The Tagore women: A step ahead of their times

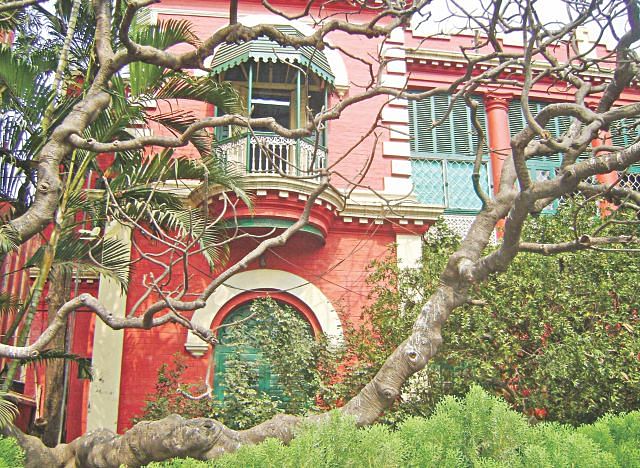

A total of seven hundred people lived in the magnificent Jorashanko Thakur Bari. Photo: Sadya Afreen Mallick

A total of seven hundred people lived in the magnificent Jorashanko Thakur Bari. Photo: Sadya Afreen Mallick

It had been 14 years since we last visited Kolkata. This time around, we were attending the weeklong “Bangla Gaaner Utshab” by Bengal Foundation. One of the first places we decided to visit was Jorashanko Thakur Bari, the ancestral home of the Tagore family, which now serves as the Tagore Museum for Kolkata.

Jorashanko Thakur Bari was built by Prince Dwarakanath Tagore, Rabindranath Tagore's grandfather. Entering the finely manicured courtyard of the three hundred year old mansion was like stepping into the grand era of Bengal renaissance.

A cool morning breeze blew gently as we entered “Bichitra Bhaban” on first floor. I peered through the glass door of the family maternity room, the Atur-ghar. A straw mat on the floor and a lantern nearby was the simple decor of the room where Rabi and his 13 siblings were born. Starting our tour of the house with the maternity room was significant, given the prominent and unconventional role that women played in the Tagore household.

The women in Tagore's family were talented and brought up in an intellectual climate of literary debates and discussions, musical compositions, painting, and theatrical performances. The family flourished in this environment. They had their own system of education and the Tagore women did not go to school but were educated at home. The family environment was such that they set up their own private theatre. The somewhat conservative Maharshi Debendranath Tagore (Rabi's father) had placed many restrictions on family members participating in certain types of activities outside the house. Therefore, they brought the outside world into their house and the entire family, including the women participated.

Like a play being staged before our eyes, I imagined the sound of hooves as Satyendranath Tagore (the first Indian to join the Indian Civil Service in 1864) and his wife Gyanadanandini Devi went off for a horse ride to Gorer Maath. It was an ultra conservative period then, and the sight of the couple on open horseback left pedestrians in shock no doubt. Nevertheless, Maharshi, a strict disciplinarian in all other aspects, did not object. Neither did he object to his daughter-in-law's preference for the car rather than the palanquin, which was the favoured transport amongst the genteel ladies of that time. The conservative society allowed women to take the sacred Ganga Snan in covered palanquins.

A total of seven hundred people lived in the magnificent Jorashanko Thakur Bari. Photo: Sadya Afreen Mallick

A total of seven hundred people lived in the magnificent Jorashanko Thakur Bari. Photo: Sadya Afreen Mallick

A prolific writer, poet and song composer, Maharshi's second son Satyendranath encouraged Gyanadanandini, to adopt western ideas and even attend the Governor's party. Later on she travelled to England with her three children, inconceivable in those days.

Gyanadanandini was to become a pioneer on women's issues on a number of fronts.

Influenced by her stay in Madras, Gyanadanandini brought about a revolutionary change in the manner ladies of the Thakur Bari wore saris. She took evening strolls much like European women, and even introduced birthday celebrations at Thakur Bari. She did adaptations of plays, encouraged painting and even lived separately with her nucleus family, a break from the age-old custom of living together as an extended family. Three of her writings were printed in Bharati at a time when women's education in India was unheard of. She translated “Achchorjo Polayon” from “The Great Escape”, penned numerous contemporary reviews and was highly active in the world of literature. She was also a keen advocate of women and children's education.

Gyanadanandini's infectious passion touched all around her, even years after she died. Indira Chowdhury (18731960), Tagore's niece, distinguished herself in literature, music and the women's movement. She married Pramatha Chowdhury, a renowned scholar and writer. Tagore's collection of letters to her are well known as “Chhinno Patro”. The list does not end here.

Rabi's sister-in-law Kadambari Devi was a great theatre enthusiast and took part in dramas staged at regular intervals in the mansion's courtyard. Her suicide at 25 left a deep scar on Rabi's mind and he immersed himself in work to overcome his grief.

Not to be outdone by the men of the family, Rabi's sister, Swarnakumari became a noted novelist and his sister-in-law, the editor of a magazine. Swarnakumari outshone her contemporaries, barring Bankim Chandra and Tagore, by writing her first novel “Deepnirbaan”. She was prolific in her work, writing memoirs, theatre adaptations, musicals, and travelogues. She also edited a children's magazine, Balak. Her husband Janakinath Ghosal was one of the founders of the Indian National Congress and she took an active part in his work. She took up the issue of widows, from a woman's perspective and initiated the first women's organisation 'Sokhi Samiti', run by educated widows, and also provided them with jobs as house tutors.

Traditional housekeeping, tailoring, needle craft, cooking, taking care of family, playing cards and pasha, adda, child care, observing traditional festivals like Boshonto Utshab were all part of the normal routine among the ladies of the noted family.

Then there was Hemendra who taught his wife music and Nipomoyee also painted with a natural flair.

Hemendranath was entrusted with the responsibility of overseeing the education of his younger brothers as well as administering the large family estates. Exceptional for the times, he insisted on a formal education for his daughters. He not only put them through school but also trained them in music, arts and European languages such as French and German. He actively sought out eligible grooms from different provinces of India for his daughters and married them off in places as far away as Uttar Pradesh and Assam.

The Jorashanko Thakur Bari seemed to have soaked up centuries of history. Every room we stepped into seemed to have a story. A story not only of Rabindranath, but also of a family that had defied the times and helped usher in a new age in Bengali culture -- a culture that pushed women into the forefront, rather than continue to keep them on the fringes. Rabindranath may have been the bright sun to have shone on Jorashanko, but he was certainly in the company of a brightly lit galaxy of stars.

Sadya Afreen Mallick is Editor, Arts & Entertainment, The Daily Star

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments