foundation for cultural criticism, film movements, and formal film language in Bangladesh today.

In the early 1960s Alamgir Kabir spent a number of years in London, where he moved in left wing and revolutionary cultural and political circles. During this time, he became convinced of the power and possibility of the cinema. He saw film as a medium of transformative possibilities, its very formal or artistic language capable of galvanising change. Training in formal film language became, perhaps counterintuitively, a key aspect of Kabir's political aspirations. Kabir brought these convictions back with him when he returned to Dhaka in 1966.

The national popular of 1960s East Pakistan to which Kabir returned was deeply informed by leftist and anti-imperial motifs, rhetoric and themes that were inherited from the anti-imperial and revolutionary cultural movements of the 1940s as well as emerging in tandem with wider international artistic networks. Culture had become a site where underground workers and fellow travellers met and where cultural organisations were 'fronts' in the struggle towards social transformation and revolution in East Pakistan. In the course of the 1960s, cinema emerged as one of the art forms through which progressive and left political commitments could be expressed. Today aesthetic traces in the films of the period provides access to the broader alliances and commitments across political and artistic communities that imbued the atmosphere in 1960s East Pakistan.

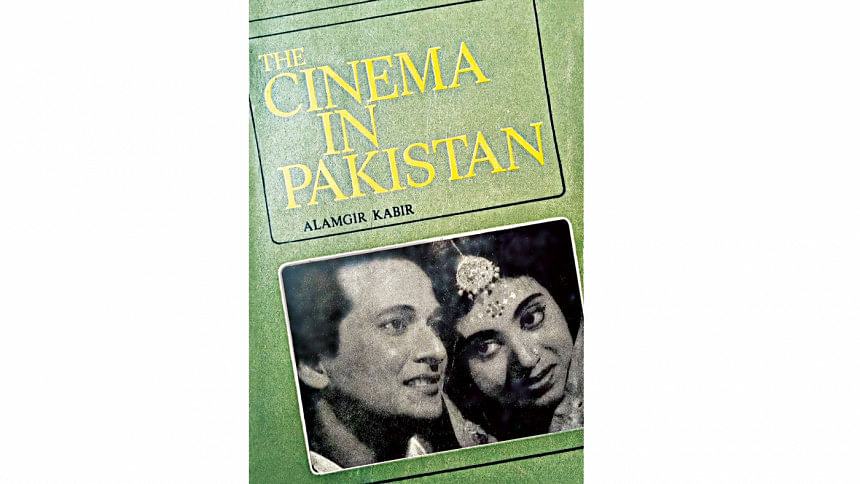

Surveying Alamgir Kabir's writings from the mid-1960s reveals his perspective on the cinema as a socially progressive force and the film critic as the vehicle through which it might be amplified. As he writes in the opening pages of his 1969 book The Cinema in Pakistan: "The cinema is probably the only art form whose political utility can be comparable to that of any political party, may be even more" (5-6).. It was self-evident to him that "the aim of every art is … to act as a catalyst in the process of social evolution" (125). The film critic had a key role to play in catalysing such social change: "A concerted press campaign in favour of good films that try to tell sensible stories without forsaking the needs of the society … and films that make honest efforts to exploit the resources of the cinema as vehicles of art as well as means of propagation of ideas […] could act as an important conscience-whipper of audiences throughout the country" (184). Through publishing his critical evaluations of contemporary cinema in widely read newspapers and by initiating film educational initiatives, Kabir encouraged a reading and viewing public to be familiar with cinematic form, style, genre and convention. He believed that such knowledge would transform established ways of seeing and judging and that this would eventually generate political and social transformation. That is, Kabir understood formal or artistic literacy as a political position. To read Kabir's reviews and critical writing in the newspapers is to witness the ways in which he creates a public pedagogy of emancipation around the cinema. It is to witness the conscience-whipper in action.

Kabir's film criticism was focused on connecting the formal aspects of individual films to their political potential. In the year of his return, Alamgir Kabir reviewed Khan Ataur Raham's film Raja Sanyasi (1966) for the weekly Holiday. Kabir writes that "two elements of his direction impressed me. These are: a precise sense of proportion which is rare in this country and a potent sense of social consciousness. Obviously, he doesn't belong to the school of 'art for art's sake.'… he didn't miss any opportunity of injecting as many social comments as he found possible." This is high praise for Khan Ata's second feature film. The significance that Alamgir Kabir attaches to cinema as an art that is not produced just for its own sake, and that is imbued with social conscience, can also be seen in his review of international cinematic trends, including the nouvelle vague and the Indian neorealists. His evaluations hinge on the question whether the abstractions in films "can make art really indispensable to the toiling millions," as he put it in the Pakistan Observer in 1966. He therefore expresses great appreciation for Chris Marker and Jean Rouch but does not hesitate to critique Satyajit Ray: "Ray is never found to portray the 'evil' or 'violence' that are the real by-products of any society" while "his social commitments are also too feeble, if not reactionary" (Holiday, 17-06-1966).

The realism and social commitment that Kabir finds so important in the films he reviews are directly linked to how he understands cinema's functioning as a medium. For Kabir, cinema is a provocation that demands a response from its viewer. He suggests that the movement of the image produces alongside it a political velocity: its present-ness (happening right now!) has the force to move us, render viewers committed, engage their conscience. And this is what produces its political potency. The 'formally literate filmgoer could translate the film's galvanising movement into an understanding that settled into their consciousness where it would inspire action. A realist film containing social commentary would provoke its audiences in socially progressive ways, 'whipping up' their conscience. But a 'feeble' film would waste its progressive potential.

Film education was the second pillar in Kabir's project to realise cinema's political potential embedded in its formal qualities and animated by its physical movement. It was the trained or 'keen' viewer who would be best able to harness these qualities. Kabir was committed to produce such viewers not only through his prolific film criticism but also through his manifold initiatives towards film education. Like criticism, film education was a means of producing accessible links between people and art forms that were premised on inviting people to pay close attention to the formal aspects of the cinema. And the way to invite people into this body of filmic knowledge was through cine-clubs.

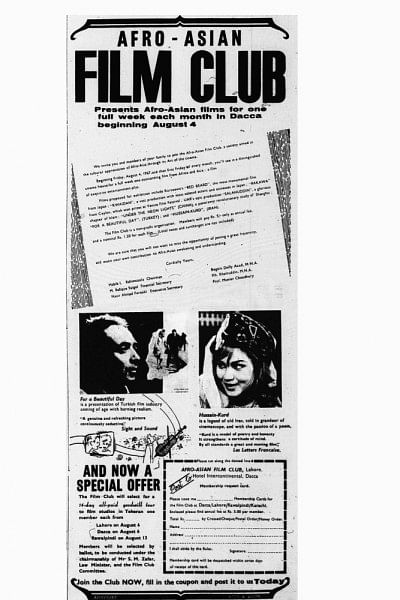

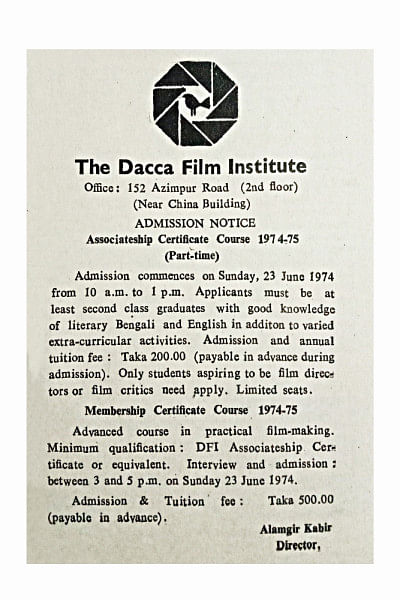

The first film society in Pakistan was set up in 1963 in the mould of the film societies in India and Britain. By 1969 there were two clubs in Dhaka, one in Chittagong and one in Karachi. Not only did the film societies screen a variety of international films for its paying membership, they were linked to a history of radical and progressive political constituencies and put into practice their understanding of the cinema as socially transformative. By 1968, Alamgir Kabir was the General Secretary of the Pakistan Film Society. In 1969, Alamgir Kabir founded a parallel organisation, the Dacca Cine Club and was on the board of directors of the Dacca Film Institute set up at the same time.

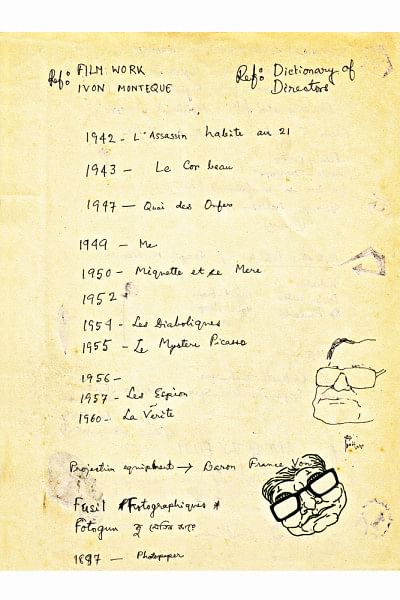

Kabir taught a rigorous curriculum at the Dacca Film Institute. If, in 1970, you wanted become an associate of the Dacca Film Institute, you were required to sit four exams, each taking three hours. The four papers covered cinema history, international cinema, documentary, and, of course, film criticism. The exam papers from that time provide clear insight into the types of knowledge and practice Kabir expected of his students: close textual study, detailed technical knowledge, a good grasp of the political nature of film, extensive historical awareness with regard to cinema in Pakistan, a grasp of film theory and an intimate familiarity with the classic film texts of a recognizably international film canon.

Kabir's efforts in the 1960s were to ground film education in independent Bangladesh in crucial ways. But his socialist vision of a state-run film industry came to naught due to numerous circumstances. Instead, the aspirations for the radical transformation of cinema remained located among film society activists and film educational initiatives, many of which were spearheaded by Kabir. Alongside others such as Mohammad Khusru, Kabir remained a driving force of the movement around cinematic art that emerged after the Liberation War. The movement pushed for the state's support in developing film culture, leading to the establishment of the Bangladesh Film Institute and Archive. Kabir would continue to lead film appreciation courses at various institutes from 1979 into the 1980s and heading the efforts of the Short Film Forum, decisively shaping a new generation of filmmakers, film critics and film enthusiasts. His curricula have become the basis of the many film appreciation courses taught across the country today. Through these curricula, film appreciation, as the practice of evaluating film texts through close reading and formal analysis, has remained the mainstay of film education in Bangladesh and continues to feed into film and media criticism today. It is here that the histories of politically progressive and left-wing cultural politics have sedimented and remain available for contemporary articulation in the film and media culture of Bangladesh.

Placing formalist aesthetic at the heart of the left political agenda of one of the key cultural activists of 1960s expands how we understand the place of the fine arts within this decade's political struggles. This is the time when film in East Pakistan is a site of experimentation drawing on the cultural and artistic ferment of the period. The contributions of urban artists and intellectuals to the language movement and political struggle have largely been read as bourgeois and nationalist in nature. Tracing what Sanjukta Sunderason and I have called 'the forms of the left' in the works and writings of these actors can identify additional artistic and intellectual orientations. Despite the ways in which we think of the cinema in the 1960s in East Pakistan as particularly concerned with family melodrama and folk features and as a steady build-up to the nationalist triumph of Nawab Sirajdaulla, Jibon Theke Neya, and Stop Genocide, there is a social and aesthetic history of left political commitments of many of its key actors that can be easily recuperated through a closer engagement with these texts.

A central legacy of Alamgir Kabir's film work can be found in his efforts at public film education and criticism. His critical writing in newspapers and his teaching on film contributed to the way in which the formal language of cinema came to be understood and practiced as a politically progressive force allied to left-wing positions on art and aesthetics within East Pakistan. This has been inherited by filmmakers and critics in contemporary Bangladesh and its lasting impact can be discerned in films and cultural movements. Tracing the forms of the left in the work of filmmakers and critics such as Kabir provides a starting point to ask what has happened to that progressive cultural politics, in the cinema and elsewhere, after the independence of Bangladesh, and to recuperate its energies alongside the political movements that shape the contemporary moment.

Dr. Lotte Hoek is an anthropologist based at the University of Edinburgh. This article condenses her contribution to the volume Forms of the Left in Postcolonial South Asia: Aesthetics, Networks and Connected Histories (Bloomsbury 2022) that she has co-edited with Dr. Sanjukta Sunderason. She is the author of Cut-Pieces: Celluloid Obscenity and Popular Cinema in Bangladesh (Columbia 2014) and co-editor of the journal BioScope: South Asian Screen Studies.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments