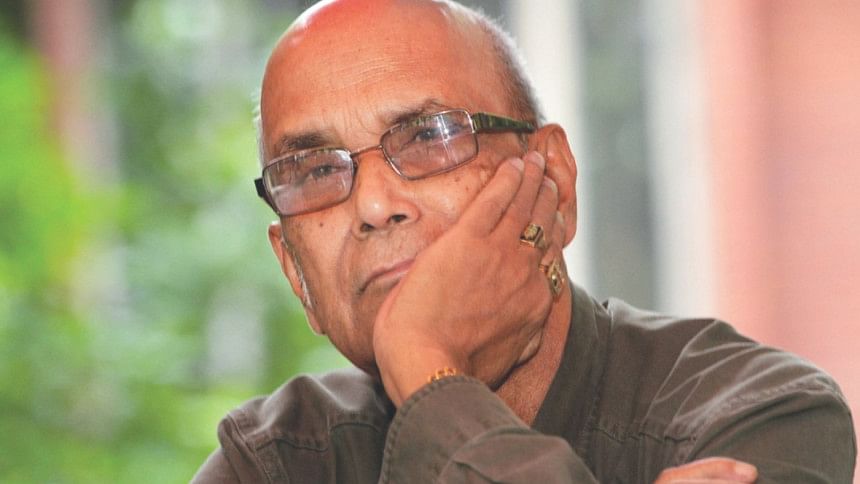

“I am where I thought I would be”

The Daily Star (TDS): You are turning 81 this year and yet you are enviably young; your pen is still at work. What is the source of this amazing vigour?

Syed Shamsul Haque (SSH): About working in every medium- yes, I do that. After all, it is language and language is my medium.

Poetry, prose, novels, plays, these are only ways. I try to convey my words through these ways. Not all of it can be presented through signs and cues. Can we catch all of what is in the mind? Even Rabrindranath could not do that. No writer or artist could. A distance always stays from what is in the imagination. In that sense, I keep trying through signs and cues. It does not feel like the time or the calling to give up has come yet. I am still the same and it feels good. A birthday is not that special a day; 81 years is only a calculation.

This staying alive, life itself is its inspiration. Lalon has said, "Would a life like this come again?" It will not; here, now. The time that I have passed; if I were to be reborn then I would like to come back here, just like this.

TDS: You have been working in many mediums; which one do you think works the best for you?

SSH: The first thing is that my work, in terms of the ingredient, is to work in the medium of language. While working with language, I have worked and am still working in all the creative expressions of language - poetry, prose, novels, and plays. It is that I do not differentiate between mediums. I think I have used the medium which is the most tailored to what I have to say. Sometimes it comes in poetry, sometimes in prose, sometimes in novels, and sometimes in plays. Every medium is strong in its own way.

TDS: Now I want to talk a little on your memoir Pronito Jibon. You wrote in the introduction, "I do not think of any autobiography to be of more truth than a novel." What is your reason behind this thinking?

SSH: About taking refuge in fantasy in an autobiography? I do not think autobiography is more true than a novel, only as true as a novel is; it is true that it could have happened. This is because when we look back at ourselves, we do not see everything in the same light or in the same measure. When we look at our lives, it has colours, it has feelings; we add the references from life with those and try to make something creative. That is what I meant.

TDS: We read Keranio Doure Chilo in Kaler Kheya and Nodi Karo Noy is being serially published in Kali O Kolom. Could you say something about these two novels?

SSH: I have framed time in the novel Keranio Doure Chilo. I think of writing novels as creative journalism; writing the story of time word by word. My growing up during the partition is coming up in Nodi Karo Noy and with that I have tried to tell the story of this issue touching the life of an ordinary person.

TDS: You have witnessed important times such as the British colonial regime, Pakistan occupying regime, the military regime, and independence. How does this feature in your work?

SSH: My assessment will not be like a historian's but I have tried, through my writing, to capture the essence of that era. I was born in a village in Kurigram. I was there until I was 12 years and 3 months old. In my childhood, especially in the times of World War II, Kurigram town, overland, was filled with white soldiers as it was thought that if the Japanese come, they would come by this way. The atmosphere was like that from when I was four to when I was 10 years old. Two events in my life have greatly affected me – the partition of '47 and the War of Independence in '71, which will never happen again in history.

TDS: Tell us about your early life and how it shaped you as a writer.

SSH: Seeing me, some people may think that I am at present what I was back then. In reality, we used to stay in a small house with a bamboo roof and clay floor. My father, penniless, destitute, reached the middle class life after a lot of struggles. We grew up in hardship after my father passed away. We shared whatever we could find with the whole family. We were in darkness but we did not consider it to be dark. We never had any regrets. I always see life from the outside, and also from the inside. For a writer, seeing things from both perspectives is necessary too. Even after being in the midst of so much technology, literature has to be more inbound.

TDS: When did you first realise that you wanted to be a writer?

SSH: When I was in class 10, I thought that I would become a writer when I grow up. There is no other 'historic' reason behind this. So, there is nothing to glorify this. The fact that my father was a writer of homeopathy books might be one reason for the special attraction.

TDS: I read a piece of your writing called Jaleshwari. Is Jaleshwari your place of conscience or a refuge?

SSH: Neither; it is geography. I keep on wanting to write about the people of the village, to write the story. Why does one have to fantasise a new place every time? Rather, I create something on the basis of what I have seen, what I have known, and what I have identified. Jaleshwari was created this way. It is rooted in Kurigram and the adjoining areas. I feel like it is my birthplace. It can be thought of as a literary locality.

TDS: Critics have praised your play Gononayok adapted from Shakespeare's Julius Caesar. Such individuality and spontaneity within such a beautiful translation is rarely seen. What do you think is the secret to a successful adaptation?

SSH: When you are translating something in a language, it has to be like that language. When I translate Hafiz or European poetry into Bangla, it has to reflect nuances of the Bangla language so that it completely becomes a Bangla poetry, instead of reflecting nuances of that country's language.

TDS: We want to know about your philosophy and motivation of life.

SSH: Life has to be driven but strength is needed to do it. This strength is born within one's self. I am being able to take my life forward, everyone is getting older, time keeps going forward, and this is a matter to be enjoyed.

TDS: You are writing romantic poetry even at 80. Please comment.

SSH: The essence of Bengali poetry is love. This comes from Radha-Krishna. And as much as love is in this imagery, there is also eroticism. It is physical in one way and psychological in the other. The principal motif of Bengali poetry is Radha-Krishna. If you read the poetry of Rabindranath and other great poets in depth, you will understand what I mean. That is the motif I have worked with.

TDS: What would you like to say to our contemporary writers and those young individuals aspiring to be writers?

SSH: You have to write in your own way. Writing is a lonely job; you have to keep doing it alone. You have to grow up on your own. Remember that the last refuge of truth is art.

TDS: What are you working on now and what are you reading?

SSH: At present, I am working with two poetic dramas, one long poem and some stories. I am also working on a writing which is a bit different; when a reader reads it, new stories will be formed in his/her mind. I want the reader to be creative too.

At present I am reading some books on history, philosophy and some classic novels. Other than reading, what else can keep oneself going?

Translated by Afsin Trisha.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments