To centre stage from the fringe

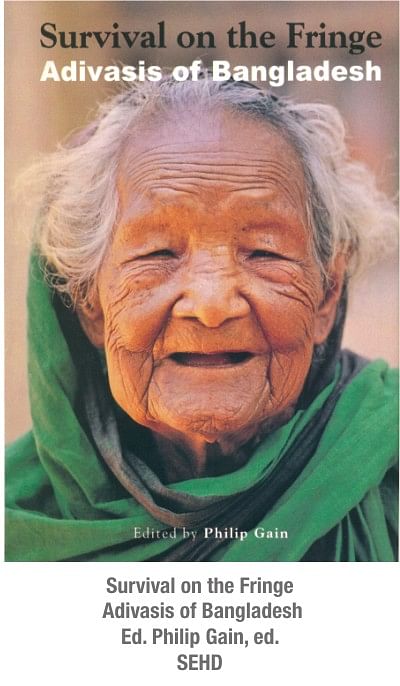

This is a difficult book to review, but, strangely enough, also a relatively easy one. Survival on the Fringe: Adivasis of Bangladesh is a 600-plus-page tome whose dizzying array of topics relating to the indigenous people makes it a taxing task to take stock of within a limited space. However, the editor, Philip Gain, has simplified the task by presenting a thoughtful and comprehensive introduction ("An Introduction to the Adivasis of Bangladesh") that encapsulates in twenty four pages the diverse contents of the rest of the book. The entire book and the introduction are monumental efforts in presenting the sometimes misunderstood, often partially understood, at times totally ignorant of, and ignored, life and society of the diverse indigenous people inhabiting Bangladesh. The entrancing cover photograph of a Garo woman who was reported to be over a hundred years old when photographed in 2006, gives one a partial insight into the editor's passion. He is an avid and accomplished photographer and a vigorous advocate of upholding and advancing indigenous rights as a distinctly minority community with its own cultural and societal norms, traditions, and practices. Gain is Director, Society for Environment and Human Development (SEHD), an NGO, researcher, freelance journalist, and adjunct faculty teaching environment communication in the Department of Media and Communication, Independent University, Bangladesh.

Gain is forcefully forthcoming in his comments and opinions. That expectedly would ruffle more than a few feathers, but that is beside the point. Some things need to be said out loud and clear for driving home a point, and the editor does not disappoint in making his opinion known. He draws on Claus-Dieter Brauns and Lorenz G. Loffler's striking observation of indigenous diversity within a compact space, "If there is anywhere on earth where one can find within an area of few square miles several groups exhibiting distinctly different cultures, then it is in certain regions of the southern Chittagong Hill Tracts. Here within one and the same mouza, one may find four groups speaking completely different languages, building different types of houses, wearing different clothing, and following different customs of different religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, Christianity and Animism)." And then expands it to record his own observation, including a thinly-veiled censure: "The Adivasi groups in other areas of the Bangladesh (sic) --- Northwest, North-center, Northeast and the coasts --- are also no less diverse culturally, linguistically, and ethnically. Despite being stricken by poverty and under pressure to adopt the lifestyle of the Bangali majority, they try to stand strong, show the riches of life, and some appear to be demonstrating the role models before the homogeneity of patriarchal and Bangali Muslim society. Think of the matrilineal Garo society where women own property, do everything, can independently choose their husbands...with any air of freedom, in sharp contrast with women in the Bangali society."

The phalanx of writers contributing to the book goes with a mix of incisive, indifferent, and sub-par individual writing into the nitty-gritty details to give body to Gain's thoughts outlined above. The mission statement regarding the book is provided in the Preface: "This book has been designed to contain facts, anecdotes, and analyses both to give a map of the Adivasis of Bangladesh living on the fringe and to understand why their way of life, culture, tradition, history, and education stand to be extremely valuable for Bangladesh." As stated, a number of writers attend to this objective with varying degrees of skill and acumen. A particularly fascinating, incisive, and informative reading is Niaz Zaman's "Traditions of Backstrap Weaving in Bangladesh". She paints a rich canvas of the art of this traditional form of weaving that continues to be practiced across various indigenous groups "despite the political turmoil and social changes" that have affected them. She also draws attention to the plight that they have to endure in keeping alive their tradition: "The exquisite pieces...(t)oday...are like collectors' items and command a high price but, as often happens, weavers do not have access to markets. Unable to sell these products, they fall back on what is easier." Her solution to this unpleasant conundrum, while rather conceptual, nonetheless, demands attention from the appropriate quarters as a starting point towards a satisfactory middle ground between the imperative of the preservation of a tradition and the practicalities of modern market requirements: "To retain or revive traditional weaving, the right incentive must be given as well as a realization that indigenous weaving is not only a functional product but also a work of art and the preservation of a unique life culture."

Shanjida Khan Ripa, Prokriti Nokrek, Partha Shankar Saha and Khokon Suiten Murmu with Philip Gain provide a kaleidoscopic account of ornaments used, objects of daily life and culture, musical instruments, and alcoholic beverages consumed by the various indigenous peoples in "Selected Flagship Objects of Adivasi Life and Culture". Although people are generally aware of the major ethnic communities, to underscore a point Gain made earlier, Sukhamoy Rabha, Subhash Jengcham, Shanjida Khan Ripa, Selina Hossain, Sabrina Miti Gain, Sabiha Sharmin Shimi, Shakil Sarforaz Rabbi, Raphael Palma, and Tahmina Shafique in "Little-known Ethnic Communities", meticulously document, as the title suggests, the "largely unrecognized, excluded, forgotten, or unknown" separate communities living mostly in the Northwestern and Northeastern regions of the country. Each piece is interesting reading, reinforcing the point made by Brauns and Loffler about the richness and diversity of the indigenous peoples.

Raja Devasish Roy Wangza provides an insider's view, as it were, of the serious issue of the constitutional and political standing of the Adivasis in "State Policy, Constitution and Equal Rights for Indigenous Peoples of Bangladesh". His is more of an information-providing, rather than a critical, essay, although his dissatisfaction with events over the years shows through. Alex Dodson, on the other hand, is an outsider looking in who, in a short, but clear-cut, discussion on "Adivasi Languages", offers this gem: "A language is not simply an object and it is not an artifact. It is not merely a scholarly curiosity, and should not be treated as such. A language is what people make of it. What is prudent is for support to be provided to any community, which desires to preserve its language, however defined."

The very subject matter of the book will dictate that political issues would be brought up. And so they are. Gain, at the outset, gives indication of this direction: "One key message we want to communicate through this book is that the state must recognize the Adivasis, put in place legal framework, and set mechanisms for their safety." He does not mince words when making the accusation that, "The Adivasis in the plains are disadvantaged people and face acute discrimination for being Adivasis." He discusses the disadvantages in relation to identity and recognition, lack of baseline data and under-counting, lack of political protection and security, participation in democratic practices and institutions, alienation from land, forests and commons, and frail institutions. Gain invokes Father R.W. Timm's 1991 writing to explain the Adivasis' plight. Timm had concluded: "The attitude of Bengalis to Adivasis is based on culturally inherited stereotypes of Adivasis as primitive or 'jungly' people, even as headhunters (as indeed some of them were in the past). They don't speak Bangla correctly and their religion and culture is regarded as inferior. They are seen as migratory people of no permanent abode."

There are shortcomings in the book. One has been alluded to. For a work of this size and involving no less than forty seven contributors, the quality of the write ups would more likely than not be uneven. And they are. But some of the other drawbacks have been brought up by Gain himself. Let him take them up: "this book fails to do equal justice to all Adivasi groups, especially to the smaller and merged ones.... the second major deficiency is that not all the profiles demonstrate uniformity and cohesion in organizing and style. Some profiles are based on good research and therefore are well written by world class anthropologist and professional writers, but many are sketchy, done by amateur writers." But those are relatively minor deficiencies when considered in the context of the enormous scope of the book and the wealth of information it provides. For example, it tells us that the number of ethnic communities in Bangladesh could be as high as 90 rather than the 27 given out by the government. And, Survival on the Fringe: Adivasis of Bangladesh, delivers a strong message through its editor: "The majority of the people...need to better understand these people and be bold enough to sacrifice at the personal and community levels. Changes in their attitudes about the people, tolerance and a helping hand can build true partnership and solidarity with the groups that have become lesser citizens due to geographical, religious, historical, and political reasons."

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

For all latest news, follow The Daily Star's Google News channel.

Comments