How Bangabandhu flew into London

An unusual secrecy shrouded Bangabandhu's departure aboard a special Pakistan International Airways flight on his release from captivity in West Pakistan. He flew in from Rawalpindi to London in the early morning of January 8, 1972. But the British government was not aware beforehand of his departure for London.

The then British Prime Minister, Edward Heath, termed Bangabandhu's arrival as unexpected, according to a declassified document of the US Department of State. "We first heard of his release in a message from Islamabad which was received when the aircraft carrying him was only an hour away," Heath told the then US President, Richard Nixon, in a message on January 13.

Initially, London was not in consideration as a destination. During discussions with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Bangabandhu had suggested that he should be sent to Dhaka or handed over to the Red Cross or the United Nations. These ideas were not accepted by Bhutto and he wrote to Edward Heath referring to his discussion with Bangabandhu.

Bhutto took over power by overthrowing President Yahya Khan a few days after Pakistan army's defeat in the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971 and announced the release of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in the face of tremendous pressure from the world community.

Bhutto had suggested that Bangabandhu, who earlier had been convicted to death in a mock trial by a military court on charges of waging war against Pakistan, should be sent to Tehran. But Mujib refused to go to Tehran. When London was presented as an alternative, Bangabandhu accepted it.

"He [Mujib] was anxious to reach Dacca as soon as possible and we gave him an R.A.F. aircraft for the onward journey. It was his own choice that he should not transfer to an Indian aircraft in Delhi," reads the British Prime Minister's message for Nixon.

The British Royal Air Force comet jet carried Bangabandhu home via Delhi on January 10 where his people were eagerly waiting for his return.

There has always been a question in some people's minds as to why Bangabandhu flew into London from Rawalpindi.

Dr Kamal Hossain, who was kept in prison during the nine months of the Liberation War and released along with Bangabandhu and flew with him, faced a similar question from the Commonwealth Oral Histories in December 2014.

He recollected that they wanted to return to Dhaka by the shortest possible route, but because of the hostilities that had gone on until December, 1971, Indian air space was closed for Pakistani aircrafts.

"Now I had said, 'Alright, why don't we take a UN plane or a Red Cross plane?'"

"And they [Bhutto and other Pakistani officials] said, 'No, we want to take you on one of our planes - Pakistan International Airlines - and we can't fly over India, so choose some destination which would be acceptable,'" said Kamal in the interview which was posted on the official website of Commonwealth Oral Histories on July 13, 2015. "We said, 'Any neutral country will be fine.'"

The moment the possibility of London was presented, "we just seized it and said that would be best, because many people who come out of exile to participate in the diplomatic efforts in support of Bangladesh were residents there," remembered Kamal, who had held portfolios of law and foreign affairs of the Bangabandhu-led government.

West Pakistan's new President Bhutto saw Bangabandhu off at the Rawalpindi airport amid secrecy.

"The bird has flown," Bhutto told reporters later.

On Bangabandhu's arrival in Heathrow Airport, Bangabandhu was met by a senior British Foreign and Commonwealth Office official in the VIP lounge. Thus, Bangabandhu was accorded head of state protocol.

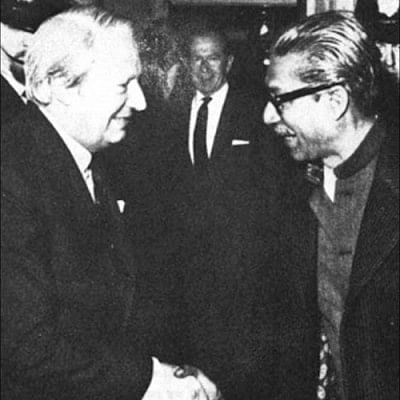

Bangabandhu held a meeting with Heath at 10 Downing Street, residence cum office of the British premier, on the night of January 8. In an hour long meeting with Heath, Bangabandhu raised the question of the British recognising Bangladesh as a sovereign country.

In his message to US President Nixon, Edward Heath said Sheikh Mujib spoke of his hope of Commonwealth membership. "I assured him of our goodwill, but at the same time explained the reasons why we could not recognise Bangladesh at once."

"The problem is one of timing. Too early recognition would antagonise West Pakistan and complicate Bhutto's task," explained Heath.

In the wake of the then ongoing Cold War between the Western and Soviet block, he however cautioned that: "On the other hand, if we delay too long, the Communist countries will get a start on us in the East, and the position of their friends there will be strengthened."

Convinced of the discussion with Bangabandhu, the British premier felt the necessity for recognising Bangladesh as an independent nation. He also suggested that the US president, whose administration had wholeheartedly sided with Pakistan during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971, should convince Bhutto to recognise Bangladesh.

"Anything which you can do to help Bhutto accept the inevitability of recognition of Bangladesh would be most helpful. I am myself in touch with him and have told him that Mujib, in his talk with me, ruled out any formal link between East and West. But your views will I know weigh heavily with Bhutto and his government," Heath wrote.

However, around three weeks before Heath's message to Nixon, Bhutto had sent a message to the US administration not to act in haste in recognising the "so-called Bangla Desh". Bhutto made the request at a meeting with the US ambassador in Pakistan on December 20, only four days after the Pakistan army's surrender in Dhaka, giving birth to an independent Bangladesh, according to a declassified telegram from Embassy in Pakistan to the Department of State.

Bhutto told the US ambassador that he was convinced that sentiment in both wings--East and West Pakistan--was still overwhelmingly in favour of maintaining the union.

Bhutto also made desperate efforts to prevent the UK government from recognising Bangladesh as an independent country. On January 3, at a meeting with the US ambassador, Pakistan's foreign secretary Sultan Khan informed him that Bhutto had told some ambassadors that Pakistan would leave the Commonwealth if the UK government recognised Bangladesh. This view, the foreign secretary said, had been officially communicated to the British government, according to another declassified US embassy document sent to the Department of State on January 3.

The goodwill of the British government as demonstrated during Mujib's stopover in London on his way home from captivity in Pakistan, was, however, maintained as the UK recognised Bangladesh as an independent nation on February 1972. This recognition eventually led to recognition from other European and Commonwealth nations and Bangladesh's induction into the Commonwealth on April 18, 1972.

Thus, after being freed from captivity, Bangabandhu's first meeting with a head of the government, Edward Heath, yielded fruitful results. This shows that apart from being a charismatic leader, he was a great diplomat too.

The writer is senior reporter, The Daily Star.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments