When the waters rise and the food disappears

"Anything, with sufficient intention, could become a weapon."

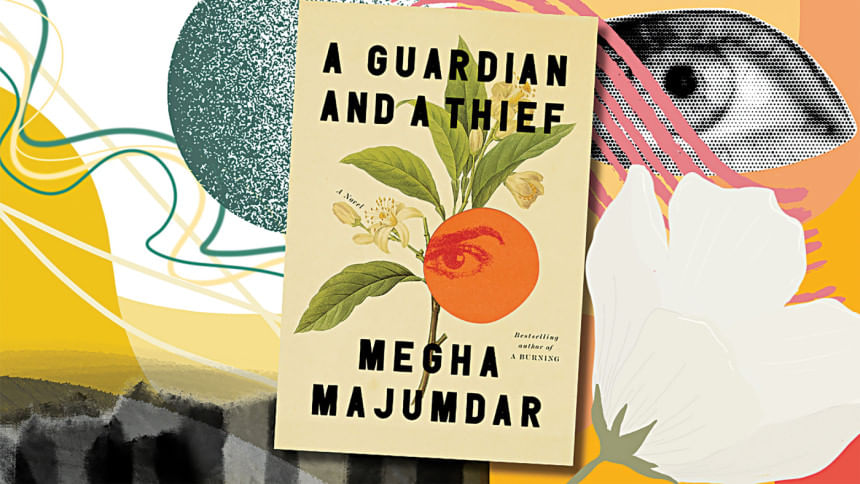

—Megha Majumdar, A Guardian and A Thief

The quote above seems to capture the heart of this novel set in a near-future dystopian Kolkata rendered uninhabitable by political corruption, inequality, and the ominous package of climate crisis–floods, famine, overheating. In Ma and Dadu's desperate attempts to salvage any morsel of happiness and comfort they can for the two-year-old Mishti, in Boomba's relentless struggle to find a sturdy place in the city for his displaced family, one can see the quote peeking out of almost every scene, which rises from the bedrock of urgency.

Ma and her father, Dadu, are scheduled to move to Michigan with her daughter Mishti. Her husband is a scientist there. Because of that, they were eligible to receive a special type of visa called the climate visa after long months of bureaucratic processing. Their passports, however, go missing as Boomba breaks into the house in the dead of night and steals Ma's purse (which carries the passports) alongside food from their stocked pantry. This event triggers a narrative fueled by endless sleuthing and the breathless energy of Bong Joon Ho's 2025 film Mickey 17. It's a narrative where the stakes are constantly being raised high for the four characters (Ma, Dadu, Boomba, and Mishti). Whenever we see a moment of reprieve, Majumdar is quick to snatch it away. Such a propulsive narrative where the odds are insurmountable seems only right in the context of a South Asian nation ravaged by climate crisis.

As I progressed through the story, I couldn't help but see Dhaka instead of Kolkata in the pages. Because these cities are similar in many ways, I felt close to home the irascible nature of civilians who are frustrated with the weather and lack of basic things in a hopeless landscape. I certainly hope her portrayal of a depleted and mangled city isn't prescient, although it's hard to not stare at the prescient element if one considers the desolate statistics related to the climate crisis.

One passage particularly stood out to me because of how it conveys a pervasive sense of hunger in this dystopian Kolkata: "Throughout the crematorium grounds, dogs roamed, tongues hanging, ribs sticking to skin, seeking food in the flesh of those who were gone, and it was only when the loved ones of the dead yelled, "Hut! Hut!" that they retreated."

The novel is rife with passages and scenes like this, not shying away from casting in clear light poignant details of abjection. In doing so, Majumdar's intention of suffusing the pages with nostalgia and longing for a lost time, a time when all the crises were only looming on the horizon and not a tangible part of everyday life, shines through. Consider, for instance, when Ma and Dadu go to the bazar and lament the fact that nobody has had real fish and vegetables in a long time because of the intense salinity in the rivers and the uncultivability of large swathes of the country's farmland.

The novel also succeeds in writing sentimental scenes without being saccharine. The sentimentality doesn't stem from overdone truisms, though. It's profound and laced with refreshing depth. "Perhaps the true adventure was not only in seeing the world but also in seeing the versions of one's own self that the journey revealed."

Another strength of the novel is its economical yet lyrical language that never wanes. It sustains the fast-paced story through and through, making the reader face a difficult choice between savouring the language and turning the pages to see what happens next. This dilemma reminded me of the similar experience I had while reading Ian McEwan's Atonement (2001) and Tahmima Anam's A Golden Age (2007) earlier this year.

The big question the novel is interested in grappling with is: What part of yourself are you willing to lose to bring comfort to your family? This question is the heaviest on Ma, who harbours a shameful secret that will ultimately change her life trajectory, and Boomba, whose past mistakes are stalking him as he lurches from one obstacle to another as an uneducated man with no social mobility. Another question that arises from this one, and is also relevant to, is: Who is truly a guardian and who is a thief? Of course, the novel provides no clear-cut answers. It creates a whirlwind through these binaries between guardian and thief, good and evil, pushing the reader to a dizzying intersection where it's hard to decide whose choices are more ethical in this strange dystopia where a billionaire is developing cooling products to sell to the heat-stricken masses, most of whom cannot even afford those products. In propping up these questions, the novel doesn't feel allegorical, like it's trying to lay out a manual of how things should be done. It feels organic and woven into a tight and cohesive plot by the characters' unique reasonings and motivations, all borne on the shifty carpet of uncertainty and fear. I cannot gauge how the novel's plot came to be so (Is the author an arduous outliner? Or does she play by the ear?). But nowhere does the author's artifice (of making us believe that the story world is entirely governed by her characters and not herself) crack or falter.

The novel also succeeds in writing sentimental scenes without being saccharine. The sentimentality doesn't stem from overdone truisms, though. It's profound and laced with refreshing depth. "Perhaps the true adventure was not only in seeing the world but also in seeing the versions of one's own self that the journey revealed."

If this novel isn't longlisted for the Booker Prize next year, it would be a terrible shame.

Shah Tazrian Ashrafi is an MFA candidate and a graduate teaching assistant in Fiction at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is the author of The Hippo Girl & Other Stories (Hachette India, 2024).

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments