It's a good day to do nothing

I am amused and shocked to see kids, 10 or 11 years old, using all these trendy gadgets. Is their tech-mania so intense, not to mention their schedule, that they need iPads and notebooks and e-books for life management?

Given their schedule, it shouldn't come as a surprise. Herded from school to coaching centre, from there to the music class, weighed down, literally, with books and homework, these kids have hardly any time to breathe.

That's not healthy, according to several studies—such a driven lifestyle can predispose children for hypertension and heart troubles in the long run. Do we need studies to realise these things? I guess we do.

I, am, however, concerned with heart troubles of a different kind.

An overloaded heart simply cannot take its own measure, ear the whisper deep inside, the whisper of its own poetry, its passions and convictions. What will happen to these children with no down time, no time to daydream? How are they going to figure out who they are and what they believe in? How will they know what will make them happy, deep-down happy, not in a crowd—but solo, at rest? That's when you know.

That's what idleness is for—hearing your own voice, singing your own song. But all of us seem revved up to the max, trying to hustle between work and family, struggling to make a living, finding it even harder to live.

Welcome to the end of living and the beginning of survival.

We allow ourselves no respite even in our cars which used to be a grand refuge for drifting and daydreaming. They are now crammed with all the latest, smartest noisemakers, the CD player and the cell phone and the GPS that talk to us. We cannot stand a quiet, idle moment, almost as if we need to keep upping the ante lest there's a moment of idleness, a moment to think.

That's an irony of our lives today—we are never alone, doing nothing, just being—always doing something, working.

But what is work, anyway? The benefits of the hard work of the many go to a small minority of the population, many of whom do no work at all. They have all the leisure in the world. They preach the gospel of work so they can have leisure. In this technological age, it should be possible to distribute leisure more evenly.

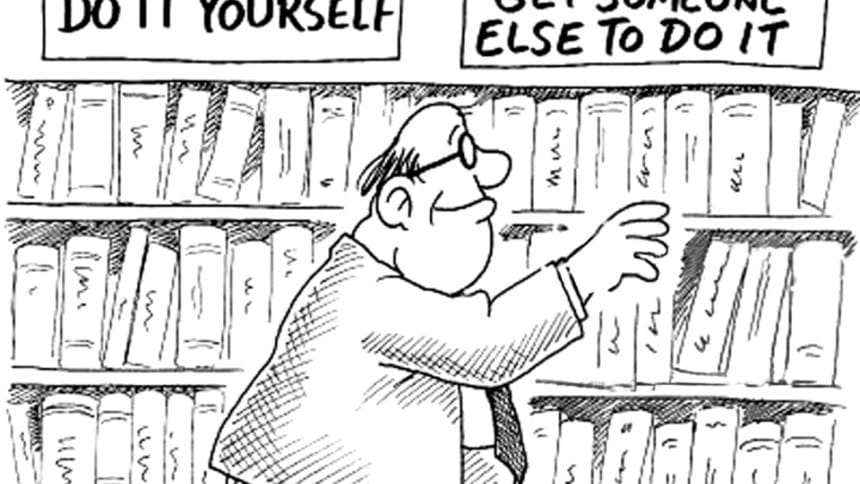

Work is basically of two kinds: first, displacement of matter at or near the earth's surface in relation to other such matter, and second, telling other people to do so. The former is hard and ill paid while the latter, pleasant, easy and highly paid.

The second kind of work is also very interesting; there are those who give orders and there are those who give advice as to what orders should be given. And when two completely opposing kinds of advice are given by two organised claques at the same time, we call it politics. But let's not go there.

The idea that the ones who do the hard work should have leisure has always been unacceptable to the rich and the powerful. In nineteenth century England, the average man's workday was fifteen hours long, even children sometimes did as much. When the urban working class acquired the right to vote, public holidays were established by law, to the great dismay of the powerful. What are the workers going to do with holidays? Keep them working. Hopefully, someday they will stop thinking.

But idleness is the driving force behind civilisation. Only in moments when the mind is left free to roam can we produce thoughts larger than us. Only in moments like these, did humankind discover the sciences, cultivate the arts and define human relationships.

Therefore, this is my wish today: that we all be given the opportunity to idle a bit more. So that in the quietude of idleness, we can think, imagine and dream.

And then, of course, work some more.

The writer is an engineer-turned-journalist.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments