AMAN'S ORDEAL

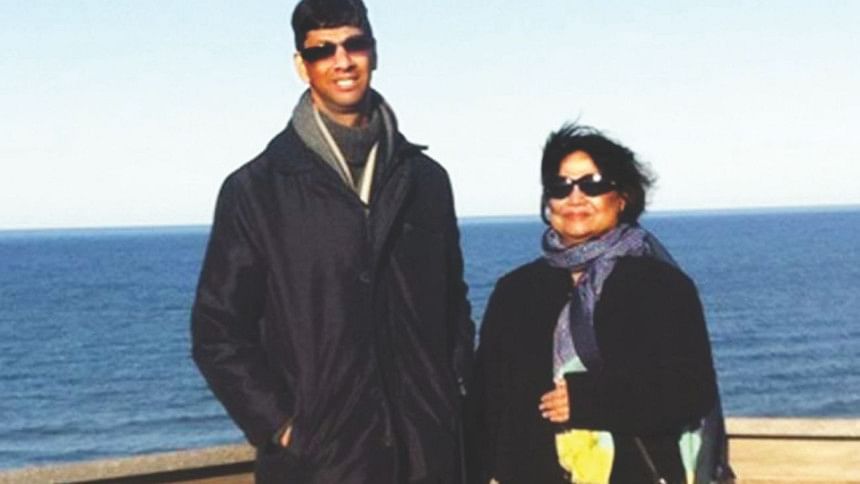

On my saddest day, I see smiles. We buried Aman next to his grandmother and grandfather and his eldest brother, who died at the age of six.

I feel very tired to think this all through. Now I remember; I wanted Aman to be well quickly so that he and I could leave for London at the end of his summer holidays. He had been feeling unwell since our visit to Noakhali. After dinner, his fever flared up, causing immense discomfort. I took him to the United Hospital, where Dr. Afsana immediately pronounced that he had dengue and told us to admit him in the hospital after a basic blood test. His platelet count was 120.

We did. But instead of improving, it got worse. The main concern was that he was sweating a lot and he was having the urge to urinate very frequently which the doctor did not treat. He was given IV fluid and oral saline. His temperature was within 101-102 degrees. On the fifth night, he was given a strong broad spectrum antibiotic by Dr Pradip Saha. He became very sick, sleepless, although he was given a sedative. When I checked in around midnight, Aman was still not asleep; I had left him around 9: 30 or 10pm. When I checked in at 2:00 am and found Aman still unable to sleep, I asked the attendant to pass him the phone. I asked him to go to sleep and he assured me that he would. He sounded normal; I should have asked if anything was bothering him but I did not. That was my last conversation with my son.

I wanted to treat him at home, since there is no medicine other than water and rest for dengue. But the doctor did not allow this. Instead, he gave Aman antibiotics, in addition to Paracetamol and a potassium drink. I could hear Aman wailing from the lift of his floor. I ran to him and there was my son with his eyes rolled up and an anguished cry coming out of him. I held his hand and tried to calm him. His lips were very dry. I gave him half a teaspoon of water and told him to say Allahu repeatedly; he responded by whispering Allahu but did not look at me. The doctor on duty Dr. Afsana who said he should be shifted to ICU for better monitoring. They put him on oxygen only then and took him away. He was not even given oxygen or examined fully and properly.

Moudud came when he was already in the ICU and we were not allowed in. I was asked to sign a paper to allow an incision near Aman's neck line so that more fluid could be given. as he was still dehydrated. Then they came again, asking me to sign another paper to put a ventilator down his throat. My mother had died after she had been put on a ventilator. I could not understand why Aman needed it. Much later we were allowed to see him. His body was lifeless, like in deep sleep. I called him but got no response. When Asma touched him, she said there was a slight sensation. When Khokon and I called loudly, his closed eyes tried to blink a little. During this time, a CT scan and more blood tests were done; I don't know why.

Dr. Pradip was again trying to convince us to agree to give him another series of drugs, this time quinine, which could have a reaction, to treat a type of malaria that Aman might have contracted, though there was no clinical proof of that. Time was running out. I agreed but the medicine was not available.

By now, all we wanted to do was to take him out of this place and get him treated at Mount Elizabeth Hospital in Singapore by air ambulance, which was supposed to be fully equipped to meet emergencies on air. When the doctor said he could fly, we arranged for the flight, which would be a four and half hour one in a very small jet. It took nearly seven hours to get the hospital release papers and bill clearance. During the long four hours, it seemed like Aman was still asleep. They controlled his face muscles with a hand held machine. At one stage, they were desperately looking for something but could not find it. That is when I was convinced that something was wrong. They explained that the patient was losing pressure and he had already exhausted three pumps or something like that. By this time, the aircraft was trying to land in Changi Airport. They should have known that Singapore had announced a national emergency due to heavy haze. After wasting more time trying to land, they flew to the other airport, some 20 minutes away by car. Finally, the air ambulance landed in a deserted part of the airport at around 4:00 am. After or during landing, they started pumping his heart by hand and after a while they asked us to get out of the aircraft. There was no ambulance waiting on the ground. We rushed around, trying to convince the airport staff that this was an emergency and we needed an ambulance.

I then saw one of the medical staff come out of the aircraft looking totally exhausted; I knew it was all over. After four hours the ambulance came. But death on Singapore soil brought scores of police who investigated the death for hours. They said they would have to wait for the supervisor, who came after two hours. All this time we were pleading with everyone to release the body of my son from the oven hot aircraft. We begged to let him be taken in an ambulance to a cool hospital chamber where he could be examined and all enquiries may continue. But they did not listen. He was covered with a dirty blanket in the heat. They were apparently following procedure. After over an hour, he was sent to the General Hospital morgue, where he stayed until the coroner's case hearing the next day. We had nothing to do.

Once at the hotel, I sent an email to Robert Gibson, British High Commissioner in Bangladesh, requesting him to help us collect Aman's body, perform the religious rites and take him home for a quick burial. I made a call to the Bangladesh High Commissioner to expedite Aman's release from the morgue and not to perform an autopsy of his body. He immediately responded and assigned Mr. Ashraf, who not only helped but spent hours following Singapore procedures.

While my son slept in the morgue with the ventilator still on, a symbol of medical malpractice at United Hospital and most probably in most private hospitals and clinics in Bangladesh, I wrote down funeral details and arrangements for our son, defying all religious norms.

Next morning I got a call from the medical agent to inform me that the police officer dealing with our case had asked us to go early to the morgue. He could wait, I thought, after making us wait four hours at the airport after a long flight and a tragedy that will stay with us for life. I was also informed that the British Consulate had been calling to cancel Aman's British passport before office closed. I called the British consulate and they informed me that there was no hurry – I could do that when I reached Bangladesh. Perhaps the medical agent was anxious that there could be an inquiry on possible medical neglect after the death of a British subject.

When we were shown our son's body we cried and begged the doctor to spare him from autopsy. Finally his body was released after two hours and we managed to bring our son home on September 16 and buried him on September 17.

He was a very innocent young man and he should not have been subjected to such humiliation in life and in death by the so called booming Singapore health business. There are many agencies in the name of health packages which are not accountable to anyone. Nor do they pay taxes anywhere. They use the name of high profile hospitals and doctors, perhaps they too are involved. But why did it happen to our son who was the sunshine of our life?

Today we buried him under the Dalim gacher toley made famous by my father poet Jasimuddin's prophetic poem Ei khane. Dalim gacher toley, tirish bochor bhijaye rekhechi dui noiner jaley.

The writer is former MP and President, CARDMA.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments