Can China's economic woes derail world recovery?

Since August 11, when China announced that it is devaluating the Yuan, world attention has been trained on China's economy in an effort to understand what is happening in the world's second largest economy. In the wake of recent stock market and currency fluctuations, even old China hands who were sitting on the sidelines have joined the conversation. Financial markets have been abuzz with speculations, and rumours are circulating in the media regarding the true state of China's GDP and other macroeconomic indicators as well as the effect of measures it was undertaking to right the ship. From the flurry of informed discussions in recent weeks, there are indications that China is in more trouble than its officials were willing to admit, and its travails are affecting the economies of its trading partners, including some of its neighbours, and the global financial markets and economic growth in other countries. Even the US Federal Reserve postponed its much anticipated interest rate hike this week, and one of the reasons cited by the Fed Chairman for its decision is the uncertain prospects of China and the Eurozone countries. A larger concern now is whether China's economic condition could worsen and eventually drag down the rest of the world (ROW) or cause major damage to some of its trading partners like Brazil, South Korea, and Australia, among others.

Undoubtedly, the world economy was going through a rough patch even before the recent round of trouble. While the recent decline in oil prices and the concerted efforts by governments and central banks to nudge their respective economies to move forward have had some impact, the results have been somewhat disappointing. Since 2007, when the last major global financial crisis started, the average key interest rate has decline by 4 percent in developed countries and 2 percent in the emerging markets, but the growth rate of GDP has fallen consistently short of expectations. In April 2010, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted that the world economy would grow by 4.5 percent for four years, starting at 2011. The actual growth rate was 3.6 percent. While the shortfall spread across the globe and affected every single country and region, it is stark for India, Brazil, Russia, China, and the Eurozone. Even the US economy, which performed better than ROW and came closest to the expected rate, recently downgraded its forecast for the current year from 3.8 percent to 3.3 percent of growth in GDP.

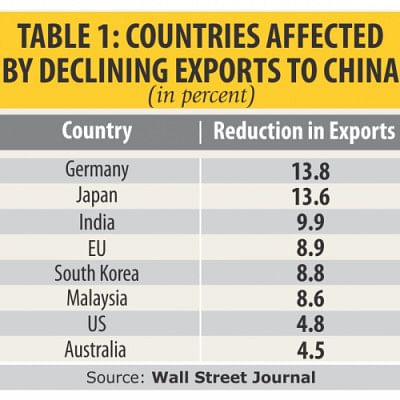

How did this come to pass? In these times of interconnected economies, China's recent economic troubles seem to be the last straw that broke the camel's back. First of all, less growth in China spells trouble for its trading partners. But there is another worrisome development for ROW. China, after years of goading from IMF and US economists, is undertaking a policy shift in an attempt to change its economic growth paradigm. This was prompted by earlier signs of structural weaknesses in China's economy, stemming from its reliance on world market to drive its engine of growth. Chinese economy was faltering even before its condition became acute, which led to the recent devaluations, and has sapped its energy for a much longer time. A comparison of China's imports in July from a year earlier shows that its imports from Germany and Japan were down almost 14 percent from a year ago (see Table 1). China's manufacturing sector has been on a slight downward slide since last year, according to Zhoo Qinghe, an economist with the National Bureau of Statistics. Many economists also doubt whether China, in spite of its pronouncement to keep GDP growth rate at 7 percent, is capable of doing so given that it can no longer count on exports as an engine of growth. In a recent article in UK's Financial Times titled, Doubts Rise Over China's GDP Growth Rate, it was reported that China's economy is really not growing at the level its leaders proclaimed, and its economic statistics seem to operate in a make-believe world. And on top of that, China has announced that it will move away from its export-oriented and credit-driven growth model to one with greater emphasis on domestic consumption. There is no doubt that if successful, this would bring about other policy changes, leading to lower imports, a cause for concern for countries with linkages to the Chinese economy.

The impact of China's economic downturn on other developing and Asian countries as well as in the USA and EU is felt in other ways. Notwithstanding IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde's recent pronouncement that "Asia as a region is still expected to lead global growth", China's economic decline is causing headaches for many Asian countries. One reason is that China's recent devaluations have made Chinese goods cheaper, leading to greater competition for Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam. These countries announced that production of manufacturing goods declined last August. Malaysia's factory index, known as PMI, dropped to a 34-month low in August, falling from 47.8 in July to 47.2 in August. New orders received by Vietnam's manufacturers continued to fall in August, extending the current run of contraction to four months. Brazil and Australia, two countries that are far away from China, have also witnessed major slowdowns. Brazil, a BRIC country, has seen its currency Real decline by 32 percent against the US dollar in the first nine months of this year.

So, what can we expect in the coming months? Much depends on China's ability to bounce back and how its key economic indicators perform: factory production, new orders, hiring, employment, consumer demand, stock market, and exchange rate. Can we say with certainty whether China will drag down the world economy if its recovery falters? The simple answer is a no. With so many factors at play, particularly growth of the Eurozone economy and continued turbulence in Japan and Brazil, one can only keep a close eye on the major indicators and continue reading the tea leaves.

There is a very helpful parable that might help those who like to keep track of gathering storms on the economic horizon. In earlier times, miners would carry caged canaries while at work to give them early warnings of danger in the coal mines. If there was any toxic gas such as carbon monoxide in the mine, the birds would die before the levels of gas reached a level hazardous to humans. What are the "canaries in the coal mine" that could provide similar warnings for investors or economic policymakers? Exchange rates of the Euro and Yuan, price of crude oil, GDP growth in EU, the Fed's policy, and tightening exchange controls in China are clearly early bellwethers of choppy waters ahead. Most importantly, in the coming months, China's ability to put its economy on an even keel would have some impact on the economic outlook for the world as well as for the financial markets.

The writer is an economist and educator who writes frequently on policy issues.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments