Hefazat leader's plea: More than just a statement

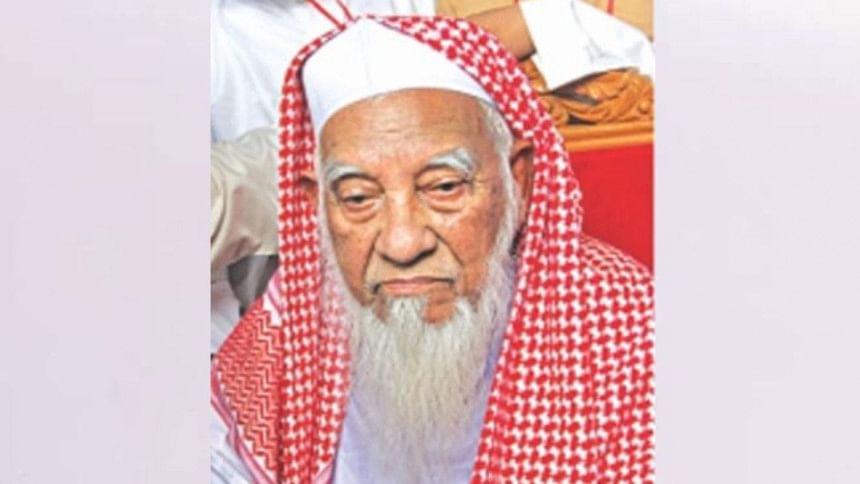

Shah Ahmed Shafi, head of the Hefazat-e-Islam (HI), is in the news again. In a sermon delivered to the parents of the Darul-Ulum Mainul Islam Madrasa in Chattogram, commonly known as Hathazari Madrasa, on the occasion of its annual gathering on Friday, he asked the parents not to send their daughters to school beyond grade IV or V. He not only pleaded but made those present promise they won't send their girls to school. The attendees acquiesced.

The reason for not sending girls to schools, according to Allama Shafi, who is also head of the Al-Hiyatul Ulya Lil-Zami'atil Qawmiya Bangladesh, the highest organisation of Dawra-e-Hadith of the Qawmi madrasa, is that schooling would make girls disobedient. Understandably, there have been strong reactions, particularly in social media. Even those who were either silent or expressed muted reactions when Allama Shafi was in the news last time on November 3, on account of the "Shokrana Mahfil," seem to be outraged by this deplorable call. The "Shokrana Mahfil" accorded Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina the title "Mother of the Qwami" for recognising the highest Qawmi degree as equivalent to a post-graduate degree. In some regards, this call is not inconsistent with Allama Shafi or his organisation, Hefazat-e-Islam. Misogynist statements and demands are hallmarks of HI as well as other conservative Islamists.

The interesting aspect of the call is that it is not a demand to the government to stop women's education. There is no reason to believe that even if it was a demand, it would have been met by the government. Bangladesh has made extraordinary progress in girls' and women's education in the past decades and has become an example of success in the realm of education in South Asia.

One of the key successes is gender parity in enrolment in education. Successive governments since 1991 have made efforts to continue the progress in the education sector. For example, the female secondary school stipend programme, which started as a pilot project in 1982 and later turned into a nationwide programme in 1996, has been exponentially expanded since then under different governments. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been applauded at various international forums for this success. Notwithstanding the concerns regarding the dropout rate and the quality of education, enrolment of female students has increased. There is no turning back. Allama Shafi and his ilk are aware of it. Perhaps that's why they are not making demands to the government. Instead they are trying to sway the public, especially those who are within their reach.

One can take comfort in the fact that this shocking plea will have no bearing on most of the citizens as they will continue to send their children to schools, and the government will not bother going down the road of changing its policy. But one should neither ignore what these kinds of positions imply nor be oblivious to the fact that there is a political dimension to it.

Hefazat-e-Islam is one of the Islamist organisations that profess Islamisation from below, to make a particular interpretation of Islam as the ethos of the society. This has been the modus operandi of social Islamists all around the globe. In many instances, such as this one, there is no religious diktat against female education, but by using the garb of religious education, conservative Islamists tend to provide an impression that they are speaking for Islam. This is not about Islam or its teachings. The statement was made at the annual gathering of a madrasa, an educational institution, and by someone who heads a government-approved body called Al-Hiyatul Ulya Lil-Zami'atil Qawmiya Bangladesh. This gives it a veneer of a knowledge-providing institution.

There is another important aspect to this episode. These kinds of tacit demands, often outrageous, are raised as a bargaining chip. By triggering a particular segment of the population, these actors compel the government to meet other demands. The changes made in the school textbooks in 2017 are a case in point. In the backdrop of the demands of changes in the textbooks being met, Fayezullah, a HI leader, told a New York Times reporter on January 22, 2017 that "The larger goal…goes far beyond textbooks. He hopes to push through a full separation of boys and girls beginning in the fifth grade. Mixing of sexes in the classroom, he said, results in young men and women who 'prefer to live together, prefer to have physical relations before marriage.'" The recognition of the Dawra-e-Hadith degree without any reform in the curriculum and the removal of the Lady Justice statue from the Supreme Court premises are other examples.

Whipping up sentiments with religious rhetoric allows these groups to extract what they want from the government. It becomes difficult, almost impossible, to withstand the pressure, particularly when the public discourse is infused with religious rhetoric and politicians are engaged in a competition to portray themselves as protectors of religion of the majority. Over time, it takes on an extremist tone. The mixture of majoritarianism and religion backed by the state machinery with a populist authoritarian party in power creates a perilous situation. While the political leaders tend to be at the forefront whenever such a situation arises, citizens' uncritical acceptance and acquiescence normalise this tendency. As such, they bear responsibilities too.

The question is: why do the ruling party and the government succumb to the pressure? In the absence of (or due to weak) moral legitimacy, the ruling party is left with little option but to capitulate to any pressure which appears to be powerful. It could be the domestic religio-political forces or coercive state apparatuses or foreign countries. By befriending HI, whether by choice or by political compulsion, and by embracing the religious rhetoric, whether for popular majoritarianism or ideological shift, the ruling Awami League has bolstered the HI and other similar forces in past years. Whether any other party would have acted differently is an open question. But past records of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party suggest that the differences would be of degrees, not of kinds.

Yet, what we know is that appeasement has not mutated the HI; instead, against the backdrop of a controversial election on December 30, 2018, its leader has reminded the country of its presence. It was not quite unexpected—the writing was on the wall before the election. As I had written in an earlier article, "If the next election delivers a government with a questionable moral legitimacy, the influence and the strength of the Islamists are likely to grow further" ('Why are Islamists in the limelight?' Star Weekend, December 28, 2018). It is imperative that we condemn the statement, but we should not be oblivious to the bigger picture.

Ali Riaz is a distinguished professor of political science at the Illinois State University, USA.

Comments